Xavier Montoy

Xavier Montoy grew up in a family of doctors and was always keen on biology, so when he took an artistic route he chose to focus attention on endangered insects to highlight how we should honour and conserve them.

As part of our Paris series, Mike Axinn and I go to the 11th arrondissement of the city to meet Xavier and see how he creates jewellery with the Sternocera beetle.

The Sternocera beetle

Necklace Plastron Gold

Necklace Plastron Blue

Colliers “Cartouche” bleus, 45 × 13mm

Sternocera aequisignata live in south-east Asia, especially in north-east Thailand. Their life cycle is two years, of which the period when they live above ground, reproduce and then die, lasts only a few weeks. Once a year, in September and October, villagers harvest and sort the elytra (fore-wings) which Xavier sources for his work.

Elytra, or fore-wings, of the Sternocera beetle

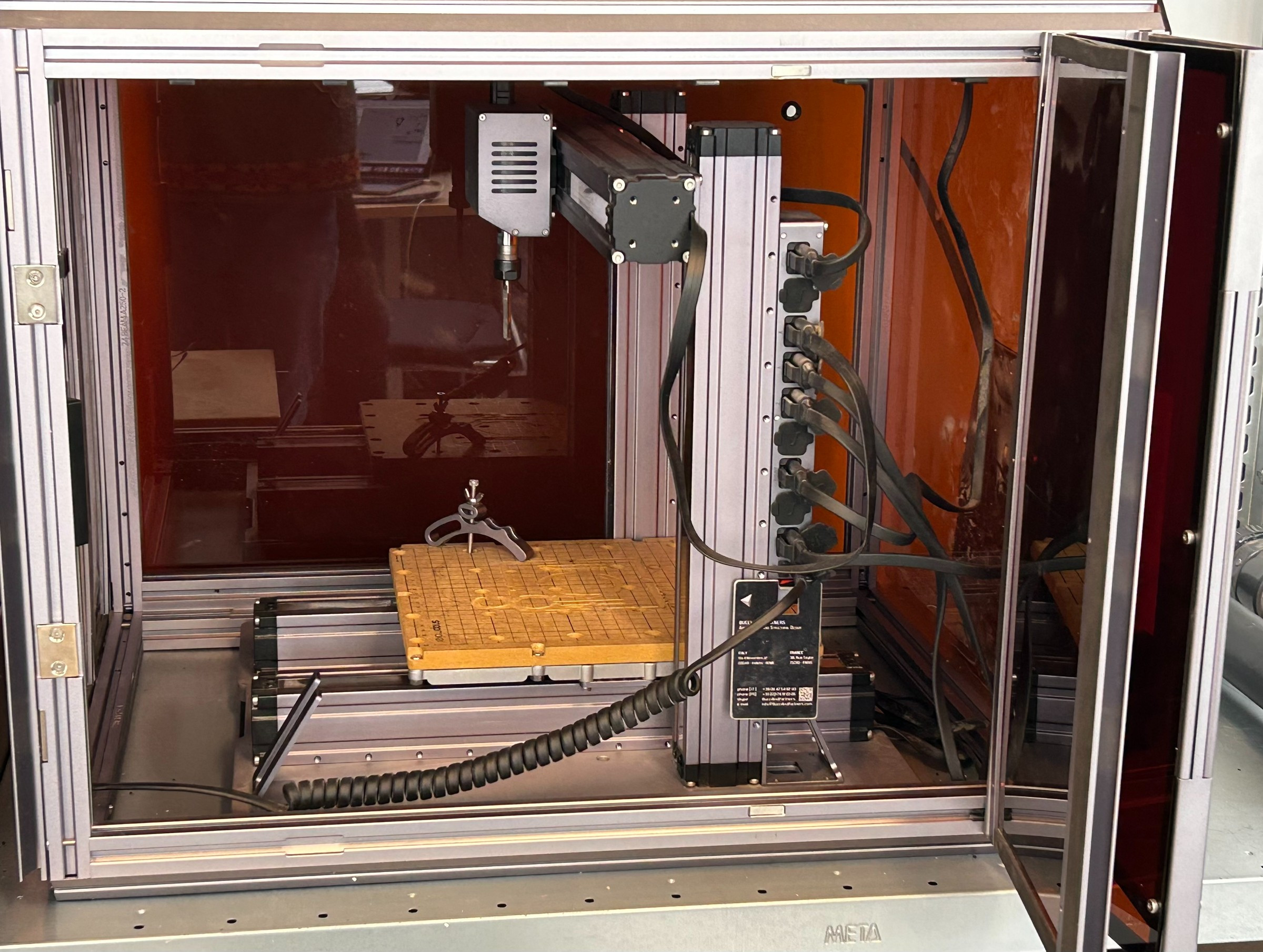

Xavier’s workshop is in the artisan complex at the Cité des Taillandiers, in rue des Taillandiers, where around twenty artists and artisans have workspaces thanks to an initiative of the mayor of the 11th who is working to support historic craft activities in the arrondissement.

In his shared, neat workspace we find a magical display-box of beetles and butterflies, some 3D-printing equipment and a case of jewellery tools.

On a high shelf are some precious sheets created from beetles in bright iridescent colours.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Epidemic Sound

Water Drops, by Clarence Reed

Xavier Montoy (00:00):

So I have big plank of beetle fragments and then I work with it. The craziest thing with those beetles is that they are iridescent. It’s a metallic color between blue and green, or it’s also gold or deep blue. Basically when I saw this material, I was like, okay, it is good to use biology to develop project and make science, but my feeling was it was most important to reveal the beauty of nature to make people understand that it’s such an amazing thing that when people will notice it, I hope they will be more conscious of the beauty of nature and the way that we have to take care of it.

Sarah Monk (01:06):

Hi, this is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Mike Axinn and I are in the 11th Arrondissement of Paris meeting Xavier Montoy whose passion for highlighting the importance of insects in the ecosystem has led him to create jewelry with the Sternocera beetle.

(01:26):

It’s a cool March morning and the colors seem very Parisian. A bluish gray veil is in the air as we walk past handsome Norman churches through wide boulevards towards Xavier’s workshop. Bicycles skim by, pedestrians pull their coat collars up as they march over the zebra crossings. The cafes are just waking up as we descend for our morning hit in one of the nouvelle vague coffee houses. Xavier meets us at the large industrial gates of the Cite de Taillandier, in rue Taillandier. Here around 20 artists and artisans have workspaces thanks to an initiative of the mayor of the 11th who is keen to support the preservation of historic craft activities in the arrondissement.

(02:09):

Upstairs, in his shared neat workspace, we see a magical display box of beetles and butterflies, a case of jewelry tools and some 3D printing equipment. Above on a shelf are some sheets of the precious metal he has created from beetles. We ask him to introduce himself.

Xavier Montoy (02:30):

My name is Xavier Montoy. So now we are at Cite des Taillandiers. It’s a place in Paris where designers and craftsmans can have a workshop to work in the middle of Paris. It’s developed by La Ville de Paris. You have designers, people who are working with paper, also with wood like Maxime Bellaunay. We have people working with algae also.

Sarah Monk (02:53):

With algae?

Xavier Montoy (02:54):

Yeah, algae. It’s a great place to also share knowledge and knowhow, and even we can share materials. If we need a machine or something that we don’t have, we can ask them if we can use their tools, so it’s a great place.

Sarah Monk (03:09):

I wonder whether we might go back to your story, really, where you were born and how you came to be doing this.

Xavier Montoy (03:17):

I was born in Rouen, a small city in the middle of France near Lyon. Well, for the anecdote, I was collecting insects with my grandfather when I was maybe five, six years old, and was really fascinated by insects. That’s how I, well, discover the beauty of nature. Way later in my work, I just re-find this insect collection and I was like, "Oh my God, yes. I forgot it. It’s beautiful." I was looking for different type of insect and I discovered the Sternocera aequisignata, which is the beetles I’m working with. They are responsibly collected. They are not in danger and we can easily find a big quantity of them. That’s why I work with these species exclusively.

Sarah Monk (04:06):

And when you were little, do you have a regular education or an art education?

Xavier Montoy (04:11):

I had a regular education and also more Cartesian education. I make a scientific baccalaureate study. I was really hesitating between medicine study or art studies. I had the intuition that it will be easier for me to bring biology and science into art and design than bring design and art into medicines. So that’s why I choose design.

Sarah Monk (04:38):

Are there artists in your family?

Xavier Montoy (04:39):

My grandfathers, as I said, my first grandfather loved nature and the other one that I never met dreamed of being a wood worker, but his family doesn’t allow it to do so, so he worked in [inaudible 00:04:53] or stuff like that. And my parents really pushed me to the arts education. And they are both medicine.

Sarah Monk (05:02):

They’re both doctors?

Xavier Montoy (05:02):

Doctors, yeah.

Sarah Monk (05:04):

Oh, wow.

Xavier Montoy (05:04):

And my brother also is doctor, so I’m the only one, the black sheep that was like, "I want to do arts."

Mike Axinn (05:09):

That’s very nice because they encouraged you.

Xavier Montoy (05:11):

Yeah, they were really supportive. So after the bacc I went to L’Ecole Boulle in Paris, a design school where I studied project design and then I went to L’ENSCI, Les Ateliers. It’s also a design school in Paris. It’s the only public school which is exclusively teaching industrial design. And this school was very nice for me because it’s a very free education and I had many project with biology and also researcher. And I work with L’Institut Pasteur in biology thanks to Gillian Grave which is designer specialized in biomimicry.

Sarah Monk (05:51):

What’s biomimicry?

Xavier Montoy (05:53):

Biomimicry aims to take inspiration from natural solution to apply them into engineering in order to be more ecological friendly or to find solution from the big problem we’re facing.

(06:08):

At the beginning I was more into science and design, so project about synthetic biology, which is developing some DNA pieces that you put into bacteria and then bacteria make you materials. That was a project with L’Institut Pasteur and it was for competition organized every year by the MIT in Boston. So we developed our project. We were 15 students, three designers, biologist, physics, and we went to the MIT and we won the gold medal for our project. That’s where I really start to focus more on biodesign.

Sarah Monk (06:48):

Gosh, congratulations. Can you tell us more about that? What DNA did you use?

Xavier Montoy (06:54):

In fact, we did not use DNA, it’s called bio bricks. It’s like Lego, the small blocks that you can put together. And it works almost the same with DNA. You can take some DNA pieces that have functions, we call it. So for example, to create silica to attach on specific material and then you can combine these DNA fragments to make your own production line of DNA. And then bacteria works almost like microscopic industry that produce the materials.

Mike Axinn (07:27):

And what were the materials that you were constructing?

Xavier Montoy (07:29):

We were focusing on the arboviruses, which are disease spread by mosquitoes. We develop materials that work like a test if you want to know if you are pregnant or not. So you just crush mosquitoes on it and it change color if the mosquitoes have arboviruses in it. Because the main problem with arboviruses is that there is no vaccines or treatment, so we have to know where are the infected mosquitoes to avoid a human to be contaminated. So these materials allow us to develop a whole project with a mosquito trap and another station with this material and that allow us to make a cartography of where the infected mosquitoes are and then to give this cartography to public government to then help people avoiding those area.

Mike Axinn (08:19):

And then what happened for you after that competition?

Xavier Montoy (08:22):

It was a student project, and then I have my diploma project, and I really started to question the way we use the livings for this project specifically because we were using bacteria and then modified our DNA to make them produce something. And then I focus on the relationship we have with the living species that share the world with us. And during those [inaudible 00:08:49] I make many researches and then I find the Sternocera aequisignata and here I start my project.

Mike Axinn (08:56):

Where did you find them?

Xavier Montoy (08:58):

They are originally from Thailand, and I discovered these species on internet. And then I contact a guy which has not a farm, but who has many of these beetles and they live in forest in Thailand. Those species live two years at larva, so underground. And they are three weeks during the year where they are adults. They go out of the ground, they reproduce and then they die. And once they died, they collect the beetles and they sell the shield.

(09:28):

Because it was an old tradition. And all my project was how to show this amazing material, which is iridescent and has amazing specificity in a different way because if you just show the insect, many people are, "Ah, yeah, but it’s a bug, it’s quite disgusting." Or, "Oh, poor bugs," or stuff like that. So I wanted to find a way to preserve the material and also to work with it easily because when you work with the shield directly, it has a specific shape and you can do whatever you want.

(09:59):

That’s how I come to crush them, make some fragment of them and I put them into cellulose acetate. So I have a composite material that I can work like wood, and then I work with this material to make jewelries and also some furniture.

Mike Axinn (10:17):

So right now you are buying them from Thailand? It’s sourcing?

Xavier Montoy (10:21):

Yeah. I just bought them once but it was 5,000 heliotrope. So I have big plank of beetle fragments and then I work with it. The craziest thing with those beetles is that they are iridescent. It’s a metallic color between blue and green, or it’s also gold or deep blue. The amazing fact is that it’s not color pigment, it’s what we call structural color. So it [inaudible 00:10:48] the relief on the top of the shield that defract the lights and give them those amazing colors. And so depending which what angle you look at the material, then the color change.

Mike Axinn (11:00):

You transitioned from working with MIT and winning prizes to this work. Was there a moment where you just went, "Wow, this is what I want to do."

Xavier Montoy (11:10):

Yeah. Basically when I saw this material, I was like, okay, it’s good to use biology to develop project and make science, but my feeling was it was most important to reveal the beauty of nature, to make people understand that it’s such an amazing thing that when people will notice it, I hope they will be more conscious of the beauty of nature and the way that we have to take care of it.

Mike Axinn (11:38):

What’s the reaction when you talk to people about, okay, you’re at a party or maybe with your parents and you say, "Okay, this is what I do." How do you explain it?

Xavier Montoy (11:47):

Well, at the beginning people look me like, "Okay, I think you’re crazy. You’re crushing insect and you say you want to protect nature." But once you take time to talk with them and you show the work, and I think also that the intention you put in your project is way more important than the object itself. So when you take time to talk with people to say, "Okay, just look at beautiful it is." And also that the species I’m working with is not in danger and is responsibly collected, then they start to understand. And also some people don’t understand and they’re like, "Okay, you’re just a strange guy." But also people say, "Okay, so I never look at insect this way." And then I say, "Okay, maybe it works a little bit."

Sarah Monk (12:31):

Another project I saw on your website I’d love to talk about or hear about, which is Imigos. Am I saying it right?

Xavier Montoy (12:38):

Imago, yeah.

Sarah Monk (12:39):

Can you tell us a little about that one?

Xavier Montoy (12:43):

Sure. So for Imago it was the same intention, which is showing the beauty of nature from another point of view. And so Imago or numeric collage.

Mike Axinn (12:51):

Collage?

Xavier Montoy (12:52):

Yeah. So I just find some picture of insects and then I assemble them together in another shape. And it also take inspiration from the psychology or…

Sarah Monk (13:06):

Psychology?

Xavier Montoy (13:06):

Yeah, psychology or the Rorschach test.

Mike Axinn (13:09):

Rorschach.

Xavier Montoy (13:10):

Rorschach, yeah, where you have some shapes and you have to say what you see in it. It’s the same here. It’s more abstract shapes that I create with pieces of insects and then people see whatever they want, but most importantly they don’t immediately see the insect. So they see the color, the different shape, and then they’re, "Oh, okay. It’s nice, I like it." And when they come closer, they see that it’s insects and then they’re, "Ah, okay."

(13:35):

I did the same with some fishes, which are called the Betas. I don’t know in English, but say "les combatants," the fighter fishes, because those fishes were used for fishes fight. Human take two of these fishes, put them in an aquarium and then make them fight. They also have crazy color, crazy shapes, but just when you put two male together, they start to fight. And so like the chicken fights in yard, there also is fish fights.

(14:06):

But this project is more, it’s clear an artistic one. And also, I make many drawings. This was another expression territory for me to work with pictures.

(14:18):

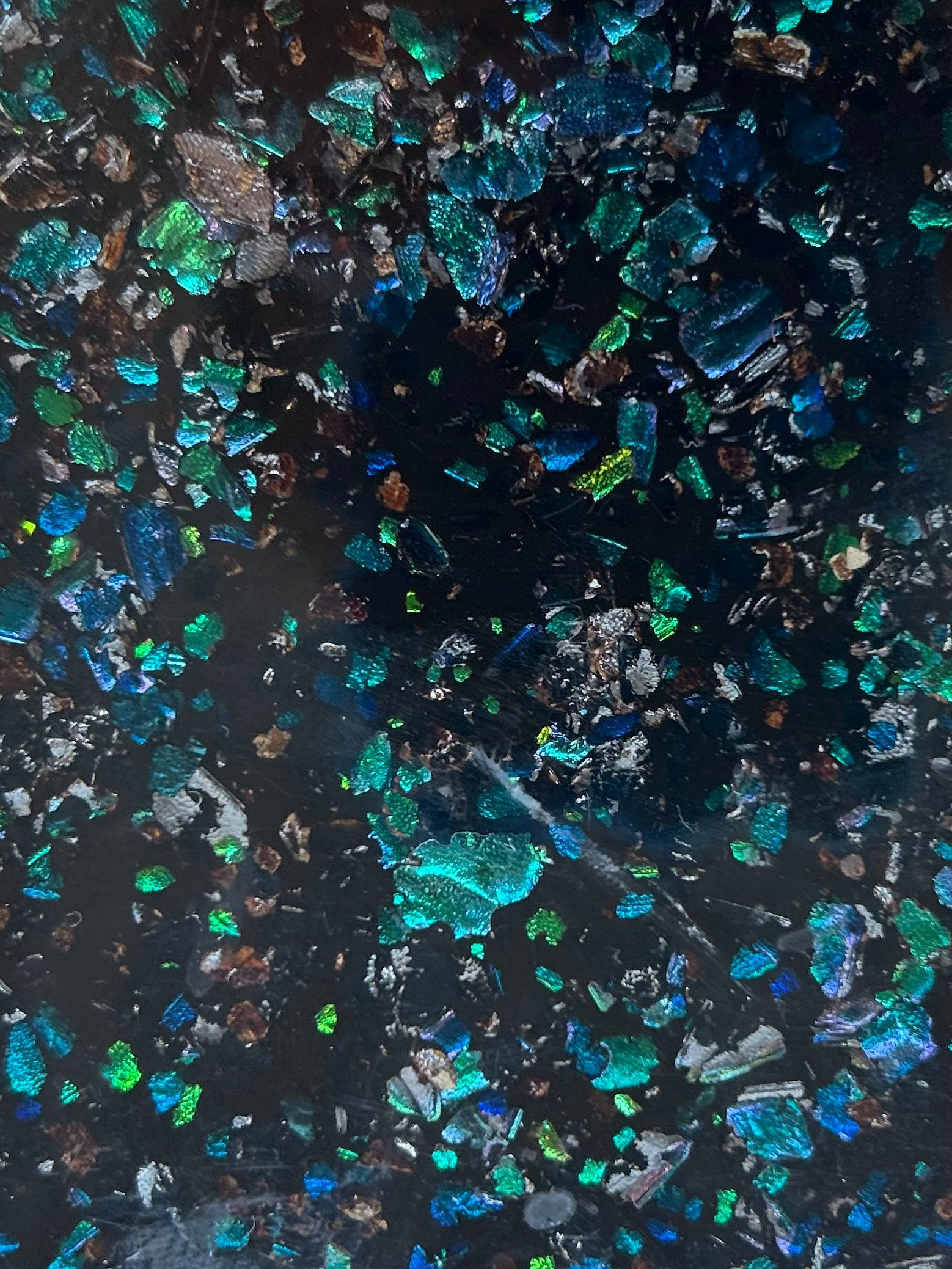

So I develop material with the beetle shields and I’m working with a society which is an expert of acetate cellulose transformation. So I have a dark sheet of acetate de cellulose and a transparent one. I put my beetle shield fragment on top of the black one, and then the transparent one is pressed on top of the other and it encapsulates the fragment of the shields in it. Then I have this material that I am working with.

Sarah Monk (14:47):

Oh, wow. It’s beautiful. So it sparkles, it’s iridescent, the base is black, and then we’ve got these beautiful blues and turquoises and greens.

Xavier Montoy (14:57):

They are also called beetle jewels in Thailand, a very short part of time where they’re like this. They go out of the crown, reproduce and then die.

Sarah Monk (15:06):

We were talking about the biodiversity and what would be the loss to the world if they did not exist?

Xavier Montoy (15:12):

The thing is that we can’t know. It was the same for the mosquito, is our project. And people say, "Okay, but why don’t we erase mosquito from the Earth?" But every time a species disappear, we have many changes in the biodiversity and it can be terrible. But for example, if you have no more insect, then you have no more birds. If you have no more birds, then you have no more foxes or mammals that eat birds and then it starts to fall apart.

(15:40):

That’s also the beauty of it is that it’s here. For example, why are those beetles iridescent? We have no idea, but they are. That’s quite amazing because there is no really interest of developing such a material. There’s many billions of years to develop this specific structure on the shell to then defract the light and maybe just to attract the sexual partner or something like that, but we don’t really know why, but that’s how it works.

Sarah Monk (16:09):

There’s a certain irony in such a beautiful and colorful species being underground.

Xavier Montoy (16:14):

Yeah, yeah.

Sarah Monk (16:15):

For two years and only above ground for two weeks.

Xavier Montoy (16:19):

Yeah, sure, but it’s the same for the butterflies. I have many butterflies with crazy and amazing colors and they are like chrysalid and larva for months and the butterfly live only few days. That’s a metaphor of the living that is beautiful but very fragile. And so we have to enjoy it as long as you can and make sure we don’t destroy it, or at least that we noticed it, for me it’s the most important.

Mike Axinn (16:43):

Coming back to what you said earlier about your studies with the guy who learns about functionality from nature.

Xavier Montoy (16:51):

Yeah, biomimicry.

Mike Axinn (16:52):

Has that come into your thinking when you do this work?

Xavier Montoy (16:56):

Yeah, sure. I wouldn’t be there where I am today if I didn’t meet Gillian Grave and if I didn’t start to learn about biomimicry, because that’s where I discover how amazing nature was. For example, you have the spider, their web is way more resistant than the titanium or any metal we can make at the same proportion. You have also the termites, which are small insects, and they invented air conditioning without having to invent electricity because they live in what we call termite mount, and they have to keep live a small mushroom in the center of the termite mount. To do so, the air has to be about 20 degrees, I think. And they’re living in Africa where the outside temperature can be 40 degrees, and during the night minus one or zero degrees. To do so they have many pipes into the termite months that make the air be cooling down during the days and warmer during the night.

(17:54):

So nature has developed millions of technique to solve the same problem or same issue that we are facing and we just have to look at it to find more sustainable solution to some of our problematics.

Mike Axinn (18:07):

What about color? How does your own ability with color figure here?

Xavier Montoy (18:12):

The funny thing is that I’m kind of colorblind.

Mike Axinn (18:16):

Me too.

Xavier Montoy (18:17):

Perfect. During my studies I was very uncomfortable with color because I couldn’t work with it. I was not very sensible to it. And I think also that the fact that I’m working with already existing colors that I don’t have to choose helps me a lot also because, well, I can’t decide the color of the shell, so I have to work with it. Hopefully it’s beautiful color.

Mike Axinn (18:41):

And my theory is that because we’re colorblind, we compensate with a perception of light.

Xavier Montoy (18:48):

Well, I’m not expert on it, but if you say so, yeah. But also with shapes. For me, the shapes are very important. I don’t know if it’s more than people that are not colorblind, but really the Imago project, it’s more about shapes than about color. We have the original beetle, then there is what we call heliotrope, so that’s the part of the shield that protect the wings and also the sound that they make, it’s quite interesting, like metal parts. And so I have those. Then I crush them into small fragments that you have here. And then those fragments, I use them to make my composite material that you see here.

(19:31):

There are three different color of these beetles. It’s like our eyes. It’s genetic mutation. They are green, gold and blue. And the green one are the most common one. It’s 99% of the species that are green. And the blue and gold one is like 1%, so it’s more rare. This one.

Mike Axinn (19:52):

Oh, madness.

Xavier Montoy (19:52):

And so I told you like this, it’s very green. And when you look at it like that is becoming blue.

Sarah Monk (19:58):

Tell us the process.

Xavier Montoy (19:59):

For the furniture and specifically for the jewels, I work on computer. It’s almost the same process I use for the Imago, which is I have some shapes I like and I collect them and then I start to assemble them. And if you look the jewels, you have two shapes. So it’s this one which is like an oval and small circle. And for this one I was inspired by the Egyptian shapes.

Sarah Monk (20:26):

I was going to say it looks Egyptian. So they’re the circles, but they’ve got a lovely beautiful frame around them of a metal design.

Xavier Montoy (20:34):

Yeah. Beetles in Egyptian mythology is very present. And also, this year, the anniversary of the discovery of the Tutankhamen Tomb, I think. That’s why I developed those shapes last year for this.

(20:48):

But as I said, we know that there are plenty of diamond into our universe. We have full planets made out of diamond, for example. We have meteorites that people want to go and to take the mineral diamond and bring them back to Earth. But those species, like those beetles, as long as we know we only have them on Earth, and once the species has disappear, there will never be anymore this material anywhere in the universe. That’s also what I want to show is that the preciousness of this material, and that’s why I wanted to make jewel out of them.

(21:23):

In this box you have many of my insect collection and some of them were collected by my grandfather. Almost all of them are in danger, so I don’t want to work with them because we just have to let them live. If you zoom in it, so you have to make it closer, you can see that it’s small pieces, small [French 00:21:43].

Mike Axinn (21:41):

Scales.

Xavier Montoy (21:43):

Scales like turtles. So here we have a 3D printer. This one and this one are 3D printers, so it allows me to make prototype of the jewel or small pieces I’m designing because I’m working on my computer. So first of all, I make some drawings, then I go on the 3D and my computer, then I print some prototype here in resin.

Sarah Monk (22:07):

Yes, resin. The material that you’ve created, you’ve got these beautiful squares now of the beetle material, so you put that into this machine?

Xavier Montoy (22:16):

Yeah, I put that into this machine. And then with the client, we can select the piece of material and then I can cut it. Once I’m happy with the shape, I print them with wax and then send them to the metallurgist. And then I have my pieces in silver or gold. Sometimes the jewels can look similar or have some inspiration in it because I really like symmetry.

Mike Axinn (22:39):

What is your hope as far as what you accomplish with this?

Xavier Montoy (22:42):

My hope is that people will start looking differently at the living that share the world with us. If they don’t like my work, as long as they are starting questioning their perception of the living, then for me it’s good because normally they understand it. They can disagree with me but we are starting a discussion and that’s the most important part because I think also that art is a way to start a discussion about any topics in the world.

Sarah Monk (23:14):

So thanks to Xavier Montoy. You can discover more about him on his website, xaviermontoy.com, or find him on Instagram at xavier_montoy. And thanks to you for listening. As with all episodes, you can find photographs of the work discussed on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, or on Instagram @materiallyspeakingpodcast. If you’re enjoying Materially speaking, please subscribe to our newsletter on our website so we can let you know when the next episode goes live.