Usama Alnassar, 2024. Photo: Gail Skoff

A sculptor and painter born in Damascus, Usama tells of the impact of being brought up in Syria and of continuously dealing with people from different religions with diverse ways of looking at things.

Photo: Gail Skoff

Usama’s studio space, and home, is tucked away in the shadow of the statuario marble quarries. Usama bought the space in this historic marble area because he felt an urgency to build a stone amphitheatre there. Initially he dismissed the land because he feared flooding. But he worked non-stop his first winter to build his theatre.

Usama Alnassar, Amphitheatre. Photo: Usama Alnassar

Usama Alnassar, The Music Stairs. Photo: Gail Skoff

He tells us about his childhood and how it informed the person he’s become. His uncles are both sculptors and their books on marble, in his grandmother’s library, inspired him from a young age. First he studied art in Damascus, where he carved in wood, and then he came to Carrara to study sculpting in marble.

Usama Alnassar. Photo: Gail Skoff

Usama talks about his relationship with nature and his love of plants. He grew up in Syria with a family garden of fruit and vegetables, and always loved working in nature. He has planted many trees and plants in his Carrara home.

Usama Alnassar. Photo: Gail Skoff

Many of Usama’s pieces are inspired by immigration There’s a wall of marble blocks sculpted with luggage handles, straps and zips. He tells how immigrants who used to carry lots of luggage now find their luggage has become much smaller, sometimes even just a mobile phone.

Usama Alnassar, Icon Woman

Usama created a series of sculptures of women depicting the life of women in the Middle East and their freedom to travel around. His sculptures explore how women have sometimes been transformed by religion into more of an icon than a person, and how this can also become a prison. However, they often find virtual freedom through the internet.

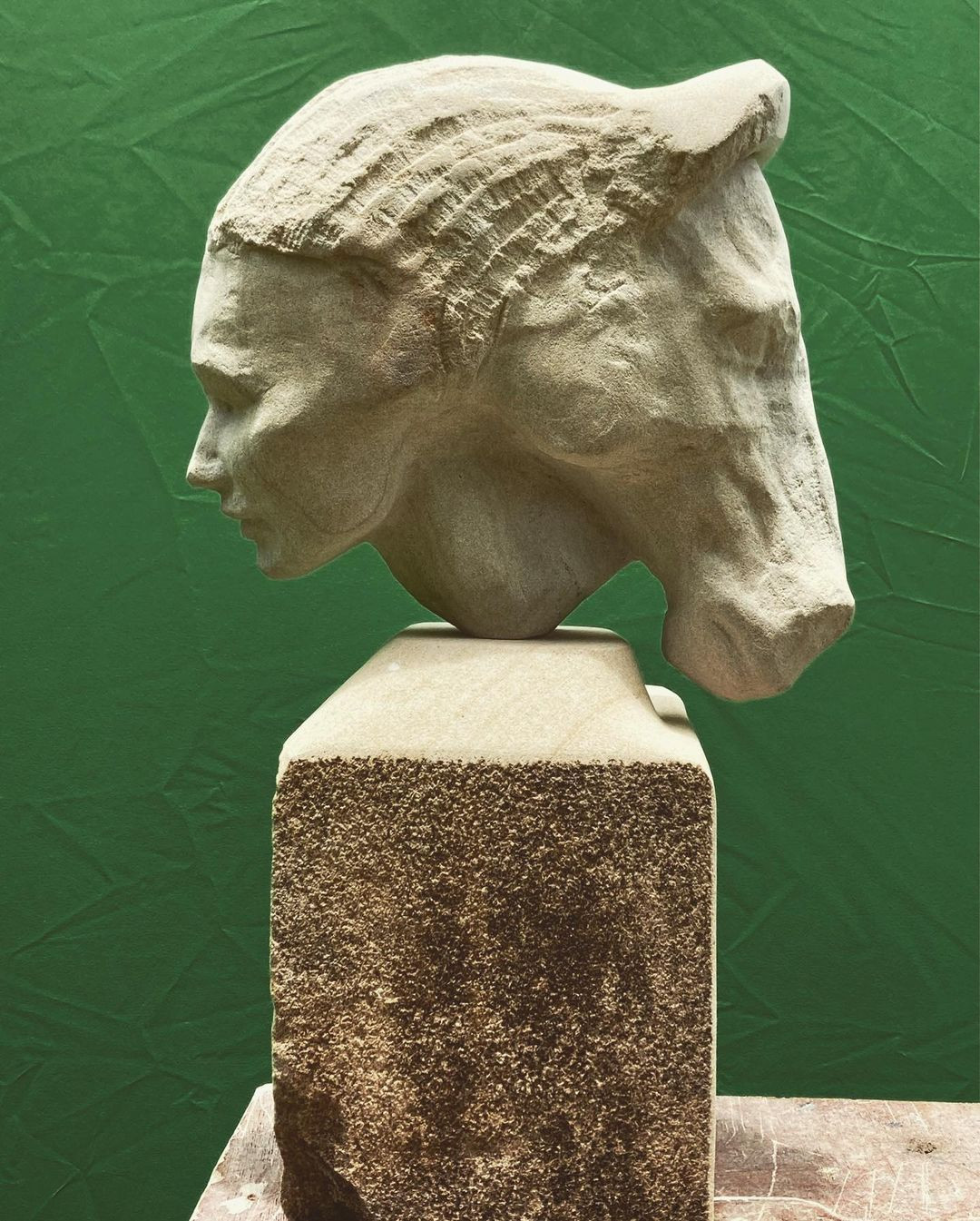

Usama Alnassar, Horse Woman

This piece is a woman on one side and on the other side a horse, her hair represents an extension of her thoughts.

Usama loves teaching and sharing his skills whilst allowing his students to develop their own personalities in their work.

Sarah and Usama, 2024. Photo: Gail Skoff

Credits

Thanks to Gail Skoff for collaborating on Usama's episode and for the fantastic photographs.

Gail Skoff, gailskoff.com – instagram.com/skoffupclose

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Call to Beroea 1401/3, Luke Richards

So I drove up and the sky was blue like never seen that before. And I looked at the place, and it was totally destroyed. But there was a curved wall built with huge blocks and rocks of marble. And I thought this looks like a piece of theater. I could build a theater here.

Usama Alnassar:I didn’t look at the house. I didn’t look at the studio, the space, what I could do, what I couldn’t do. The only interesting thing in my mind which drove me totally blind was the idea of building a theater. I’ve spent like 7 months during the winter, nonstop working on that. And in the spring, I had this theater.

Usama Alnassar:I said, why did I build a theater? I’m not an actor. I’m not a singer. I don’t organize events. I’m not a party guy.

Usama Alnassar:That was a mystery in my life. It took me a couple of years to find the answer, and the answer was much more profound than I could imagine.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of materially speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Gail Scoff, the photographer, and I are winding up dusty white roads to the marble quarries of Carrara. Giant lorries laden with marble thunder past us as we give them a wide berth, and soon the ice white quarries tower over us. We’ve come up here so I can interview and Gail can photograph Usama Alnassar, a Syrian sculptor.

Sarah Monk:A sharp turn off the road and we find Usama walking out to greet us. Okay, so we did get a little lost. His studio space and home is tucked away, hidden against the mountainside. There’s a yellow truck for moving stone, interlinking marble tables for communal eating and a huge brown dog. We see a wall of marble blocks sculpted with luggage handles, straps and zips.

Sarah Monk:There are sculptures of women and of horses too. But our eyes are drawn to a huge round space with chunks of marble arranged in tiered seating and large slabs forming a back. What on earth is an amphitheatre doing up here? I ask Usama to introduce himself.

Usama Alnassar:My name is Usama Alnassar. I’m a sculptor and painter. I was born in Syria, in Damascus, one of the oldest cities on earth, which has definitely left in me lots of deep memories. I’ve studied art in Damascus. I’ve studied painting there.

Usama Alnassar:But then I moved to Italy. I moved to Carrara to study sculpture in one of the most famous sculpture academies in the world.

Sarah Monk:So are your family artistic?

Usama Alnassar:Well, I have 2 of my uncles. They are sculptors, and they are actually very good sculptors. One of them still lives in Carrara, and the other one lives in France. But both of them have studied here in Carrara in the academy. So probably that was the reason why I also came here to this spot.

Sarah Monk:So tell me about your childhood. What was it like in Syria growing up?

Usama Alnassar:Well, I have to say that, my childhood was a big portion of why I am like this today. Basically, to grow up in Syria means that you have to learn how to deal with the other people from different religions and to learn all these different tonalities that are not easy to understand. Obviously, when you are talking to someone from a different religion, it feels like you are talking to an alien or someone from a total different culture, and you have to deal with that. That is a rich thing, but at the same time, it can lead you into deep troubles.

Sarah Monk:And why did you leave Syria?

Usama Alnassar:I started looking for some different possibilities, and I thought I’ll apply for the academy in Carrara. And if they say yes, then I’ll go to Italy. When I was a teenage, my both uncles have left a beautiful collection of books about the Renaissance sculptures in Italy, especially about Michelangelo sculptures and etcetera. So when I used to visit my grandmother, the library there was like an erotic thing for me. I would spend hours looking at these sculptures.

Usama Alnassar:Although I have never thought about studying sculptures or becoming a sculptor, I thought I would become an architect, actually. But things happens.

Sarah Monk:So after you finished your studies in Syria

Usama Alnassar:I thought I would come to a place that looked like Paris in the twenties or something, but it was not like that. I was very superficial, I would say, and things were not that profound. Although I was still very enthusiastic, so I tried my best to not let it go. And I start having exhibitions, doing things, and creating and studying at the same time.

Sarah Monk:So what materials were you working in at this point, Usama?

Usama Alnassar:Well, when I came here, I have already worked with wood, and I’ve created lots of sculptures and, different things. But as soon as I arrived here, actually, I couldn’t wait to touch marble, so I started at once. And I have to say that marble seemed to be very easy to work with, especially with the right tools. So I thought, that’s a good thing. Maybe I should teach people to sculpt it.

Usama Alnassar:You know? Because sometimes people can do things because of the lack of knowledge, not because it’s difficult to do it. So I started teaching soon after that.

Sarah Monk:So you like teaching?

Usama Alnassar:Yeah. I enjoy the fact that, actually, I could give someone the knowledge. It’s not a job for me. It’s the fun of trying to teach people how to learn something without invading their process. That kick that comes along when someone is trying.

Usama Alnassar:So giving little things at the time to learn, but keeping a space for someone to have his own personality in his work and her work. That’s what I enjoy. Nice.

Sarah Monk:So can you tell us where we are now and what we see when we look around us?

Usama Alnassar:Yeah. We are here in, between the mountains in Carrara, and this is, in particular, this valley, one of 4 valleys in the mountains where they have actually marble, and they extract marble. So there are maybe 70 to 80 quarries that are still active in Carrara. But in this particular valley, you would find the statuary marble, and that’s what most sculptors would love to use for their creatures. So it has a special history, and, not only history of beauty and wealth, but also a history of lots of conflicts, lots of sufferance, and lots of contrast between nature and what humans would do to this nature.

Usama Alnassar:So you would look on one side of the valley and you will see marble being cut like cheese, but on the other side, you would see nature.

Sarah Monk:Where we’re sitting, you’ve sort of carved your workshop into the mountain, so you have marble pieces. And you have a big passion flower growing, which is just coming into flower. Tell me about your relationship with nature in your garden.

Usama Alnassar:Well, I grew up with my dad and my brother. We had, this garden with fruit and vegetable. And probably that was also an important part of my memory. But I always loved walking in the nature, at least when I was in Syria. So I had a specific and good connection to the nature.

Usama Alnassar:So when I started restoring this place and rebuilding my studio, I’ve started digging holes here and there, filling up that with soil, and planting trees. So now the place is full of trees, plants. Some I’ve planted. Some grew up on their own, and that is a rich thing for me. And it reflects actually very much what happens around the studio.

Usama Alnassar:So lots of nature, lots of wildlife, and lots of man made cutting blocks, moving loads of tracks full of marble.

Sarah Monk:It does feel like a very industrial place until you find this little oasis. How did you find it? When did you move here to this place?

Usama Alnassar:Well, it’s a funny story. The place was for sale for almost 4 years, and an interesting guy, an artist actually, who was in charge to sell the place. He did his best to not sell it to whoever. Especially, he made his best to not sell this place to another owner of quarries because he didn’t want this place to become a deposit for marble blocks or anything like that.

Sarah Monk:Was it a studio before?

Usama Alnassar:Exactly. Before that, this place was owned by a Hungarian sculptor. His name was Janos Stryk, and he rented lots of spots in the studio to many different sculptors. And often, they had a place to sleep like a caravan or little cottage. So anyhow, when I saw the place, it was raining heavily.

Usama Alnassar:And a few months before, there was the biggest flood in the history of Carrara, and I thought, no. I’m not gonna buy anything in this area amongst the mountain where the risk of flood is very high. So I went back to Carrara without even looking at the place. Anyhow, the same day it was in March, the sun came out, The cloud disappeared. And I thought to myself, you know what?

Usama Alnassar:I’ll take a look just so I know why I say no. I’m not gonna buy this place. So I drove up, and the sky was blue like never seen that before. I looked up, and finally, I could see the mountains, and they were incredibly beautiful and amazing, I have to say. And I looked at the place, and it was totally destroyed, but it was in the most beautiful and interesting part of the world.

Usama Alnassar:And there was a curved wall, a big curved wall, built with huge blocks and rocks of marble, and I thought this looks like a piece of theater. I could build a theater here, and I couldn’t think about anything else. I didn’t look at the house. I didn’t look at the studio, the space, what I could do, what I couldn’t do. The only thing I could see was this wall, and the only interesting thing in my mind, which drove me totally blind, and I could see only that was the idea of building a theater, and I was so enthusiastic about the place that I asked my uncle, please give me the number of the owner.

Usama Alnassar:And he looked at me, and he understood how much I love this place. So we called the owner, and I told her, if you come tomorrow, I’ll buy the place. She couldn’t believe she was happy. She came the day after we went to the notary guy, and we signed the contract. And we came up, both of us, actually, to this spot.

Usama Alnassar:She opened the door of the house. And so for first time, I could see the house after I bought it.

Sarah Monk:Oh, that’s funny. So you didn’t even go inside.

Usama Alnassar:I didn’t go inside at all.

Sarah Monk:So tell me about theater then. Is theater a large part of your life?

Usama Alnassar:Yeah. Actually, that’s an interesting question. Actually, I’ve spent, like, 7 months during the winter nonstop working on that. And in the spring, I had this theater, marble theater, amphitheater, and it looked stunning. It looked beautiful with 1 meter 60 tall sculptures standing on the wall, a little bit like in the Greek theaters.

Sarah Monk:So why did you want to have a theater?

Usama Alnassar:I asked myself the same question. I said, why did I build a theater? And I thought, I’m not an actor. I’m not a singer. I don’t organize events.

Usama Alnassar:I’m not a party guy. So why did I build a theater? That was a mystery in my life. So I’ve started thinking about that. It took me a couple of years to find the answer, and the answer was much more profound than I could imagine.

Usama Alnassar:When I was young, a teenage also, we would go, me and my family, to visit this amphitheater in the south of Syria. It’s called Basra Theater. Pavarotti once sang in this place also. The interesting thing is that whenever I was inside this big theater, I would feel like the time have stopped, and I would not think about any bad conflicts, but only beauty, art. I would imagine dancers and singers and actors, and I would see just the beauty of sculptures and architecture of the place.

Usama Alnassar:So I would see just a human expression, and I wouldn’t see any conflicts. And that has a lot of meaning for me because Syria is a country where there are lots of conflicts. I grew up looking at conflicts, living conflicts. Wars here, wars there, and that ended with the last 12 years of drama, war, and disasters, and something unbelievable. So I understood that building the theater, having a theater is for me as to build a place where I could sit inside and feel myself isolated from wars and conflicts and troubles and wars.

Usama Alnassar:There was a place to be connected more to myself and humanity away from conflicts.

Sarah Monk:That’s very beautiful. Because I think I thought you were gonna say because it gives people voice or gave you a voice, but actually it’s almost the opposite. It’s a place of peace, not of creating and sharing a voice. It’s more of a refuge.

Usama Alnassar:Yes. So probably more to be a spectator Yeah. And feel myself part of actually, the theater is a place where people sit and contemplate more than judge and criticize. And this is a wonderful value that human has sometimes.

Sarah Monk:So I’m realizing as I look at it that your work these works we’re talking about anyway are not for sale. They’re not pieces that you’re making to go in a gallery. They’re very site specific. They’re your home.

Usama Alnassar:Most of what you see here is made to be here, not made to be sold or moved away. I thought about how great it is when a sculptor or one artist have the possibility to create a world of his poetry, thoughts, and philosophy. In Oslo, a 100 years ago, the city, the Shire, the city, the commune, what they call the commune, gave the possibility to this sculptor whose name is Vigeland to build a park with his sculptures. But what if that artist has no possibilities, like no one to support you economically? This wonderful philosophy may disappear forever.

Usama Alnassar:And I thought, well, I have the duty to protect my philosophy in life. I will do my best to turn it into one place with all of these thoughts. As a human being, I have to protect my thoughts as an artist, and that’s the beginning of it.

Sarah Monk:Can you tell me a little bit about some of the work? Because I’m seeing some around the theater. I’m particularly seeing a lot of luggage handles.

Usama Alnassar:So this is what I call the digital horse, the fastest horse. So me as a immigrant who had to move between countries carrying a luggage. Now my luggage became very tiny. It became a mobile phone. While before, I had to bring lots of memories in my imagination, lots of colors and thoughts and sounds from my childhood.

Usama Alnassar:Now everything is recorded, and you can actually see lots of things through social media. But in that period of time, the world was facing the biggest changes in human history, moving towards digital era with no limit of speed and possibilities. But most of all, there was an element of migration that was running through the digital media. So people would travel around the world and explore possibilities and places without even moving away from the sofa. Just using a mobile phone, social media, Google, YouTube.

Usama Alnassar:So I wanted to actually record that thing, the change in the world. So I built this wall, which is almost 36 meters long and 3 or 4 high with blocks of marble, then I’ve sculpted them to talk about the migration. The migration was not anymore the migration of 1 person carrying a luggage and moving with it, but it became the migration of someone who puts himself in a luggage and becomes the luggage that can move anytime and anywhere. But apart from this history of immigration, which is more like my personal history, I’ve been, for example, looking at, the life of women in the Middle East, especially women who have particular difficulty in being connected to the world and having more freedom in traveling around. So I made actually lots of sculptures describing the life of a woman under these restrictions.

Usama Alnassar:For example, lots of my sculptures are about how women have been seen in the religion, transformed into an icon. They lost actually their nature by being woman, and they became a symbol of purity for some, and they had to be protected. So often this protection became their prison, their straight jacket, and the icon in which they are painted or sculpted, socially talking, that protection became actually the trap itself where they can go out. And some of these women actually found another way of escaping through the digital world where they could without going out of their house, they could travel the world just by using Internet. It’s very difficult to Western people to understand that.

Sarah Monk:So is there a specific example you can share?

Usama Alnassar:Yeah. We are sitting next to this woman. It’s called the icon woman. And it feel totally like a holy figure, like a Madonna, for example.

Sarah Monk:Yes. She’s got sort of a halo above her over her head, so she’s revered in some way.

Usama Alnassar:And it could look similar to the orthodox icon or the image of even some religious, woman veiled. But this veil is actually a trap, so it’s nailed around the figure itself. And everything is covered with lots of letters, Latin and Arabic mixed together. That they make no sense, but just like the jungle of information in which we live today, especially through the social media and the the opening to the world. So you see women still have an old education in a closed mind societies, but they live also the new era coming through lots of information.

Sarah Monk:So they’re still treated the same way in society, but, actually, they have access to a lot more information.

Usama Alnassar:And freedom at the same time. So after that, I made actually a few sculptures. I call them the horse woman, referring to the digital horse and this power that some of these women could gain. So from one side, you will see a woman face, and from the other side, there’s a metamorphosis into a horse head, but it looks like her hair. So it’s almost like an extension of her thoughts.

Usama Alnassar:Really interesting.

Sarah Monk:Can we go back to talk a little bit about migration? Because it’s obviously a very strong part of your identity.

Usama Alnassar:I’ve made few sculptures, actually. One of them is a man standing up, and this man is a migrant. This man have lost his face and his features. That’s what happened to the migrant. When someone moves from one to another reality, first thing is this person would face new values and new standard.

Usama Alnassar:It’s like when you look at yourself in the mirror every day, and you recognize your features, you recognize your face, and say, this is me. I know this is me. This is me means that I recognize the social life, the culture, the language, the songs. When I say something to my sister, to my father, to my partner, they understand. They feel what I’m feeling.

Usama Alnassar:But when you move to another place, you look into the mirror, actually, and you don’t recognize your features, Culturally talking. So this is one of the biggest problem in migration, and this is the biggest problem that migrants face.

Sarah Monk:So does this feel like home now for you, or what’s your relationship to home?

Usama Alnassar:It feels home. I feel home in inside myself, actually. So wherever I travel, I feel home. I have to say that I am lucky in that sense. I don’t feel that I’m missing things.

Sarah Monk:With your students, do you have a piece of advice that you like to share with them or would share with them?

Usama Alnassar:Making a sculpture in marble is like living a real life. It takes what it takes, and whatever you make, it’s one way. You can’t replace it. But you can look at it always and accept it and do new things to it. It’s useless to regret things, but whatever happens, it takes you to another situation.

Usama Alnassar:And you could decide if you are part of it or you like to be away from it. But to be open minded and accept what happens in your sculpture makes you accept many things in life and be more open to the change itself.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to Usama. You can see his work on his website, alnasaar.it , or on Instagram at alnasaarsculpture. As always, you can find photographs of the work discussed today on our website, materially speaking.com, and on Instagram at materially speaking podcast. If you enjoy Materially Speaking, please join our community and sign up to our newsletter on our website. We’ll then update you on future episodes and special events.