Born into an artistic family in Australia, Jacob has been living in Italy, on and off, since he was two-years-old. He began his musical training very young and brings these sensibilities to his art. All the music in this episode was composed by Jacob.

Jacob Cartwright, Ascoltare (Listen), 2019

Jacob Cartwright, Resonance, 2019

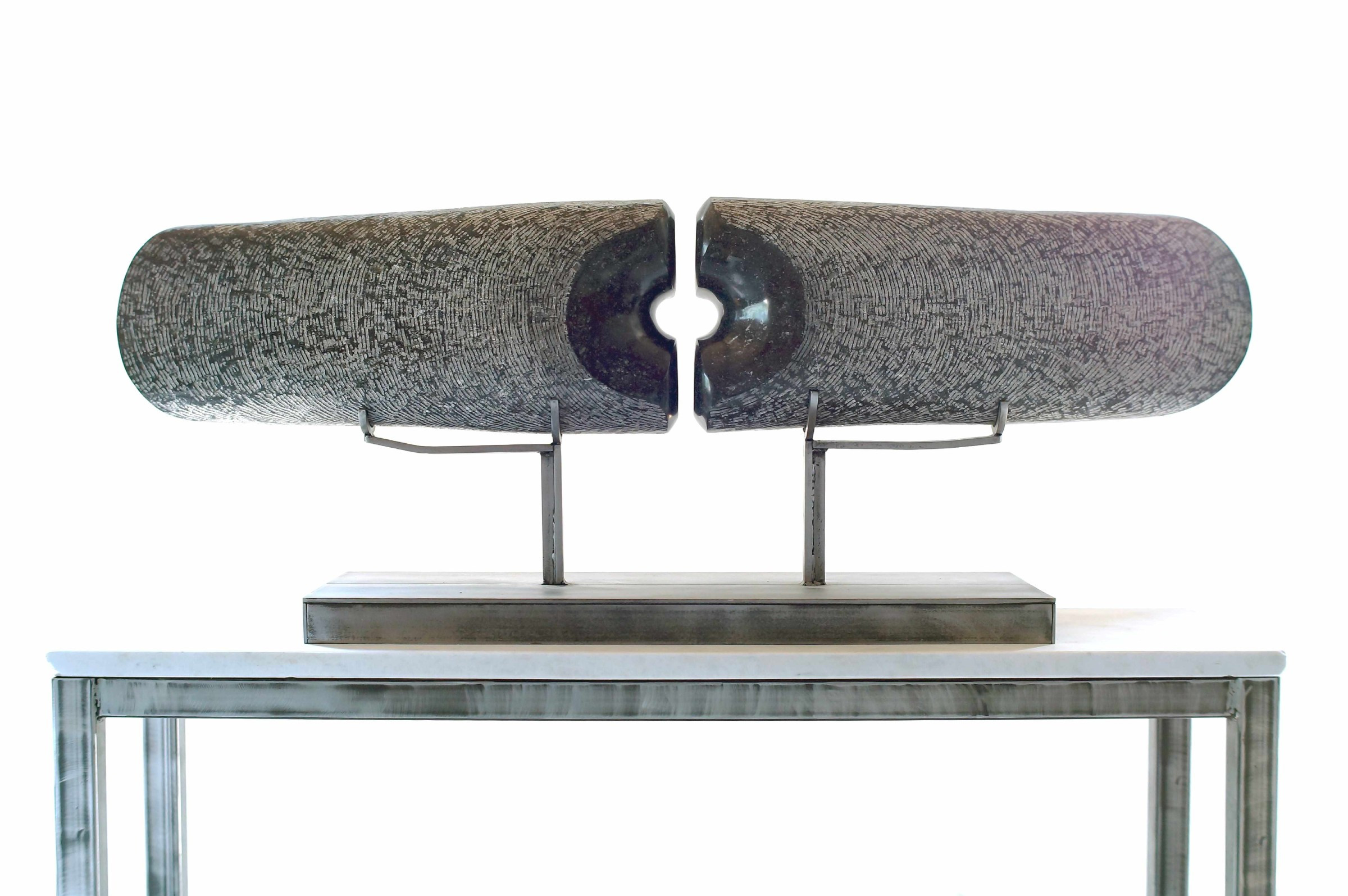

The Embrace series was inspired by a hug Jacob’s wife Jacqueline gave him. He explains that when his wife gave him a hug he saw a certain form. This form became a piece and this piece then developed into a series of work about the embrace. He also feels that his deep links with music played a part in influencing the outcome. He says, ‘It's a beautiful subject matter because an embrace is a paradox: giving and receiving at the same time. It's like two things at once and everything at once’.

Jacob Cartwright, Seabreeze, 2019

Jacob Cartwright, Embrace, 2019

Jacob loves carving wood and working to optimise its fibre and grain, discovering how it might split or break. He describes his love of the textures of wood and explains both the process of burning wood and using the burnt wood with oil to make a patina. Sometimes in making a sculpture he will cover whole sections of wood with nails.

Jacob Cartwright, The space between us, 2019

Jacob's studio showing: Nostro abbraccio (Our embrace) and Full

Jacob usually worked with the aid of machinery but admits that he hasn’t yet made up his mind about whether or not to use a robot in future. When health and safety regulations around dust became an issue, Jacob decided to embrace a change within his studio and reverted to working marble by hand and avoid machinery altogether. He tells us how this meditative way of working influences his life.

Just some of Jacob's hand-tools

Links

instagram.com/jacobcartwrightartist

Referred to in this episode:

He mentions the Cartwright family exhibition at Australia House. We also interviewed Jacob's mother, Shona, and father, Michael.

Something that has recently inspired me a lot, was doing Tai Chi for quite a bit, and that’s working with energies. When you are working with your body and your movement and your energy, you start to visualize that. I remind myself to remain open and to embrace what comes from the day of people I meet, things like that. That to me becomes almost like a geometric, energetic shape. And that’s what I’m sculpting a lot these days, these kind of pretty, sounds a bit new age, but that feeling, those images interpreting what I feel or hear into form.

Sarah Monk:Hi, this is Materially Speaking, where artists tell their stories through the materials they choose. In this series, we’re talking to artists in a community in Northern Italy who carve marble. They’re here not only because of the range of marble, but also to work with the exceptionally skilled artisans. We’re 30 miles north of Pisa and 15 miles south of the Marble mountains Of Carrara, 2 miles inland from the Versilia coastline, whose beaches in summer are packed with colorful umbrellas. We’re near a town called Pietrasanta, nicknamed Little Athens because of its tradition for carving marble.

Sarah Monk:Today, I’m talking to Jake Cartwright, an Australian artist who comes from a family of sculptors who recently had a family show at Australia House in London. As well as being an artist, Jake is also a talented musician and composes for film, dance and theatre. I caught up with him at his studios in La Polveriera , one of the last remaining studios in the centre of Pietrasanta. Behind the large metal gates were a number of workspaces, some indoors, some outside in the yard, under roofing made from corrugated iron. Jacob’s studio is inside, and there’s a deep comfy sofa, a small desk, and a large range of hand tools.

Sarah Monk:His abstract sculptures in wood, marble, and other stone are mounted on stands around us.

Jacob Cartwright:My name is Jacob Lucius Cartwright. I’m Australian. I’ve been living in Italy for the last ten years and I’ve been sculpting here in Pietrasanta, in this studio particularly for the last two years, La Polveriera , but coming to Pietrasanta for a long time.

Sarah Monk:So this series of Embrace, are you doing work in wood? And if so, how do you make those choices?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah. Doing them both, definitely. But more so in marble, this particular series. But at the same time, when I was in Norway, I did sculpt a piece that was definitely a part of this Embrace series. And in fact, has inspired other pieces in Marble when I came back, like this piece I just finished recently in the corner there.

Sarah Monk:Brilliant. I love, I love the Embrace. So I think you’ve said before that the Embrace is as it’s like embracing the future as much as a person, is that?

Jacob Cartwright:That’s right, yeah.

Sarah Monk:So it’s a state of being.

Jacob Cartwright:Yes, that’s correct. Yeah. Yeah, just life in general. Absolutely.

Sarah Monk:So if you don’t mind me, I actually don’t know how old you are, Jake.

Jacob Cartwright:I’m 39… 37. 37 really.

Sarah Monk:So where where were you born?

Jacob Cartwright:I was born in Melbourne, Australia.

Sarah Monk:And your parents were artists? Were your grandparents artists?

Jacob Cartwright:Yes. Yeah. Both of my grandfathers were, are artists. One was, and one still is.

Sarah Monk:What sort of training did you choose?

Jacob Cartwright:I come from the background of music actually, apart from the fact that my whole family is sculptors. When I was nine, I started playing the clarinet and from there went to lots of different arts academies for sound and for composition. That’s my background. So I’ve come back, done the full circle from my parents as sculptors all the way back to being a sculptor again, but via that voyage of sound. So for me, that’s a big influence.

Jacob Cartwright:So that can be emotive descriptions of sound or it can be even to the point that a sculpture might make a sound, so a sound sculpture or sound installations.

Sarah Monk:So what was your movement? You went to normal school?

Jacob Cartwright:I went to the Victorian College of the Arts at 12, which was a music academy on a tertiary campus. And then at 15 went to The States on a scholarship to the Interlochen Arts Academy for composition, writing music. And then went back to the Victorian College of the Arts, but in the tertiary studies at 16 for composition again. And then did a sound engineering course. So I was very much studied in sound.

Jacob Cartwright:But at the same time, my whole family being artists, I was doing that the entire time as well, but not with the same focus as I had for music and composition. But the last ten, fifteen years, I’ve been moving back more and more into the visuals and it’s actually now more weighted towards that than sound.

Sarah Monk:So you left Australia when you were 22?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, 22 I was very much into writing experimental electronic music. And I left because I just finished a long term relationship and I felt like it was the right timing to go back out into the world. Because I’d done quite a bit of travelling earlier in my life, I thought it was a good opportunity to do it on my own.

Sarah Monk:And then where does Italy come into the picture?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, so on the way through to London, I stayed six months in Italy and met some great people. And one of which invited me to Madagascar to do this humanitarian aid job. I was there recording local musicians for the documentary they were putting together about the work they were doing. It was an amazing experience. And I traveled around for a month with Jacqueline, my wife, and that’s how we kind of fell for each other.

Jacob Cartwright:I think I fell for her more than she did. And then the reason why I came back to Italy is because she’s from Italy. Well, she’s actually Cappovedian, but has been living in Italy for the last thirty years. I came back to be with her. That’s my reason for being here actually.

Sarah Monk:That’s lovely. So you come back to the Pietrasanta area. And where do you put yourself to work at that point?

Jacob Cartwright:I have a studio, it’s called La Polveriera, which is actually one of the last remaining large studios in the center of Pietrasanta. It was run by Cervietti, who’s one of the most famous artisans of this area. The work here in this space, there’s eight artists altogether. It’s more of a cooperative.

Sarah Monk:And what’s it mean to you, Polveriera? How does that support your work?

Jacob Cartwright:Apart from the fact that Pietrasanta is the mecca for sculptures, just for the fact that there’s everything you could ever need or need to know about sculpture here. So all of the materials and everything, but the Polveriera itself, it feels great to walk into. I mean, it’s a beautiful place, not for the fact that it’s beautifully arranged or anything, but just for the fact that there’s been creators here for two hundred years or one hundred years at least. I think it leaves a dust behind or some kind of energy. So for me, it really gives me a lot of inspiration. I just feel at home here.

Jacob Cartwright:And then there’s also the people, my colleagues there. It’s a wonderful group of artists and we’re all very supportive of one another. I don’t know if it’s rare, but I feel very lucky at least to have such a supportive network of people, lots of cultural exchange, really good ideas and great discussions and dreams that get thought about when everyone supports one another and their dream is really lovely.

Sarah Monk:And what about the resources of the area?

Jacob Cartwright:Wow, they’re incomparable. I mean, there’s just so much here. There’s the Carrara just around the corner, there’s the Henraux Quarries, just a ten minute drive away. So you have all the marble you could ever need. And not just Italian marble, but marble from all around the world for the fact that there’s such skilled artisans here that marble comes everywhere to be worked upon by these people. So everything you could ever imagine in terms of material is available.

Jacob Cartwright:And then some of the best tool makers are still here. A lot of them are closed but there are still some amazing tool makers so you can find everything you could ever need. And then just more than anything, it’s the I guess the history of Pietrasanta has meant that there’s a beautiful relationship that’s been built between artisans and artists. So you have this immense wealth of information here.

Jacob Cartwright:If you need to find something out, you’ll find out. And you’ll do so by meeting lots of cool people.

Sarah Monk:How do the mountains and the sea and the nature of this bit of Italy inspire your work?

Jacob Cartwright:When I go and sit by the sea or when I go and sit by a river, the rivers are spectacular and these mountains are amazing. It balances me. So I think more than anything it’s about maintaining my capacity to be present and they definitely are influential. The nature around here is spectacular.

Sarah Monk:Do you do shows or do you work towards a body of work?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, definitely work towards a body of work. It’s hard to say chicken or the egg. Sometimes I’ll just be working for the sake of working and following a theme or following something that intrigues me and that I need to explore. At the same time, at the moment I’m planning for an exhibition that’s going to incorporate these pieces that are free, but also more conceptual work. And that’s more of a plan for exhibition and it’s outlining something specific. So both, both ways, definitely.

Sarah Monk:And do you do commissions?

Jacob Cartwright:I do. I do commissions. I find commissions really challenging.

Sarah Monk:Why?

Jacob Cartwright:Why? Well, because often a commission comes from someone else’s inspiration and it’s your interpretation of that. I mean sculpting in the first place, think you’re often in a battle within your mind about trying not to think of an audience by trying to be as honest as you can to yourself. So that’s complicated as it is. Once you add someone else into the mix, then it can become even more so because you actually do have to think of the audience.

Jacob Cartwright:But then again, you have to realise that they’ve chosen you because they trust you as an artist. So there’s all of those things to consider or try not to consider while working. And then again, sometimes people will do something like ask a piece to be done in another material. And that means you’re copying yourself. And that’s really interesting too, because while you start looking at the piece objectively and it almost doesn’t become yours anymore and you’re copying it.

Jacob Cartwright:And you’re trying to find the same magic that you felt while doing it in a free process. And you’ll start to realise that there’s all these really intricate things that you didn’t even realise you’d done and try and catch up with that again is interesting. There is one way of copying a piece which is using a very technical method, which I just refuse to do because it’s too technical. So it’s all by eye.

Sarah Monk:Is that points or robot?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, they’re all robot or points. At the moment I’m not really, haven’t even experimented with robot or not. And I can’t say for sure that it’s something that I don’t know what I feel about the robot yet. I have some ideas of how to use it which could be fun. But the pointing thing is it’s very laborious and it’s a technician’s job. I’m not a technician.

Sarah Monk:I’m back with Jacob Cartwright in his studios. What are you working on today? We’re outside.

Jacob Cartwright:Well, it’s a beautiful piece of stone. It’s a Carrara ordinario. I’m working on it by hand, the old school methods like Michelangelo used to do. So no power tools at all on this piece. The piece is I guess the object is turning into something that seems a bit like a a reclining figure, female reclining figure, but could also be a bird.

Sarah Monk:And why have you started working in hand again?

Jacob Cartwright:Just recently there’s been a whole lot of health and safety regulation things, so there’s been a lot of studios closing down in Pietrasanta because of the big fines in regards to how we’re looking after our dust. So I’ve stopped working with any kind of machines that create dust. I just thought I’d roll with the punch, and start sculpting by hand. I had a good think about it and it’s almost like a moment of inspiration. Why not just learn to sculpt by hand so that I can work almost as fast as I would with big tools?

Sarah Monk:It’s a funny kind of end to a technology trajectory we were talking about earlier last time we met.

Jacob Cartwright:Things change, I’m embracing it. For me it’s become much more meditative the process, I’m finding it is actually influencing all parts of my life just by being able to be peaceful, for 8 hours a day. Yeah, it’s beautiful actually.

Sarah Monk:I was gonna ask you how you go about choosing a bit of stone or whether a piece of stone chooses you.

Jacob Cartwright:Sometimes it could be that a piece of stone talks to me.

Sarah Monk:How does that feel?

Jacob Cartwright:I guess the material itself gives me inspiration for a piece. Or it’s just this beautiful looking piece of stone and I want to get my hands into it and get dirty, you know? But then again, there’ll be sometimes a concept or perhaps development from a past piece, and I want to experiment with the form that I’d found, and it requires something. I think some forms require some different kinds of material, like I mean, a very clean, controlled form with beautiful lines could often need something like a white statuario or something like this. But then again, a form that feels more, I don’t know, earthy and is expressing something ancient, then perhaps something more like a Marquina from Spain would be more appropriate because it’s got all these beautiful fractures and different discolorations that kind of speak more of the earth.

Sarah Monk:I don’t know that. What’s it called Marquin?

Jacob Cartwright:Marquinha or Marquina. Depends who you speak to, but they’re different names. But it’s black and it has a lot of fossils in it. So white fossils, usually of shells. And then it also has white veins running through that as well.

Jacob Cartwright:And sometimes small fissures and cracks that don’t affect the quality of the stone, but just give it that kind of rustic feeling, I don’t know, more earthy. It’s a more earthy feeling.

Sarah Monk:That’s really interesting. So do you tend to, if it’s not a commission, if you’re making pieces, do you make them in something else and then carve them in stone? Do you start straight on the stone?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, I work directly. And sometimes I’ll start with something in my mind’s eye. And occasionally that piece that I’ve seen in my mind’s eye will come out as I’d thought of it being in the first place. But often the process of actually working on a piece, you discover things that you hadn’t anticipated. There could be problems with the idea that don’t translate into a three-dimensional form as well as you thought.

Jacob Cartwright:Or it could be that you get this beautiful opportunity to express something new that you would have never found. And if I didn’t have that flexibility or freedom, then I wouldn’t find these beautiful new directions that in fact usually inspire the next piece.

Sarah Monk:What about other materials?

Jacob Cartwright:I love wood. It’s incredible how it gives you a different process. Yeah. The material definitely, especially if you’re working in a direct way, the material really counts for something in terms of how you create and what forms come from it. Because wood has got an obvious grain to it, They’re fibres and you have to, you don’t have to, but it’s fun to work with those and becomes more fluid if you work with them and understand how things can split or break. And it’s much faster than stone. It requires a different kind of energy.

Jacob Cartwright:Because stone is so demanding of time and focus and physicality. Wood is like that to a much lesser degree and it can be much faster and therefore more fluid and because of that different forms come from it. For me anyway. Wood’s a beautiful material.

Jacob Cartwright:Love it. And I also like to burn it and cover parts with nails. There’s all these different textures. Wood’s beautiful for texture, that’s for certain.

Sarah Monk:So can you talk through a little bit this series you showed me you did in Norway?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, sure. I got invited to this symposium. It’s a biannual symposium. It’s been going for twenty years. And it’s been run by an amazing man who more or less came to this area, Pietrasanta in Carrara, fell in love with the energy here and wanted to bring that home somehow.

Jacob Cartwright:And he’s a sculptor himself. So he started this symposium. So there’s been artists coming from this part of the world to Norway, to this place called Oz, which is just near Bergen. Yeah, and it was an amazing experience. I love Norway. Oh my gosh, Norway is visually spectacular. So we were right on the coast on the fjords.

Jacob Cartwright:But I was invited there because this year they had decided to diversify the medium. So this year, the first time, they were working with wood. So I was asked to come and work with wood.

Jacob Cartwright:And we had these big huge blocks, I had the chainsaws and everything going and working like crazy. But I managed to get two big pieces made there. And inspired by this piece, which I did two years ago, And it’s been sitting there. It’s a beautiful piece. And I’ve just been wondering what is the next extension of that?

Jacob Cartwright:What are the new pieces? And so did two pieces related to that.

Sarah Monk:So can you describe them? Because we haven’t got a picture.

Jacob Cartwright:How can I describe? Well, the piece that it’s inspired by the main, like the roots of this series is a piece which is it’s a big trunk that has been carved as a hole that goes straight through the trunk. It’s almost like a vortex, this hole. And to me, it represents our place in the universe. And it also looks almost like a womb because it’s not a complete circle, it’s divided at one end, which almost looks like the umbilical cord or something like that.

Jacob Cartwright:So for me, it kind of represents our natural state of comfort in our world, almost like the way we felt when we’re in the womb. A lot of my work actually has something to do with how we relate to our life or my philosophy at the moment of how to live. And that was what that was about.

Jacob Cartwright:The other pieces that I did there were variations on that theme. One is linking the two themes that I’m working on at the moment. So there was that symbology of the womb and feeling at one with our surroundings. And then also the embrace, the resonance that comes from your person when you’re open and receiving. So it’s almost like two arms, but these arms are almost like large dishes or something. Does that make sense?

Sarah Monk:It does. And then the coloring on them, you said you burnt them. How did the burning process come about?

Jacob Cartwright:I think I just wanted to experiment with colours. You know, I at one point was looking into stains and how stains work, and I wanted a dark piece. So I tried burning it. And it was amazing what came from that because then you experiment with these things. And I started, once I burnt it or charred it with a blowtorch, I then got the oils in and smudged around all the charcoal.

Jacob Cartwright:And then I realized that the charcoal was becoming almost like an oil paint in itself, you know? And then what that did is it softened all of the textures because I often leave rough chisel marks because I love that texture. And then burning that softened all of those off. And then it also takes away the the softest material in between the fibers. So you get these beautiful grains that become more prominent because the softer wood deteriorates and hardwood remains.

Jacob Cartwright:And that’s actually a process that has been happening for thousands of years. The oldest wooden structure still standing is 1,400 years old. And it’s a temple in Japan. That is the process that they were using at that time. Think they still do.

Sarah Monk:Or burning it and

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, would burn it and then they would oil it.

Sarah Monk:Wow. And what about choices of wood and supply of wood? Presumably in Norway, you got pine?

Jacob Cartwright:Yeah, in Norway, we had a type of pine when it was laminated. Wood’s interesting because I mean, you can use a big trunk of a tree, but what will often happen is that it will move. So you’ll get cracking and opening and closing and depending on the temperature and humidity. But if it’s laminated wood, so wood that’s been sliced and then stuck back together, then that prevents all of that. So in Norway, we were given these huge blocks of laminated pine and fir.

Sarah Monk:How long does wood last or when do you start getting problems?

Jacob Cartwright:That’s something that collectors need to decide about how they go about looking after a work. It’s probably more advised to have somebody look after pieces. For example, marble, if it’s outside, it should be looked after once a year. If it’s inside, then it’s much less than that. And that would be the same case for wood.

Jacob Cartwright:Mean, going outside, you’re going to have a limited lifespan. If it’s burnt, then it can last a lot longer. If I was to show in Asia, somewhere like Hong Kong, for example, they’re much more inclined to be interested in stone than in wood, just for the fact that humidity in places like that can be more problematic for a material like wood.

Sarah Monk:How does the context of where the piece is going to live affect how you create it? Do you know where these pieces are going to go?

Jacob Cartwright:That’s a beautiful question. I like the fact that you said where it’s going to live, because it’s true. Think a piece is not really finished until it’s got a home, you know? And it’s living with people. But how does it affect the way?

Jacob Cartwright:It depends. I mean, if it is commission, then of course it affects the way I’m thinking about it. I think sometimes it becomes apparent while I’m making it where a piece like this would be beautifully set, you know? But apart from that, I don’t really let that affect the creative process too much.

Sarah Monk:What is your opinion about us using resources, marble and wood, and the discussions about the finiteness of the quarries?

Jacob Cartwright:I’m in two minds about these things. I mean, I I think it’s a real shame that these quarries are being used mostly for large scale architectural projects like malls and things. And they’ve used just because it’s in at the moment, to use something like a statuario, which is for hundreds of years been reserved for figurative sculpture because it’s the only stone that really allows a sculptor to represent somebody and not be worried about a blemish in the stone affecting the way that the face looks or the expression or something like that. And it’s really hard to come by because you have these huge walls of marble and it’s not like there’s one quarry that has statuario. There’s a massive wall of white marble with veining going through the entire thing or clouding and different densities and things like that.

Jacob Cartwright:And there’s these tiny pockets in this massive wall of pure white of a certain density. And that’s Statuario. And they cut those little blocks out, could be a very small to medium, it’s very difficult to get large blocks of it. And it was, until now, reserved just for the sculptors. But now it’s being sliced up, sliced and diced and sent off to put in bathrooms and stuff.

Jacob Cartwright:And that’s very limited resource. So I just think it needs to be managed a bit better. I mean, I’m not a quarry owner, but from my perspective, what I see. I think using resources to be turned into beautiful objects that remind people about life or the beauty around us, then I think that’s a valid use of a limited resource.

Sarah Monk:So what would you say influences your work? What inspires you as an artist?

Jacob Cartwright:It’s a good question. Because a lot of things inspire me. Seems like at the moment the thing that’s inspiring me most is my approach to life. My wife Jacqueline gave me a hug a few months ago. And I think because of my history with music when I was improvising I would see what I would hear.

Jacob Cartwright:I’d hear something and I’d see it in my mind. It has three dimensions and colors and things. And I think that translates, I’ve noticed that if you’re aware of it, you can pick up these images from other things. When my wife gave me a hug, I saw a certain form and that has turned into a piece now. And it is becoming a series of work about the embrace and the embrace is a paradox, you know.

Jacob Cartwright:You’re giving and receiving at the same time. It’s like two things at once and everything at once.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to Jacob Cartwright. You can see his work on his website at jacobcartwright.com, and follow him on Instagram @JacobCartwrightartist. For photographs of all the work discussed in this series, check out our Instagram or our website, materiallyspeaking.com. And don’t forget to join the mailing list to hear about upcoming episodes.