Sylvain has always loved cooking, but when he discovered a passion for working with metal and wood, he retrained in order to create kitchen knives for chefs.

Mike Axinn and I travelled to Paris to meet four artisans. In the first of our series on who we met there, we talk with Sylvain Maenhout who took the decision to retrain as an artisan in his late 30s. Becoming an artisan has given him the ability to work from home and have a more balanced, family-centred life.

Sylvain Maenhout

As is the case in most cities, finding a workspace in central Paris has become increasingly expensive. There are also tight restrictions on noise and dust. So Sylvain Maenhout made the move to an eastern suburb, ten kilometres out of town in Nogent-sur-Marne.

We chatted with Sylvain about his background and how he worked in business before choosing a very different path: becoming a blacksmith making kitchen knives.

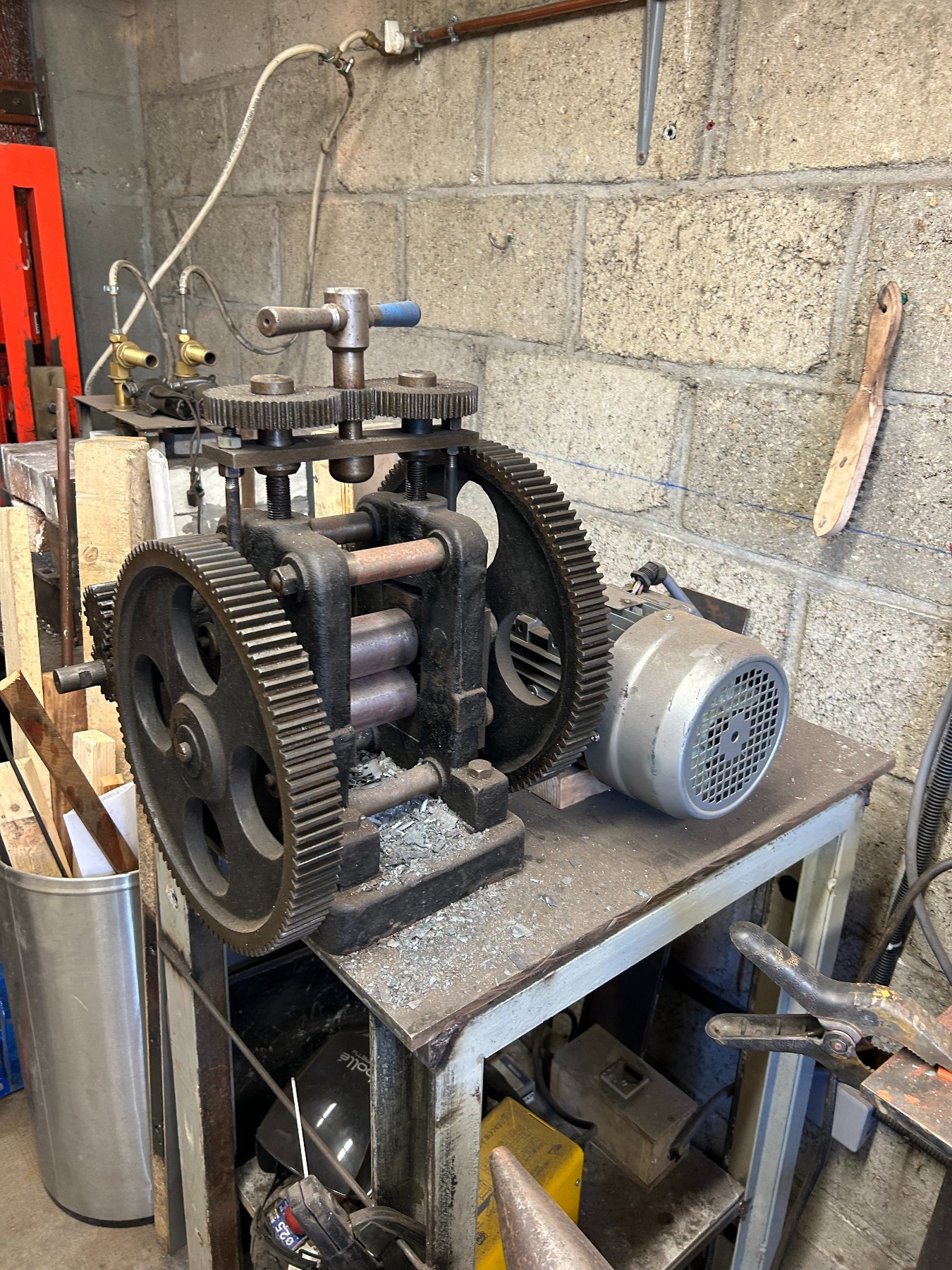

We visited Sylvain’s workshops – the first dedicated to metalwork – which had a 1950s rolling mill, anvil and hammer, and hydraulic press.

He tells of his passion for forging and how he loves working both with metal and wood. He explains how he sources his materials – steel from Germany and wood from suppliers who have already seasoned it.

Sylvain’s supplies of metal for knives

Then we go down to the basement where he has a second workspace dedicated to woodwork and knife assembly. In the house’s former coal-room he shows us where he does the heat treatments and sharpens the knives he’s making with Japanese wet stones.

Sylvain’s Japanese wet stones for polishing

Sylvain tells us about the range of knives he creates and his experiences talking with professional chefs and private customers.

Sylvain’s work-in-progress knives

Links

instagram.com/sylvain.m.coutelier

We mention the farm-to-table restaurant Les Résistants. And for French speakers, this interview with Sylvain (dialogue in French, though YouTube auto-translated captions available).

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Loin De Toi 3051/2, Cyril Giroux, Campbell E Browning, Vincent Tirilly, David Bossan

Sylvain Maenhout (00:15):

There’s something really hypnotic about the forging process, the hot steel, this really cold, hard material that you can shape as you want. It’s just a bit of magic really. When you actually have finished the work, sharpen the knife and you just slice through some kind of tomato, whatever else, and the feeling that you get at this point is just wow.

Sarah Monk (00:42):

Hi, this is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Mike Axinn and I are in Paris meeting artisans. Finding workspace here has become increasingly difficult. Rents are high and there are restrictions on noise and dust, so we weren’t surprised to find that Sylvain Maenhout, the first artisan we’re meeting, has recently moved to an Eastern suburb, 10 kilometers out of town. We catch the [inaudible 00:01:10] from Gare de Lyon and in 20 minutes are in [foreign language 00:01:14]. A short walk from the quiet station, we find Sylvain’s street where pretty 1920s houses have family cars parked outside. In the garden, we meet his partner, Aurelie, a journalist crouching in a fire bed, pruning roses. Our interview will include a visit to Sylvain’s workshops, one dedicated to metalwork with milling machine anvil and hammer and forging equipment, and a second space for woodwork and knife assembly. We asked him to introduce himself.

Sylvain Maenhout (01:45):

I’m Sylvain Maenhout. I’m 42, actually, I’m French based around Paris. I, [foreign language 00:01:55]. And I’ve been a knife maker, a professional knife maker for the past five years now. I had a first career in IT services and I decided to move to craftsmanship a few years ago. I’m the father of two. My partner, Aurelie, is a journalist, and I’m now working from our house, which makes things very easy and allows us to kind of manage work-life balance as well, which was one of the main purpose of may change of career. And obviously working from home, which has been the case for the past six months now or nine months since we moved into the house, it gives a lot of flexibility. So the kids’ school is at the end of the street basically like five minutes away, and if ever there’s any urgency, I can just stop my work and go there.

Sarah Monk (02:41):

Did you have the seeds of craftsmanship in your childhood or in your family?

Sylvain Maenhout (02:46):

Actually, not at all. No. That was a weird thing, but well, I come from the countryside in the north of France. My parents are from a generation where you used to do a lot of things yourself just because you just didn’t necessarily have a lot of money. So they built a lot of stuff themselves in the house. So I’ve always seen my father do things with his hands, but not as a job, right. Just because it needed to be done. What happened is obviously I’m from a generation where we’ve been pushed a bit to intellectual kind of careers if possible, which I did. And actually when I announced to my father that I wanted to change career and go to craftsmanship, it went like, not you, come on. Because all the life before to go from a low kind of career, like in the factories and blah, blah, blah, to the office kind of jobs to have better wages, et cetera. And I was telling him I was doing exactly the opposite.

(03:48):

So it actually took him probably three to four years before really accepting my choice. And he’s probably still a bit worried, but in now he starts to see that first I’m happy with it and second that I can kind of live out of it. To me, going to a manual kind of work is not a bad path to take. Not at all. And first, you can be very happy with it, and second, depending on the craft you choose obviously, but you can live out of it very well as well. Sometimes better than classic office kind of jobs.

Sarah Monk (04:24):

I’m wondering why knives?

Sylvain Maenhout (04:26):

It’s not like one day you wake up and you say, okay, I’m just going to change career. I didn’t even know how to build a knife before. I wasn’t into knife collecting. For a long time in my head, I said, I want to work with my hands sometimes. And it basically got more and more precise that I want to do some knives, for some reason. I believe it came from my habit of cooking. I’ve always liked the feelings of cutting, slicing when cooking. And we are both from families where you cook quite a bit. And the interest I have in using what I’m building.

Mike Axinn (05:07):

What does it mean to be a knife maker in France? So how does that fit in?

Sylvain Maenhout (05:11):

Well, that’s kind of a very interesting question because most of the time we speak of France as one of the big knife making countries. It is true somehow, but it is true on the folding knives side of things. So you will find the layers, the chair, these kind of areas where there’s a traditional building, folding knives and a bit of table cutlery. When it comes to kitchen knives, we’re not particularly good, I believe. If you want to try and make some money out of knife making, you need to go to the folding noise where you’ve got a bit like an art, some collectible kind of phenomenon with the prices going with it, et cetera. Or you can try to go to a bit on the American market like Bowie knives, like hunting knives, outdoor stuff. But when it comes to kitchen knives, your 100% on the utility market. There’s no collection.

Mike Axinn (06:20):

What was your learning curve?

Sylvain Maenhout (06:22):

Well, I guess like in all craftsmanship, it’s long. When I decided to change career, I had this chance, but I could get some finance for a training under certain conditions. So I found a three month intensive training in the south of France to learn the basics of forging and knife making. And then I came back here, went back to my previous job because what was the deal for a few months, which gave me the time to prepare the next steps. I said for at least one year, I’m not going to sell anything because I want to concentrate on learning, building my own style as well. But first of all, learning, learning, learning. There’s everything around. I mean, doing a nice looking knife is one thing, takes a bit of time to practice and get the proper gesture, et cetera, et cetera. The first year was really kind of secret work in my workshop, doing a lot of knives, throwing them away, testing, et cetera, et cetera.

(07:28):

Then the second year was a bit of started to sell a few knives, but I wasn’t 100% confident about my work. It’s very difficult as well to get some feedbacks at some point. Just because the first persons you sell to are people you know. So it’s not 100% honest, I’d say. And then because it’s a small community, knife making, especially for kitchen knives, so it’s long as well to get to know of a craftsman and get some feedbacks and blah, blah, blah. So basically you are kind of progressing blind. You don’t exactly know where you are in your learning curve, what exactly you need to improve on, et cetera, et cetera. So it takes even more time. When I started, someone from another discipline told me, well, craftmanship is a five years learning curve before doing things well. That’s where I am pretty much right now, and that’s what I feel as well. Do you want to go to the workshop?

Speaker 4 (08:28):

All right. Oh, so be careful what your head [inaudible 00:08:29].

Sarah Monk (08:28):

What a beautiful floor again, I’m a bit floor obsessed. So this is under the house. We’ve just come around the corner and gone underneath.

Sylvain Maenhout (08:47):

It’s pretty small. I used to have a much bigger workshop downtown in Paris, which was costing me a lot of money. But at least here it’s my place. So this is one part of the workshop. This is the metal working side of things. So the forging area and everything around steel working basically. This white cube here is basically the forge. Gas forge.

Sarah Monk (09:13):

So what’s that involve?

Sylvain Maenhout (09:15):

That involves just hitting up the steel, hammering it, just shaping it before going to the next steps. So we can talk later about the various ways of making a knife. Forging is one of them. Also, it opens some ways that you cannot do with all the methods. It’s just one of the things that I really wanted to do when I went to knife making was forging as well. Just wanted to start from the raw material and shape it myself instead of just removing some seal with like abrasive belt and those kind of things. So

Sarah Monk (09:47):

You’re pointing to the equipment on the right?

Sylvain Maenhout (09:48):

Yeah.

Sarah Monk (09:49):

So on the left we’ve got the forging technique, and on the right we’ve got the shaving away from metal- E.

Sylvain Maenhout (09:53):

Exactly, which is what we call stock removal. We still need this kind of machine because at some point we need to remove some steel. But the idea behind the forge is just to shape the material as much as we can. And then we’ve got a hydraulic press, the orange thing over there to just press big chunks of steel, really. And this is, how do you call, a rolling mill.

Sarah Monk (10:13):

Beautiful [inaudible 00:10:14].

Sylvain Maenhout (10:14):

Yeah. It’s from the fifties, it’s French and it’s originally for jewelry.

Mike Axinn (10:20):

Being able to forge, how does that inform your knife making craft?

Sylvain Maenhout (10:24):

Well, forging is almost philosophical kind of things. It’s not because you go to the stock removal techniques that you are doing worse knives basically, or not because you’re forging, you’re doing better knives. It’s just that you just shape the material yourself, the base material, the raw material. So it’s my idea of starting from scratch more or less. So I’m just taking a bar of steel, a piece of wood, and then I’m [inaudible 00:10:49] with a proper knife.

(10:50):

And the other thing is within the kitchen knife making, we do a lot of, what we call, sunlight constructions, which is basically a three layers kind of construction of the blade. And that can only be done with the forge. But why I do forge is really about doing it from A to Z. And that’s why I came to craftsmanship, generally speaking, is doing things. So my idea is not to take any shortcut, basically.

(11:12):

The forge is something as well, I think kind of really primitive kind of thing, which is very interesting for me. It participates to the balance within the job as well because you’ve got this boost phases in the work where you actually forge, it’s hot, it’s kind of physical, et cetera. And then you’ve got these other phases of work where it’s really minimal work, very precise into the wood carving or finish, et cetera. And that creates a balance as well in the work. And that’s something which interests me. When you don’t do the forge, I think you lose a bit of his balance because you just work on the machine and it’s not the same thing. There’s something really hypnotic about the forging process, the hot steel, this really cold hard material that you can shape as you want. It’s just a bit of magic really.

Mike Axinn (12:01):

I was going to ask you about where the magic comes.

Sylvain Maenhout (12:03):

A bit of everywhere, but it’s a long process. The magic to me comes really when you actually have finished the work, sharpened the knife and you just slice through some kind of tomato or whatever else. And the feeling that you get at this point is just wow. I mean, I love my job. Every day I’m just waking up with a smile because I know I’m going to go to my workshop. Do you want to go to the other side of the workshop?

Sarah Monk (12:28):

I would love to, but I just wanted to ask you first, if I may, about the metals, because I can see a pile of metals there. I can see some wood there.

Sylvain Maenhout (12:34):

Yeah.

Sarah Monk (12:35):

So could we just talk about the materials and where do you get them from?

Sylvain Maenhout (12:37):

Yeah, the kitchen knife making has that particular idea that you are looking for the ultimate edge, like cutting is the primary purpose of a kitchen knife. So we are looking at steels which are very high grade. So if you handle them properly, you can give them some very interesting characteristics in terms of edge cutting, retention, et cetera, et cetera. So I’m getting my steel from Germany because I’ve got a guy there who is a well known guy within the knife making world, doing some knives himself. And also he’s got this business where he actually creates some steels. There’s a lot of steels which are really interesting for cooking, high carbon grade, et cetera, et cetera. When it comes to wood, basically, so I’ve got some wood stock downstairs. I’m not using wood coming from friends or just local trees, et cetera, for two reasons.

(13:35):

First, it’s not my job to actually cut them, dry them, et cetera. I don’t have the equipment, I don’t have the skill. And then you need to dry them for years and years, which I cannot do here. I don’t have the space. And the thing as well is that my customers tend to ask for exotic woods, so which is a big area of thinking in my job as well. I’m very much environment aware, and that’s one of the things that create a lot of thinking as how can we improve that? I would like to be a bit better on the environment side of things.

(14:09):

Here is the former, how do you call that, coal room. And when we got into the house, there was still a bit of coal actually inside it. So I cleaned everything, and here’s my room where I do the heat treating, which is a big part of the knife making to give technical characteristics and the sharpening. So all the stones that you see there are Japanese wet stones to sharpen the knives.

Sarah Monk (14:35):

They’re beautiful colors. What is a wet stone made of?

Sylvain Maenhout (14:38):

Well, most of them are synthetic factory made and they’re made out of, usually it’s ceramic or corundum, but well rather ceramic. And it’s bounded with resin or cement, some kind of cement. I’ve got a few which are diamond based, and I’ve got one natural wet stone, which comes from basically a [inaudible 00:15:00] in Japan for fine finishing.

Sarah Monk (15:02):

You mentioned Japan, and I just wondered is there a influence from Japan?

Sylvain Maenhout (15:07):

Why I’ve got a Japanese influence in the shapes of the knife that I do is just because I find them much easier to use. They’re much more efficient on the cooking table basically than the French traditional shapes.

Mike Axinn (15:22):

The two countries I guess are Japan and Germany.

Sylvain Maenhout (15:25):

So Germany, a bit of France as well, as I said earlier, for some brands around cooking, Germany is a big provider of kitchen knives. And in Japan. It comes down to this very Japanese cultural thing, which is perfection. So we’ve got one task, one knife, one knife, one task. You’re not going to take a usuba which is made to slice vegetables only, to cut your meat, but that just doesn’t exist. And I like this way of seeing things. I mean, it cannot apply to everybody, to all my customers because some of them just want a versatile, easy to use knife for the daily cooking. But when you go to chefs, et cetera, and you have the opportunity to build such specialty knives, it’s just like, wow, that’s why I’m doing this job really.

Mike Axinn (16:13):

I’m interested in how this work has possibly opened you up to the world of cuisine and restaurants.

Sylvain Maenhout (16:20):

That’s very interesting because they’re asking for more technical knives, usually. They’re a bit less interested in aesthetic, much more about technical qualities. They’re not telling you I want to do everything with it. They’re interested going to tell you, well, I want to cut raw fish only for instance, or I’m just going to cut vegetable. And against everything that we could think of, especially in France, those guys most of the time have dull knives.

(16:48):

So there’s a lot to do. Many, many, many professionals don’t know how to sharpen the knives. They don’t necessarily know what a good knife is. Some of them are not using the right knives for the right thing, et cetera. So there’s a lot of learning for them as well, and education from me to them to explain them how they can benefit from having better knife, just even standard knife, but at least maintain it properly, et cetera, et cetera. So that’s not really what I expected, but that’s very interesting because that gives opportunity to share my skills, my views. I’m doing some courses in some food schools to learn them to the basics of sharpening and how to choose a knife.

Mike Axinn (17:29):

Do you ever do bespoke knives?

Sylvain Maenhout (17:31):

About 90% of my work, I’m doing bespoke. In my way of seeing my job, I want to talk with the customer. Basically I’m doing kind of high end knives. And that means as well, giving the customers the possibility to choose the materials, the wood, et cetera, et cetera. But what I need as well from a technical perspective is know how they’re going to use it. And I’m not going to do the same knife, even if we agree on the shape, a size, et cetera, I’m not going to do the same knife, choose the same steel, give the same technical characteristics to someone who wants an everyday knife for their cooking at home and they don’t sharpen it. Or to a chef or professional who will sharpen it every three days, who will use it only for one particular task, et cetera. I will adjust the technical side of things depending on how the knife will be used.

(18:22):

Usually when I do knives, I’m building batches of five to six knives just for question of production process. And I’m doing one of them is on stock so that some people who like my work and don’t want to go to an order, they can eventually fall in love with it and buy it. The other thing as well is that if you don’t do bespoke, if you only sell your knives on stock, you never talk to anybody because that’s a really very lonely work. So if I’m only just push my knives on the selling website, I’m just alone in my basement. And doesn’t make sense for me.

Sarah Monk (18:57):

These are beautiful. Can you talk us through them?

Sylvain Maenhout (19:00):

Yeah. So here we’ve got a small pairing knife, like the basic in the kitchen. So like nine, 10 centimeters to do a bit of everything like peeling, removing the head of garlic, those kind of things. The woods, which is one wood that I love is cocoa wood. So it comes from Africa and we come back to the environment kind of things that we mentioned earlier. This would be the other hand of it, it’s what we call a gyuto in the Japanese word. So it’s basically the equivalent of the chef knife in the Western Europe side of things, but it’s much taller. It’s a 20 plus centimeters from an everyday cooking perspective, and you can do pretty much everything with it. This one is what we call petty, middle size, about 14 centimeters. So it goes in the middle. And the wood used here is bog oak. Don’t know if you heard about it.

(19:49):

So actually this comes from the UK. Bog oak is, oh, it’s my favorite wood. Bog oak is in oak, which fell into bog like a couple of thousand years ago. It got into the ground basically. So it started, how do you call that?

Sarah Monk (20:05):

Fossilizing.

Sylvain Maenhout (20:06):

But obviously it’s not at the end of it. So we say it’s semi fossilized, is that correct word?

Sarah Monk (20:12):

Yes.

Sylvain Maenhout (20:12):

The time it spent with the ground gave this a lot of minerals going into the wood, especially carbon, which gives it this black color. It’s the five of the standard oak basically, except that it’s black or brown depending on the origin and the age. And this one is dated 5,000 years. And it comes from not the other side of the world. Because I work quite a lot with it, I have one supplier especially for that, and it comes from the UK in the Kent region.

Sarah Monk (20:42):

Oh yeah.

Sylvain Maenhout (20:43):

So they actually find the bog oak themself. They cut it, they dry it and the sell it.

Mike Axinn (20:49):

Do you have a signature that defines you in your knife making?

Sylvain Maenhout (20:53):

We have a maker’s mark for the jewelers. So it’s this thing here so that you need to read it that way. And I chose it so the maker’s mark is very something kind of personal, and this one is an old alchemical sign, which means the purification by the fire. And the maker’s mark comes from there.

Mike Axinn (21:14):

Is there anything about your knives that we could recognize that it’s yours?

Sylvain Maenhout (21:19):

One of the things that I’m doing which is kind of recognizable over, I’m not the only one doing it, is those faceting kind of things on the handles. And this cut at the back of the handle as well, that’s a specific angle which I’m doing on all my knives. I just did it because I found it nice and it was a good way of finishing the handle. Someone told me one day, well, I recognized your knife because of that. Some people will recognize my touch in the knives. Because you are a person with a specific sense of aesthetic, et cetera.

Mike Axinn (21:55):

You have the experience of having done something well before.

Sylvain Maenhout (21:58):

I guess when you are going to a second career, and especially when you’re going to sacrifices like the financial side of things, I just cut my wages by five or six when I change career. If it was a first career, probably I would have a different vision and maybe I would not realize as much the chance that I have to be happy in my job, to wake up on the morning with a big smile, et cetera, et cetera. So I think the passion comes from the craft itself, but also from my own path really and everything that I left when I changed career, everything that I embraced, basically. I don’t need much to live. I don’t need fancy clothes, I don’t need to go in fancy restaurants, et cetera, et cetera. So just doing what I do on a day-to-day basis, being close to my family, having some time with my kids, I mean, it’s priceless.

Sarah Monk (22:51):

It was half-term and the kids were with their grandparents, which had given Sylvain and Aurelie the chance to pop into Paris the previous night to catch a foreign film. As we were leaving, they offered to share their lunch with us, and we enjoyed the freshest of eggs, potatoes, and a salad foraged from their new garden. Back in Paris, we went to a farm to table restaurant, which Sylvain had recommended. When Mike’s steak knife bore Sylvain’s maker’s mark.

(23:15):

So thanks to Sylvain Maenhout. You can discover more about him on his website, Sylvain-m.fair, or find him on instagram @sylvain.m.coutelier. And thanks to you for listening. As with all episodes, you can find photographs of the work discussed on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, or on our new Instagram account @materiallyspeakingpodcast. If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, subscribe to our newsletter on our website and we’ll let you know when the next episode goes live.