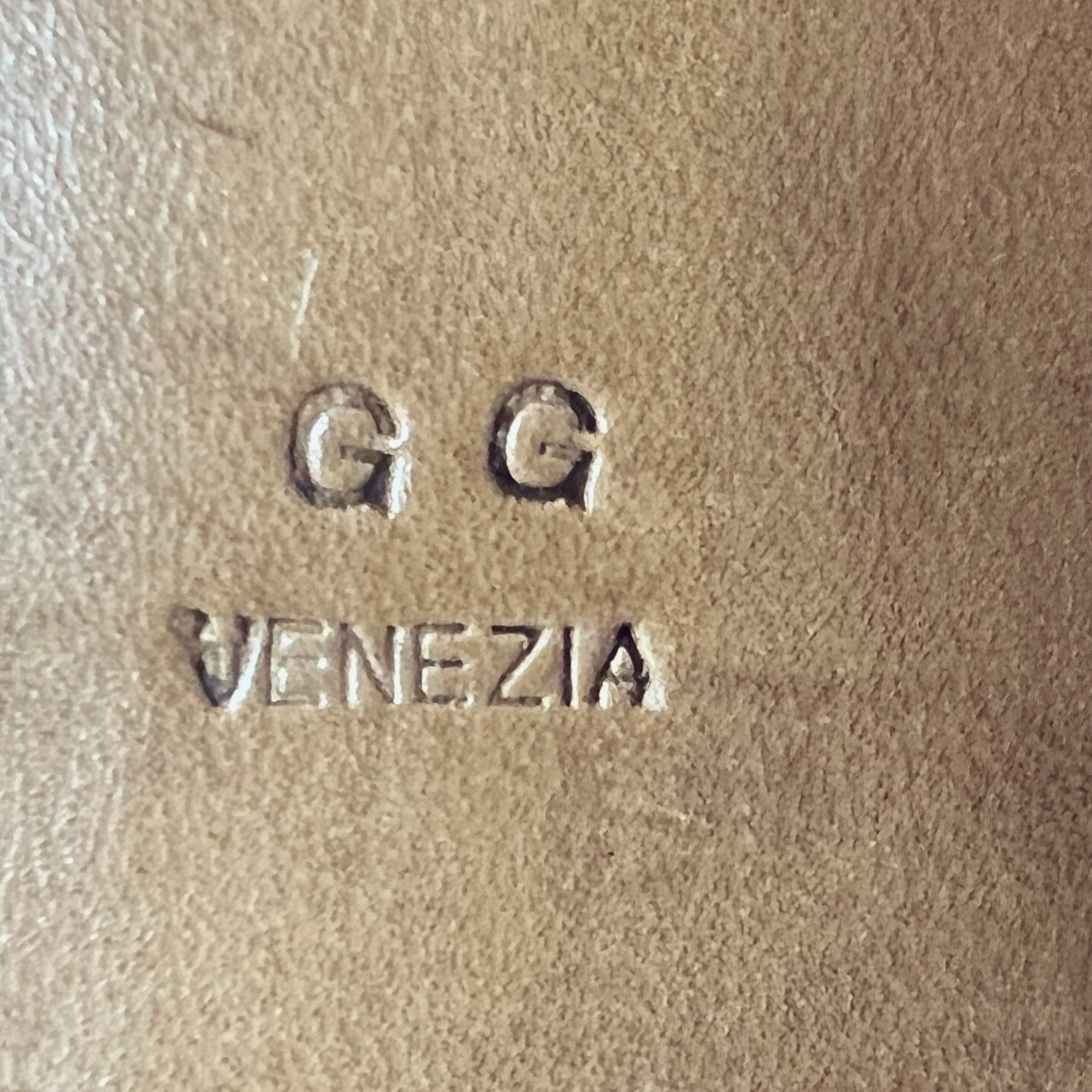

Gabriele Gmeiner, 2022

In this, the second of our Venice series, Mike Axinn and I met Austrian born shoemaker Gabriele Gmeiner who makes high quality made-to-measure shoes in her workshop at Campiello del Sol. She speaks of her craft, her journey from Austria and why she chose Venice.

As we turned into Gabriele’s courtyard we found her sitting at a large wooden desk by her shop window, wearing a work apron, and smiling. A shoe was jammed between her knees as she filed the base of it. In front of her were a wide selection of hammers, tapes, knives and glues.

Leather ribbons were stapled on the walls and dozens of wooden handled tools were slotted inside their curves. Above her head, suspended from the ceiling, was a forest of wooden shoe lasts.

Gabriele studied at Cordwainers College in London, and in Paris at the Centre Formation Technologique Grégoire for saddlery. She honed her skills over ten years working throughout Europe before she came to Italy and made her home in Venice.

Every July Gabriele directs the shoemaking workshop of the Salzburg Festival making shoes to measure for opera singers and actors to support their performances.

She talks us through the process of creating the perfect shoe: from measuring the client, crafting the shoe, to the final fitting. She keeps the original last and also repairs shoes, ensuring they have a long life, and that their beauty grows with wear.

Gabriele talks about sustainability and explains how she tries to source sustainable cowhides from the food industry.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound recording, edit/design: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Flying Colours 3703/4, Christopher Slaski

Gabriele Gmeiner (00:00):

I think the Venetians, they need such realities and I also need Venice. I mean, it’s not metropolitan like London or Paris where you have the customers living there. Not being a metropole, the living conditions in Venice are much better than they would be in London or Paris. It’s much easier to live in Venice, but still I can work with the same clientele and especially in Venice. I mean, it’s the walking city. You don’t buy tires for the car, but you buy good shoes because you have to walk. I think the city is made to measure to the humans for me.

Sarah Monk (01:08):

Hi, this is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. In the second of our Venice series, Mike Axon and I are meeting Austrian-born shoemaker Gabrielle Gmeiner. As we set off a trolley rumbles by bearing bread and then another carrying bottles. A man trudges over with a cart to fetch some crates of vegetables from a passing boat and wheel them back to his restaurant. This is a city on foot. As we make the last tight turn into Gabrielle’s courtyard, we find her sitting at a large wooden desk in her shop window wearing a work apron and smiling. A shoe is jammed between her knees as she files the base of it. In front of her are a wide selection of hammers, tapes, knives and glues. Leather ribbons are stapled on the walls with dozens of wooden handle tools slotted inside their curves. Suspended above her head is a forest of wooden shoe lasts.

(02:18):

Can I ask you to tell us your name and what you do?

Gabriele Gmeiner (02:21):

My name is Gabrielle Gmeiner and I am a shoemaker. I was born in Austria in a small, small city called Bregenz, which is on the lake of Constance in the west of Austria, close to the Swiss border.

Sarah Monk (02:40):

Was shoemaking something that your family did?

Gabriele Gmeiner (02:41):

Actually, there was a grand granduncle, but I’ve never met him when he was alive. When he died, the relatives, they said to my father, "Your daughter, isn’t you making shoes? Wouldn’t she be interested in having his tools and certain things?" I went to see, and he was actually years ago a good shoemaker. Then of course he ended up in repairing shoes like everybody did in the ’60s, ’70s. Nobody wanted to have made handmade shoes. I have this working bench here and I found really interesting old materials, handmade nails and especially for shoes, nice tools and it was a nice heritage.

Sarah Monk (03:37):

How about your childhood and your education? What sort of things were you interested in then?

Gabriele Gmeiner (03:42):

It was a free childhood in nature, it’s countryside there and I got interested in school and art and making sculptures, which I also did during the school time. I also was orientated in languages, so that already prepared my way then to move freely in the whole of Europe.

Sarah Monk (04:09):

How did the decision come about to make shoes?

Gabriele Gmeiner (04:13):

I was very much into arts and I was doing sculptures and clay and any kind of materials. I was experimenting and my thoughts were, "No one of my family has been an artist and doing arts just for the art sake," so I decided to make something applied, some applied art, which is [foreign language 00:04:39]. It’s a halfway through and I built up a whole philosophy about what is the shoe, how does the shoe influence on the human being? If I create a sculpture for the feet, how does it influence in the movement and wellbeing? What is the shoe today? It’s the basement of our modern living. It was very complex and then actually I said, "Oh, I want to make portraits, very detailed, for the persons and I will work for …" and yeah, that was the initial idea.

Sarah Monk (05:22):

How old were you when you came up with this philosophy of shoemaking?

Gabriele Gmeiner (05:25):

I was about … when was I? 18, something like that. Then I already started looking for a place where to learn the techniques and I first went to Vienna to the old master shoemakers and they were all dusty and rigid actually and said, "Oh no, no, it’s no trade for ladies," and I said, "Oh, dear." I was desperate. There was a lady from London doing costume design, Nikki Gillibrand and she said, "Oh, there is a school in London. You should have a look there. A school specialized in shoe making." That’s how I started really to get into the craft.

Sarah Monk (06:12):

You came to London when?

Gabriele Gmeiner (06:15):

I was 19. ‘91.

Sarah Monk (06:25):

What was the school?

(06:25):

That was the Cordwainers College and that was in Hackney at the time and I got inscribed in this technical shoemaking course. How was it? Two years course. It was great because I had a really nice all overview of shoe making, but then as the school was rather specialized in preparing the students for the industrial-

Gabriele Gmeiner (06:57):

The commercial side.

Sarah Monk (06:59):

Yeah, industrial production of shoes, I tried to find my way in what I was looking for in the hand making and the very personal shoe making. I found also the companies, the workshops in London making such shoes, of course. I had the chance to work on all the details. Making shoes, really, it’s composed by different professions. There is the last make, there is the pattern make, there is the clicker. The clicker, very special term, the cutting the leather, and then there is the upper sewer. I could really experiment with it all and the good thing at school is that you can make errors, you can experiment.

Mike Axinn (07:48):

If there is all these different professions within shoe making, do you do all of them?

Gabriele Gmeiner (07:53):

Yeah. That’s a quite holistic thing, but that’s part of me because every step makes part of creating I think. Making the last, I’m already thinking of how many layers I have to add, how can I add the layers? What’s coming out at the end. Each step influences on the shape, the outcome of the shoe.

Sarah Monk (08:22):

Wow. What was the step after Cordwainers?

Gabriele Gmeiner (08:26):

After Cordwainers, I did some work experiences. I went to John Lobb as well. I did some months there, I did some holidays, substitutions, and I went to the home workers. John Lobb, they work with the people that have their own workshop and they would send the material and the work to do to them and they would send it back. All the people working for John Lobb, they’re not all sitting at Sun James Street. I went to one of them and I was in Todmorden up north, near Manchester and I could realize a shoe with their help and I did these kind of work experiences.

Sarah Monk (09:15):

We’re sitting in Venice. How did you get to be here?

Gabriele Gmeiner (09:19):

I was traveling, about to learn, the 10 years of learning process. There was London then I was in Paris as well. There was a school specializing in hand sewing directly related to Hermes, the saddlery sewing. In between that, I also realized autonomously private arts projects. Just to give you a short description, the first one was coming back from Vienna, I went to the place I’m coming from. It was a very countryside place and apparently not very much culture. I was trying to make a research about still the old crafts in the region and the materials they used, the farmers, to create shoes or anything else, and I used these materials to create four pairs of shoes, which were portraits of personalities from literature.

Mike Axinn (10:30):

Another question, how would you describe your aesthetic, your design, your philosophy of design?

Gabriele Gmeiner (10:37):

It’s very, very classic and I think it varies really from person to person. I’m trying to get also the person’s wishes. I mean, what they want to have the shoes for, but the aesthetic in itself, I think it’s all about proportions. It’s all about now if a customer has a difficult foot, so many of us, we have difficult feet, I want to portray this foot to gain the measurements, but have a really nice aesthetic shoe coming out. That varies really from foot to foot. It’s all about proportions. My creativity now, it’s not that much anymore about experimenting materials. It’s about finding the right proportions in a thicknesses, distance, curves. One millimeter here or one there. I mean, it’s such a small object, a shoe, far smaller than a house would be. One millimeter more or less, it changes the aesthetic. It’s all about that, but it’s very classic.

Sarah Monk (11:52):

Great. I think that takes us on beautifully to the process of making a shoe. Can you tell us what happens from someone expressing an interest in having a pair of your shoes?

Gabriele Gmeiner (12:05):

Well, I always start with the measurements of course, and just taking the measurements and talking about the foot, it takes about one hour. The person would come here and I take the measurements when the person is seated and there is just a part of the pressure on the foot and then standing as well with the whole of the pressure, so that sometimes changes a lot the measurements, sometimes it does not. That depends on the consistency of the muscles, the tenants of the foot. We would talk about sensibilities of the feet or I would check all the shape of the foot and the arch and then we would talk about what the customer expects of the outcome. If he wants a very elegant shoe, if he wants an elegant but everyday shoe or if he wants a rather casual shoes.

(13:08):

I’m trying to get the person to collaborate to get involved because it’s not a ready made product, see it, take it, go away with it. The more I can get the person to work with me, the more happier I am really. Once we stabilized all that information, I would start making the last. Here I get back to my regions in making sculptures, I would order a rough cut of the last, which has the basic measurements included, and then I would work on it to get to the measurements of the person.

Sarah Monk (13:46):

Can I just ask you to explain what a last is?

Gabriele Gmeiner (13:49):

The last a wooden shape, which is the positive representation of the foot, and I would make the negative, I think. Or what is it? I would build the shoe around the last and then the last is taken out and it represents the foot actually, but it’s not the foot.

Sarah Monk (14:13):

These are lasts, are they?

Gabriele Gmeiner (14:14):

Yeah, they’re hanging above me.

Sarah Monk (14:20):

What are they made of?

Gabriele Gmeiner (14:22):

Of beechwood. It has to be hardwood because we are beating a lot on it to force the leather into its shape. We are also helping with the hammering.

Mike Axinn (14:33):

I love that you talked about it as a negative and a positive almost like photography.

Gabriele Gmeiner (14:38):

Yeah, it is really. The last, they stay with me as the negative stay with the photographer. Sometimes people ask, "Oh, well can we take the shoe lasts with us?" I said, "No, no, no, that is the Il diritto d’autore." It stays with me as the negative stays with the photo."

Mike Axinn (14:57):

Is that the intellectual property?

Gabriele Gmeiner (14:58):

Yeah.

Sarah Monk (14:59):

Okay. So we have a last, I’ve come in and I’ve been measured for a last, what happens next? Can I ask you to explain the materials as we go?

Gabriele Gmeiner (15:09):

The next step would be that I make a test pair. It’s a proper shoe really. It’s made with second choice materials and sometimes also recycled materials, but it’s a working shoe, I say, because the customer has to wear it to find out if everything is as it should be. That’s for new customers. The risk of having errors in the making of the last is about 20%, sometimes more. Doing this gives the guarantee that we get to 100% really nice fit.

Sarah Monk (15:47):

When you say second choice materials, can you give us some examples?

Gabriele Gmeiner (15:53):

Talking about the skin of a box calf. The whole skin of the box calf, I can gain two, sometimes three, pair of first choice material, which I would cut out on the back of the animal. You’re going towards the belly and the neck. The fibers of the leather get looser because on the animal there is more movement on the belly and also on the neck and more fat inclusions among the fibers. That loosens the structure. For the first choice material, I want to have a really tight structure that doesn’t move too much because I would pull it then on the last and it should not move anymore once it’s on there, because the leather, it doesn’t have to give way to the foot because I have already the last made in the right measurement so it shouldn’t change anymore.

Sarah Monk (16:56):

Where do you source your leathers?

Gabriele Gmeiner (16:57):

The box calf leather I get from France, there is a wholesaler in Milan I contact for. Then the sole leather, I actually changed quite recently. I found this very near tannery. It’s in the area of Pordenone, Porcia, it’s Presot and it’s a traditional company, but there are two brothers and young woman conducting the company and it’s a very nice, sustainable way of looking at this archaic product really. They have winning prizes about no waste. They have a whole recycling of the water, making their own energy for the machines. It’s a all natural product and they have workers from other continents, from Africa. Having a proper contract, they have the chance to have their own garden cultivating vegetables and having chicken for the accent. It’s very, very up to date, this company. I think it’s very sensitive the way they bring it in these times. I got this and it’s really good leather and that’s for the soles and for the reinforcement.

(18:33):

Then special leathers I get … like the cordovan leather, there is this company almost in the city of Chicago producing horse leather and it’s a very special way of treatment because they would color it still by hand. It’s a craft process there and they work in waxes and oils and it’s a quite beautiful product. It’s the luxury of today as the customers, they do not seek any alligators anymore or raptors in general. If they want to do something special, which costs a little more, they would choose a cordovan leather. It’s got a very beautiful shine as it is like a suede leather, even though it doesn’t look like suede because it’s flat and shiny, but the structure is … how you turn it, the light reflects differently so you have a very nice reflecting game on the color that makes it so beautiful.

Sarah Monk (19:49):

Can you tell us about the technical process then of making?

Gabriele Gmeiner (19:54):

Well the test pair, it’s fairly quickly done. It’s just stuck on sole and you’ve got a cork heel, but then the definite pair, it’s all sculpted on the last. We prepare the insole, that’s the sole touching the foot. We have to cut out a kind of wall through which you can later sew on the welds and connect like this the upper with the insole. I have to decide the position of the foot. If I give some more width on the outside to sustain the foot to bring it into better position or other things, or if I want to reinforce the length arch and already this is very personal. Then I would make the patterns. We cut materials, sew it together, quite old machines, but perfectly working machines, they’re still working with pedaling. Then I would pull the upper. I have the upper, which is made with the outer leather and the lining letter, and then we prepare the reinforcement, the back of the shoe and the front of the shoe shoot a toe. They’re always very stiff.

(21:30):

We prepare these, we cut them out from the sole leather and we make them thinner. We skive them with a clicking knife or with a skiving knife actually, and all these materials now work in wet condition. Humid. The leather normally stiff. It gets soft when it’s humid. Then I would pull it over with the lasting pincers and as I said before, I have to pull to the maximum extension. It must not move anymore. I’ll fix it with nails and I would replace the nails with the seam of the weld.

(22:15):

The weld is a thin, long piece of leather, always talking about the thick, the sole leather. That makes a frame around the shoe. I had the little wall already made, the insole, the lining, the reinforcement, the upper and the weld. That’s the shoe as it will stay for a very long time that the person wants to wear it. The sole can be replaced as it needs to be. Once the customer has a hole in the sole, the shoe comes back to me, I will put the last inside the shoe again and so the sole through the same holes again. The shoe’s getting new. Actually is getting more and more beautiful wearing it and having a part in a … and, of course, I forgot to talk about the heel.

(23:17):

The heel is made with different layers of the sole leather still, attaching each layer with a …. there’s a vegetable glue and little wooden tacks. We would make the hole first and then place the wooden tack inside. Also here, it’s still sculpting really. Especially making a lady’s heel. A lady’s heel is not just a straight heel, but you have a nice curve and everything. That’s about the process. In the end, we have to take off the last and give space to the foot and once the foot gets into it, it creates a kind of vacuum. Really. It’s true, it’s true. Customer is always surprised when it happens.

Sarah Monk (24:14):

It’s beautiful. That must be a very satisfying moment. Fabulous.

Mike Axinn (24:21):

That means you’ve done it perfectly.

Gabriele Gmeiner (24:24):

Yeah, definitely.

Sarah Monk (24:29):

What sort of time does it take? I’m sure they vary, but what sort of timing for a pair?

Gabriele Gmeiner (24:34):

I give an average amount of time of about 80 hours, about two weeks of time.

Sarah Monk (24:39):

Do you make your own shoes?

Gabriele Gmeiner (24:40):

I do, I do. That was a kind of commitment since I have my own workshop. So since 20 years I have to wear my own shoes.

Sarah Monk (24:50):

And your family?

Gabriele Gmeiner (24:51):

My husband, he has shoes made by me. I was trying to make shoes for my little boy and at a certain time it didn’t work anymore. I think children-

Sarah Monk (25:07):

They grow very fast, don’t they?

Gabriele Gmeiner (25:07):

Yeah. Also, they have other needs really. I did nice pair of kind of sandals for him and he was making a short sprint of a couple of meters and stopping and it didn’t work. He said, "No, mama, this doesn’t work. They’re not sporty enough." I think they need a very soft and rubber sole rather than a leather construction, I think. That’s fair enough. One day he would want a pair of shoes maybe, being bigger.

Mike Axinn (25:41):

I wanted to just come back to the idea of Venice. How did you end up here and what does it mean that you are here? What’s the significance of you being in Venice with your profession?

Gabriele Gmeiner (25:52):

I was working for a shoemaker and then I went away and came back because I wanted to make an exhibition in his workshop. I have another project in Japan realized and that was the moment that he wanted to get rid of his workshop. He asked me, "Do you want to take over? There is another person interested, why don’t you do it together?" I said, "Wow. I don’t know. I think about it," and actually we found out that the other person, we would have different ideas and it wouldn’t work. But in this time I was helping him as well to get to his orders and this time I found this, my workshop, it was vacant and I could rent it and I said, "Why not Venice?" I think it was quite interesting. I never said, "Oh, one day I want to make be shoemaker in Venice."

(26:49):

No, it happened to be because also many friends of mine, Venetians, they wanted this to happen and I think I would’ve never done it on my own, just one person. It’s not a singular construction, the whole thing. Everybody was kind of helping and they wanted it to happen and so I did and I didn’t expect anything. Then I found myself in the workshop. I said, "Okay, let’s do it here." I think the Venetians, they need such realities and I also need Venice. I mean, it’s not metropolitan like London or Paris where you have the customers living there. I am working with tourism, working for people coming from abroad. I think it’s a very nice solution, really. Not being a metropole, the living conditions in Venice are much better than they would be in London or Paris. It’s much easier to live in Venice, but still I can work with the same clientele.

(28:04):

Especially in Venice. I mean, that’s the walking city. You don’t buy tires for the car, but you buy good shoes because you have to walk. I think the city is made to measure to the humans. For me, it made the same noise kind of.

Mike Axinn (28:24):

Are there other shoemakers in Venice?

Gabriele Gmeiner (28:26):

There are, yeah. We are three ladies. Three ladies making shoes. Each of us has their own ideas and very nice products. It’s still a lot, I think being … Anyway, nowadays it’s a very small city, but still having three hand making shoemakers, it’s quite exceptional.

Sarah Monk (28:46):

But you’ve obviously got a lot of heart for sharing your skills. Do you share the skills in other ways?

Gabriele Gmeiner (28:54):

All the time, really. I always have young people working with me. Trainees staying more or less. Recently I have exchanges from Erasmus, people coming from Slovenia, Austria, France as well. I’ve always had people working with me except of the pandemic. Year one, I didn’t have anybody. Then I’m teaching different teaching experiences and various universities. Latest it was in Venice University, they have the fashion department, shoe and accessories workshop. I think it’s great.

Sarah Monk (29:41):

I’m curious because shoes have become such potent symbols recently with refugees and sometimes protests.

Gabriele Gmeiner (29:51):

I quite liked … I went to Rwanda once, I had workshop there as well, teaching to European students in Rwanda, but with Rwandan craftsman. I liked it because these African countries, they are flooded with Chinese industrial products. The common shoes there would be the plastic sandals, but the beauty there is that they recycle the plastics, they would repair them and they make the most beautiful things with them. I mean actually for our times, these products are not repairable. You use them to throw them away, but they would care for them as we do here for a made to measure shoe almost. They really get the best out of it and for the longest possible.

Sarah Monk (30:50):

Have you made a pair of shoes for someone and recognized how important to them it was?

Gabriele Gmeiner (30:59):

Yes, of course. It happened several times to me. I’m also working for the Salzburg Festival and they make made to measure dresses, hat, wigs, and shoes. I’m going there every year in the months of July and we make made to measure shoes for the solo singers mainly, but also for exceptional productions. There I could tell that they have very particular needs. They have to feel first. They have to feel very well in their shoes and sometimes exactly this fundament is so important. Once I had this very small lady, I don’t even remember her name, she was a great singer. She had a little difficult feet. But anyway, she was working very hard with me to get it right and then she would plant her feet on the stage and push out this enormous voice from this little lady. It was so important for her to have this earth link or earth link. It’s not earth, but it’s a stage link with the shoes.

(32:12):

If this wouldn’t be right, she wouldn’t be able to concentrate and give her best really. It was especially for her, and also for others, very important. That’s why there they still offer this service of made to measure shoes at the Salzburg Festival. Also, the sustain of the holding of the feet. There was another thing, actually. She wanted it tighter than I expected it to make. I would’ve given her more freedom, but she wanted it tighter, tighter, tighter, tighter. Again, this tightness on her feet and she was bringing out her best. I’m talking about two different people, so it’s very important for these personalities, singers to have a particular footwear.

Mike Axinn (33:06):

That’s amazing. Just to think. Did you watch their performances?

Gabriele Gmeiner (33:12):

I do, yeah. I do. I have to. I very luckily have to. It’s the general rehearsal we watch. So all the people working for the workshop, they have to see it. I think it’s very important to see.

Mike Axinn (33:29):

We recorded some sounds of Venice and we recorded the footsteps of people going over the bridges and I noticed no women were wearing heels. There was no heel and heels make a nice sound, so I wanted to get some, but no heels.

Gabriele Gmeiner (33:45):

Well, yeah, walking nicely in Venice with the heels, you have these stones and you get in between and you have the many bridges. It’s not fun. Ladies going for a cocktail meeting, they would bring their high heels in the bag and would just change them just before entering. But then there is a little anecdote. I’m living around the corner here and my landlord, he was a Barron, a Noble, and we were twice invited in his home and he was already blind. He was actually a composer of modern music and he quite liked the idea to rent the apartment to a craftsman. He came by every now and then, and once he brought us to the door and said, "Ah yeah, you have certainly made to measure shoes," and he had as well, and I said, "You know what the difference is? It’s a sound when you click the heels, one to each other, this one," and that’s the difference of the [inaudible 00:34:53]. He said, "I do this one" and we both clicked our heels. That’s the sound of the heel of the made to measure shoe.

Sarah Monk (35:12):

Thanks to Gabrielle Gmeiner for sharing her story. You can discover more on her website, gabriellegmeiner.com or on Instagram @gabrielGmeiner. Thanks to you for listening. As with all episodes, you can find photographs of the work discussed on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, and on Instagram. If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, please subscribe to our newsletter on our website so we can let you know when the next episode goes live.