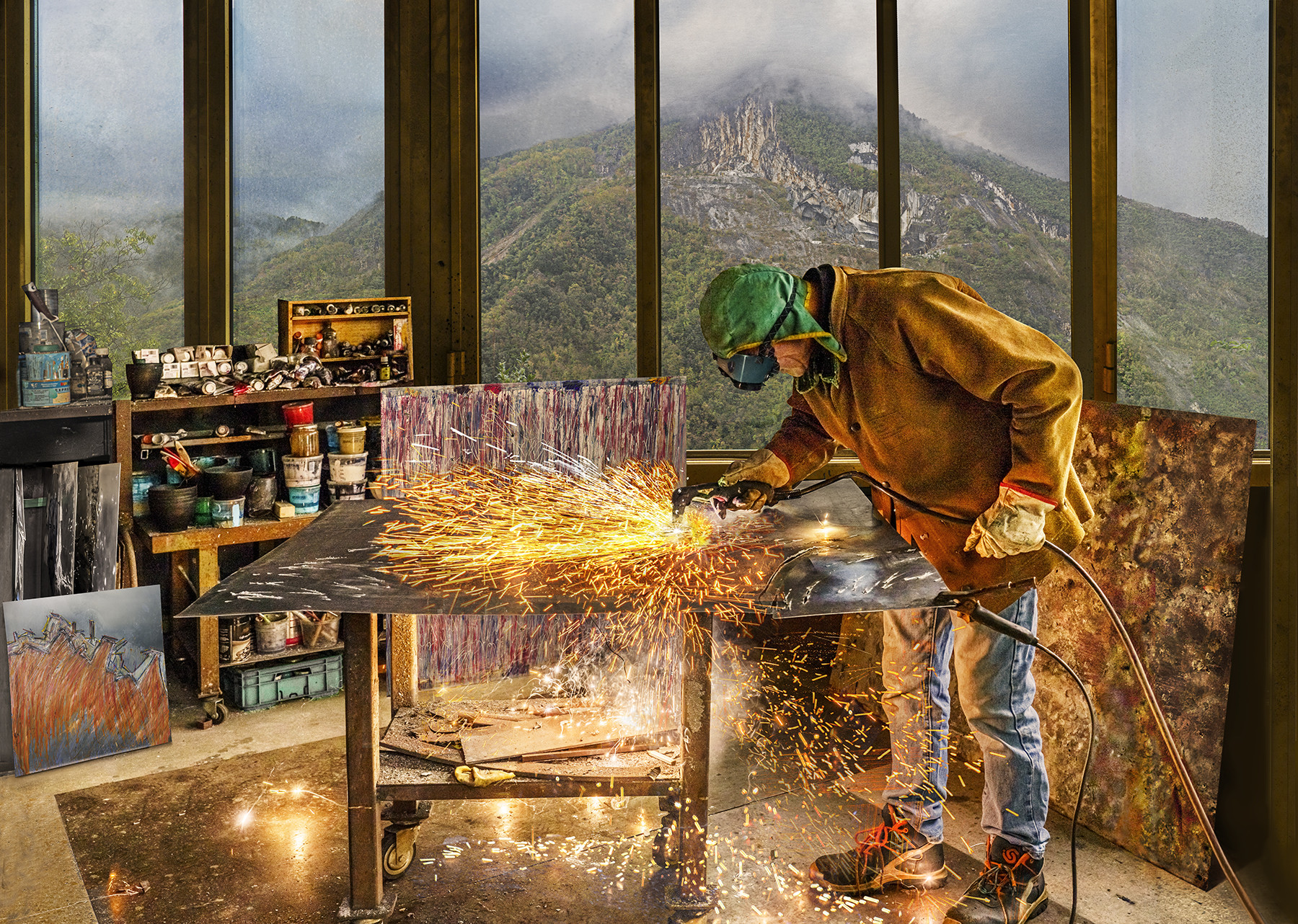

Silvano Cattaï was born in Belgium, of Italian parentage and came to be an artist in Italy by way of making films in New York. After years in sculpture he finally came back to painting, but this time with a sculptural angle, using a plasma gun and paint on aluminium.

Silvano Cattaï, 2022

Silvano’s studio houses his powerful plasma equipment and protective gear. On the walls are metal-working tools and shelves filled with tubes of oil paints. Around the studio are neatly stacked rows of aluminium sheets.

Silvano applying paint

Rack holding work on aluminium sheets

Silvano mixed his own colours and worked in sculpture in Pietrasanta for many years until he came full circle back to art, this time using the plasma torch at the same time as paint, making sweeping cuts on aluminium plates.

Silvano Cattaï, Trees, 2022, aluminium and paint on aluminium, 120 × 120 cm

When making sculpture, Silvano became dependent on other people, but coming back to painting allowed a more instinctive approach and freed him up to work by himself. Now unencumbered, Silvano finds painting provides the freedom he craved to express himself and to do what pleases him.

Silvano Cattaï, Mountain (work in progress), 2022, paint on aluminium, 120 × 120 cm

Silvano's studio and garden overlooks the mountain opposite

Silvano’s garden has myrtle bushes burgeoning with berries, persimmon, lemon and olive trees – all plump with fruit. The view is dominated by the peak of the mountain opposite, with the quarries and their familiar lines of mining scars.

Thanks to Gail Skoff for this collaboration and for the fantastic photographs of Silvano.

All photos by Gail Skoff: gailskoff.com – instagram.com/skoffupclose

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound edit and design: Mike AxinnMusic: all courtesy of Audio Network

Nico’s Arrival 3555/6, Thomas Evans

I never wanted to learn drawing, you know. That’s why I like the drawing of Giacometti. I like the etching of Goya. I like the Rembrandt, not the print, but the drawing he was doing with the ink. Modernity starts there, you know.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Mike Axon and I are meeting Silvano Cattai, who was born in Belgium of Italian parentage and came to Italy by way of New York. We drive up the winding road that weaves above Seravezza, a town lying between centuries old marble quarries and wooded mountains on the edge of the Apuan Alps. It is autumn, the trees are rich with color, and the roads carpeted with fallen leaves.

Sarah Monk:The interviewer will take us from his kitchen area to his garden studio by way of a couple of works outside. The studio houses Silvano’s powerful plasma equipment and protective gear. On the walls are metal working tools, shelves with tubes of oil paints, and around the studios are neatly stacked rows of aluminium. The view is dominated by the peak of the mountain opposite with its familiar mining scars.

Silvano Cattaï:I was born in Nerva in ‘51. My father immigrated in Belgium to work in a coal mine in the thirties. My mother, after a few years, went in Belgium and they married. I have already one sister and one brother that I didn’t know who was who died during the war. So I was named after my brother, I never knew.

Silvano Cattaï:I know very little about my father. I was eight when he died.

Sarah Monk:Does that feel odd to be named after a brother that died?

Silvano Cattaï:I think it is a little odd, yeah, because I remember when I was little, we we went to the grave, and it was my name, you know? That was Silvano Cattai. It was written on the grave, you know? It didn’t that never disturbed me too much. My childhood has been, like many people, but a little bit dramatic, you know?

Silvano Cattaï:That I understand later. Then I lost my brother when I was six, which was really one of my favorite brother. He was killed on an accident of a bike. And I saw him die. I saw him going into that thing.

Silvano Cattaï:And two years later, lost my father. And so at that point, at eight year old, I’ve lost half of my family.

Sarah Monk:I’m sorry.

Silvano Cattaï:My father was hard because there was no psychology at the time, but not in where I we’re living, and we don’t even know if they exist, you know. But they they hide the death of my father because I know what my father died. He died of cancer, but he died because he couldn’t take my brother’s death, you know, after that was something that changed my life.

Silvano Cattaï:I think maybe I had a hard time to trust people. But then, you know, it took a long time to go over that. I mean, I didn’t realize that, you know, because then my mother took care of me, and I have a brother and sister. They got married right away, so I lived with my mother practically, which was Catholic.

Silvano Cattaï:My mother has a particularity that she was a healer, as my grandmother. She could with her hand heal. She healed a lot of people, you know, from anything from the nerve, she could she could she could do that. She really thought that that’s what I should do because when I was 15, she had a clientele of twenty, twenty five people a day who come, you know, without any she didn’t ask money. She said, if you wanna give something, you give.

Silvano Cattaï:But a lot of people that’s why she maintained me for it because she she had very little pension and didn’t have money. None.

Sarah Monk:What brought you to art then? Your family weren’t artistic?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. I think I never saw a painting before I was 19 year old. Only thing that was in the in the house was a a reproduction of Monet, lingerie luis. There are people who pray in in the field, you know, the the pazen who pray in the field, but it was you a reproduction of photocopy in a frame. That’s all.

Silvano Cattaï:I think it was I almost the first time I I was acquainted with TV was I was 13 years old. There was a thing I remember in Belgium called Cine Club, you know? And that’s where I start to see all those films. They’re usually 11:00 or something like that because everybody was sleeping and I was sneaking and I was watching those films. And at that time, it was a film of Miller’s Forman or one of black and white, and start to get fascinated by this.

Silvano Cattaï:I think now I understand that I was fascinated more by the image than by the content. When I was 15, something clicked, you know? No. Even later than 15 16 when I had to work at 16 because it was the end of the study, and I wanted to study something, but I couldn’t go to school. I had to work.

Silvano Cattaï:So I did those courses, you call it correspondence, you know? But I didn’t know anything about heart, absolutely nothing. And then I worked in factory for two or three years until 19. And then at one point, I was working on the highs as an electrician, which I was. I got an accident, ping pong there, and I broke a teeth, so I went to the dentist.

Silvano Cattaï:And then I was waiting for the dentist, you know, was paid by the company. And then I see a magazine, and I see School of Film in Paris. I say, God, this is interesting. I look and say, to become an assistant director. And I was dreaming at the time, you know?

Silvano Cattaï:So I said, this is interesting. So I took the others, then I went back, and when I get to the end of my working year, you get one month, you know, to go to a holiday, pay. And at that time I decided to go to Paris and to do that school. And I went to Paris to do that with so little money that when I arrived, I paid the school half and I paid there was a small hotel, so I had one meal a day and a room on the seventh floor by foot. But I got interested in film, so I wanted to work in film.

Silvano Cattaï:And I find a place which is called NAML, there was a small TV thing. It’s actually a it was revolutionary. And so I went there because I saw that they need a reparator for TV. So I got there. By chance, I got the director, and I remember this thing too because he make me walk through this museum, which I know.

Silvano Cattaï:I mean, he say, why do you wanna repair TV? I say, well, it’s not that I wanna repair TV, but I’d like to no film, you know, because it’s for a study at that school. So he said, come back next week. And then he took me next week, and I start to work as an electrician plateau. And there was this guy, he was like 80 year old.

Silvano Cattaï:Robert Baton was his name. He was impossible. Nobody could stand him. He was, you know he had worked with, I don’t know, Rene Eclair. He wasn’t TV, but things why he’s too old, he’s too grungy, he’s too this, too this.

Silvano Cattaï:I worked with him for a year because nobody wants to work with him. I didn’t And I learned that’s where I really learned about light in film. I was 20, and he was, like, over 80, this man. Yeah. And one day, after one or two years, it happened that the call start and one camera didn’t show up.

Silvano Cattaï:So I was there, and I went behind the camera. And then at one point, and he said, camera three, because he called me camera three, and I go. And the and the director say, why? That’s a new one. He’s good.

Silvano Cattaï:And he points him, who who are you? And he say, well, that’s not a thing you should do. I said, no. But but you’re good. So I start to be able to learn to be a cameraman at that point.

Silvano Cattaï:That’s how it happened, you know. I was seeing two or three films a day and working at that time. Jean Vigo, Jean Renoir, the French New Wave, and some of the Americans. I was going to the Cinematheque in Paris. Then I became really interested in the image, and in ‘79, I decided to move to New York to change to change life, and I applied to the American Female Institute.

Sarah Monk:So you went to New York and then to Los Angeles.

Silvano Cattaï:Which is, apparently, was so difficult to enter because they were taking one foreigner on the 10. We were 40 people. The the day before me, David Lynch. It was a famous place, but I didn’t like Los Angeles. So I came back to New York.

Silvano Cattaï:I found some people because I was same thing. I was working in film, that way, to maintain myself. Then there was a period where changed, and I and I and I wanted to come back to painting sculpture, so I was doing both. And at one point, I stopped film because I it didn’t correspond to me because I said, I was good apparently, but I was doing the work of everybody else.

Sarah Monk:So you were in New York working as a cameraman, and then you fell in love?

Silvano Cattaï:I fell in love with with Allison, his sister.

Mike Axinn:Allison is my sister, and Savano is was my brother-in-law for for many years.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Because I’m not your brother-in-law anymore. Correct?

Mike Axinn:No. Ex brother-in-law.

Silvano Cattaï:I was wondering that, you know.

Sarah Monk:It’s complicated.

Silvano Cattaï:Anyway, so I really start painting, really.

Mike Axinn:I remember I was really impressed because you were mixing your own colors.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. I learned everything about the I wanted to do that. I still have the books, the bible of painting, how to make the color, aqueous oil, I still have some of those oils. It’s fantastic. Until the eighteenth century, the pigments were all natural, you know, because the sienna, red sienna is is is the ground,

Sarah Monk:you know. It’s made from terracotta, isn’t it?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Yeah. And and then you have the one from the stone, this ground, that’s all the pigment, the blue, they were all natural. You can’t invent the color. The color, the hue, the color haven’t changed for a day.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s simple, you know. The color comes from those pigments. In nature, it’s the same. You have certain blue, certain red, certain green. The cobalt blue has a hue, is pale and brilliant.

Silvano Cattaï:The Prussian blue has a hue, and ultramarine has a hue. When I was painting in the Joger, Borgen was born, you know, so I went to the center of Assar, can I keep painting with the child? And they said, yes, you can, no turpentine.

Mike Axinn:So you were painting on aluminum forty years ago?

Silvano Cattaï:I made some try because I made this this sculpture, and it was aluminum. I decided to make aluminum. That was a big project. And so I had this aluminum, and yes, I started to paint on aluminum at that time. But I didn’t do that much, because I got discouraged by the people telling me that’s not the way.

Silvano Cattaï:And now it’s funny because when I see those things now, understand that this is it works. It works.

Sarah Monk:So you came to aluminium because it was an offcut of a sculpture. Is that correct? Okay, cool.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. I did sculpture for thirty years, and I abandoned painting totally.

Sarah Monk:So when you came from New York back to Italy, or to Italy, why did you choose around here?

Silvano Cattaï:Well, I wanted to do sculpture. I had these commissions, and so I found some place. I actually went to a place between Siena and Arezzo, but when we came there, there was Lucien and Morgan, nobody was speaking Italian.

Sarah Monk:Those are your children?

Silvano Cattaï:Yes. And I listened either way, speaking Italian. So I realized that there was not possible for too much to adopt. So I had some friend that I met in New York, he said, go to Peter Santa, because at least there, there is all those people who speak English. So we came and we moved there.

Sarah Monk:Tell me about the sculpture. Was marble the attraction or not so much?

Silvano Cattaï:It was stone, yeah. But the point in my life where I am now, it kind of resembles when I came from New York to here. I mean, I was really painting in New York. I love to film. I really went into painting.

Silvano Cattaï:I think I made 500 painting. But I say it’s sculpture. I want I really want to sculpture. I did a little try in New York, it wasn’t possible. So I came here really to do sculpture, change total, which it seemed to me that what I’m doing now, the reverse.

Silvano Cattaï:After thirty years of sculpture, I said, I wanna go back to painting. And and I did I did this year.

Sarah Monk:So how what brought you back to painting, and what are you working on now?

Silvano Cattaï:I think maybe there’s something like a like in film, where I was trying to to make film, but it wasn’t possible. When I did sculpture, I had to involve all the people also. And I suddenly, after thirty years, I will still do sculpture because it’s so much of me. But I say I need I’m trying my life where my age, all my life, it has to be instinctive again, really instinctive. And the painting broad matches because, first, I do all by myself, and it’s there when it happens.

Silvano Cattaï:I’m also at liberty to say now, I don’t care if I have a style. I don’t care if I have to express or if you have to recognize, I don’t care. I just say, I wanna do a painting that I like to see, whatever. If I go in a museum or in a gallery or something, that yes. That’s all I do.

Silvano Cattaï:So for now, it’s going in in many direction, I think.

Sarah Monk:We’re not talking figurative, I’m sure?

Silvano Cattaï:Figurative come back because that’s the thing I always thought, you know. In the beginning of the painting I was doing in New York, they were were figurative, they were naive figurative in some way. But for me, it’s not a question of being figurative or abstract, because I don’t think the figurative, understand. You represent a figure of something we know and you represent, which is the story of painting. But the abstract is not abstract.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s paint, you know, because what counts in painting is not the ideology, it’s the paint. I remember that when I saw a Christ of Velasquez, I look at this thing, I remain impressed not because it was Christ, it’s because suddenly the painting of this Christ, of the painting was more powerful. Mattered. It was a Christ. The painting was so strong.

Silvano Cattaï:I couldn’t explain why, but suddenly the painting was was talking as painting. And I believe it it can still do, you know. Of course, the meantime, Duchamp, boys, the world has changed, and now also, you know, for instance, I feel closer to somebody like Kiefer than somebody like Kapoor. You know? I understand that Kiefer, I understand because Kapoor, I understand.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s brilliant, but I don’t know. I believe emotion, yeah, produce an emotion, but it’s difficult. It’s not because you make a painting, you produce an emotion.

Mike Axinn:Well, I mean, filmmakers talk about the like Tarkovsky talks about the emotion in the act of producing a movie. How does that work for you, the act of producing? You feel the emotion based on what you see on the canvas?

Silvano Cattaï:It’s essential. That’s how I do. In fact, now, I think I always worked like this. I start on something, maybe sometime rarely I say, I’m gonna maybe try to do that. So when I made those tree, of course, it was a tree because but it was from drawing I did thirty years ago.

Silvano Cattaï:But sometimes I start on something, and if something happened, then I see something coming, and there I work. But at the beginning, yeah, something has to produce an emotion. And even if I do figurative now, I work on that in an abstract way because I say, I look, I don’t think what it represents, and then maybe it becomes figurative or not. But now I don’t want to fight the figurative. So come back, but in a certain way, I think.

Silvano Cattaï:So I don’t want to fight anymore of that because I don’t have anything to prove anymore, only to myself.

Sarah Monk:So I think you had a show, didn’t you, in Cambridge?

Silvano Cattaï:Mhmm.

Sarah Monk:Recently, almost unthought? Can you tell us about that?

Silvano Cattaï:This this title came because of this working with Morgan. We we had to write a text and then then rewrote. And just just what I explain now, that those paintings, they’re not planned. I have no idea what the painting would be. It’s not premeditated.

Silvano Cattaï:No way, but it’s not even thought. I start with with the emotion, the the color, the space, and I and I found this space. The aluminum allowed me that because it’s thin, it’s light.

Sarah Monk:I was going to ask if you perhaps could explain the recent work. It’s in aluminium, so you chose the material aluminium again. But are you working with paints or plasma torch? Tell us the process.

Mike Axinn:We’ve gone outside to look at Silvano’s work with a plasma torch, which cuts into steel with a free form gesture that can resemble the work of a Jackson Pollock. I work

Silvano Cattaï:similarly with the plasma and the paint. So that that paint is is is, what do you call, electrolyzed.

Sarah Monk:It’s fabulous. It does look as though it looks so cohesive, the colors and the cuts. So when did you discover plasma torches? Because when you first started working with aluminium, it was the the paint and the reaction of the paint on the aluminium.

Silvano Cattaï:20 years ago. I was doing an exhibition in Switzerland, and I remember that I met those people, they said, don’t you come and make this exhibition in La Choutefont, which is Northern Sicilyne? And and they say, well, you you bring some stone and and bronze. And I say, but I’m not going to bring all this to Sicilyne. He said, but instead of bringing bronze, we we make it here.

Silvano Cattaï:I said, well, you make it here. And we make a foundry. But he was a little bit ingenious. And and we made a foundry. We got the material.

Silvano Cattaï:We made a foundry, and and we made those those bronze there. And the day of the exhibition, he said, something like that would be good on a a plate of steel. You know? He he showed me a plate of steel like this. He’s about it.

Silvano Cattaï:The show is tonight, and I’m not gonna have to cut this with a disc, it’s gonna have to take me two hours. He said, no. No. No. There’s this machine.

Silvano Cattaï:Said, put it machine. And he showed me plasma. So I cut the steel and put this and I say, god, that’s what I’ve been looking for.

Sarah Monk:So this was cut with plasma, the piece

Silvano Cattaï:oh No. No. No. No. The the plate of steel to put it on.

Silvano Cattaï:Okay. You know, which is what that thing, the plasma cut like this. If it I have three plasmas. If it’s powerful, it cuts, you know. And I said, this thing is incredible.

Silvano Cattaï:He said, yeah, it’s a plasma. I said, god. So what I did between the morning and the show, I made three plasmas, my first three plasmas, and I put it in the show. I sold them three pieces right away.

Sarah Monk:And it’s also sculptural, isn’t it?

Silvano Cattaï:yeah. But that was the plasma when I started is really from sculpture to painting. I made a lot of exhibition with the plasma, the steel plasma. Why the aluminum? One, because of the weight.

Silvano Cattaï:Wow. People are afraid of pieces like this, you know. This like forty, forty five kilo, that piece. Sometimes in painting it becomes totally different, it’s a sunset, you have a light. So the light is passing through. But it reflected in the medium, it’s really reflecting.

Mike Axinn:We have got this incredible view of the quarry across..

Silvano Cattaï:All the mountain. And I have to cut a little bit of this tree. But this is an incredible tree. Winter is all dead, and in a few weeks, it became that’s a lot of khaki.

Sarah Monk:I was gonna say it’s khaki, isn’t it?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah.

Mike Axinn:Alright. Let’s head down to the studio.

Silvano Cattaï:We will go down to the studio. Yeah.

Mike Axinn:Who constructed this building?

Silvano Cattaï:I did. Mhmm. And then it it was a a chicken chicken place. Yeah.

Mike Axinn:Chicken coop?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Yeah. It’s still a chicken coop. Chickens? Really Yeah.

Mike Axinn:Do you have to wear a special outfit when you’re working with plasma?

Silvano Cattaï:That’s the mask. In the beginning, I wasn’t using the mask.

Mike Axinn:It looks like like a Star Wars Like a trooper.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. It was developed in the sixties, an American invention, plasma. And I believe it was developed at the beginning because, you know, when the boat, the steel boat, when they have to take them apart, they cut the big boat, which is not more operational, to cut it in pieces to be able to reuse and refund. It’s interesting also because I developed a lot of technique with the plasma. So you have to work a certain way on the aluminum.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s extremely rapid. So you do

Sarah Monk:So it’s a quick process.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s it’s not trick. And there’s a physical, and I think I like that because I play with that, you know, that the control and not control.

Mike Axinn:You have to sort of wrestle with it?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. It’s a it’s a strong energy. I know how to use this machine now as a as a pen, as a pen on fire because you feel it, you know, it’s it’s you know, that plasma can go from 19 to 27,000 degree.

Sarah Monk:I find it interesting that your father worked in coal. Yeah. And there seems to be like a full circle a little. There’s something minerally in your father’s background and your return to sort of a mineral kind of material.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Maybe. You know, the work in the coal mine is very particular because especially in Belgium, I remember they were going at six in the morning until eight. They never saw the daylight, only on Sunday. Never seen the daylight.

Silvano Cattaï:You go in, it’s dark, and then you go in 300 meter, it’s all dark, and then you come up and it’s dark. You know? So so it’s darkness, always. Only one day you you you used to have light, you know? And for me, light is very important, yeah.

Sarah Monk:But you have said that you’ve come full circle with painting, but sort of painting and sculpture slightly combined with this work?

Silvano Cattaï:yes I think that’s what’s happening, but is it this is not a sculpture, and this is not a painting. What is it? What is it? How do you get the colors in this? When I put it, you see the color burn and then it it and some sometime now with the with the aluminum, I just do the painting.

Silvano Cattaï:It’s a it’s a new thing for me. But I don’t retouch that much when I work like this. This is heavy aluminum. It’s three millimeter, but still because this is this is like that’s also bring me liberty to work.

Sarah Monk:So can you tell us a little more about the the not naming of your pieces? What what do you do in a way?

Silvano Cattaï:You I never name it because I thought that naming it was giving a direction that they don’t necessarily have.

Mike Axinn:So do you have some favorites?

Silvano Cattaï:No. But I show you a very fair figurative painting. I wanted to do it this time.

Silvano Cattaï:But see, for instance, this because also the idea that I have of trees.

Sarah Monk:I was just thinking that the roots are as as prominent here as the trees above the ground.

Silvano Cattaï:Figurative painting. When I was in New York, I did a lot of trees. I always liked trees, but I was working in already in that direction. I used the dripping of the tree. I have to find the the right composition and the tree was forming itself, you know.

Silvano Cattaï:And I don’t think I I never take an image and try to to do it. More important is the painting than the the trees. So it’s the act of painting. Yeah. And and it has to talk as a painting, not as an image of a painting for me.

Sarah Monk:Is there anything that you’re inspired by?

Silvano Cattaï:Life is interesting. Yeah. I love tree. I planted more than hundred trees here in this place, you know. I have to stop because there’s no more room.

Silvano Cattaï:Of course, I love nature. Cities, now I can live in cities more, but I like to go to cities, I wouldn’t like to live there. Have no sense. But, yeah, nature is nature is us, you know. It’s the only thing we have.

Sarah Monk:Where do you call home? Is this home now?

Silvano Cattaï:Oh, it’s here, yeah. This is this is home. I don’t know if I call it. This is I’m not going anywhere. Don’t even know if I wanna travel in the world, you know, to go there or there.

Silvano Cattaï:I did travel doing sculpture, know. I went to Africa, Asia, China, Taiwan, Korea. I went Morocco, went in Fossil, I went in Mauritania, doing this symposium of sculpture when I was younger. I think I like to travel all this, because my way of traveling.

Mike Axinn:Travel by making art?

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Because that’s what I’m looking, something that I haven’t seen or they have seen, but that I never really seen.

Sarah Monk:Do you work in series?

Silvano Cattaï:My work has no sense if you see one painting. You have to see 10 together and then then maybe there’s a there’s a story. There’s something.

Sarah Monk:Did you say the colors change over time?

Silvano Cattaï:It needs some time, four or five months to dry.

Mike Axinn:That one is just kind of a light touch with the with the plasma.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. Almost like an aqua.

Sarah Monk:Oh, that’s beautiful.

Mike Axinn:How do you get a straight line with plasma?

Silvano Cattaï:Do I have to say all my tricks? haha

Sarah Monk:This kind of for me looks like the body of mountains opposite.

Silvano Cattaï:Lately, I something that’s always been my work in New York is landscape. I like some something of the landscape. So I did the whole things that became landscape.

Mike Axinn:So this one has, is it oil? It looks like there’s almost a wateriness to the drip?

Silvano Cattaï:It’s oil. Yeah. Very very dilute. Dilute oil.

Mike Axinn:Yeah. And above the the painting is is kind of radiating.

Silvano Cattaï:This is a bit a bit of of the tree, of the bush. And I why I put this line there? I don’t know. But I thought that it needed there.

Sarah Monk:It’s a little like with the tree that you have a line and below the earth level and above the earth level.

Silvano Cattaï:At the beginning, I used to call this a quarrel, this painting I did, but now it’s become more painting, I think. I don’t know if this one works, but I think I decided I leave it like this.

Sarah Monk:I like it very much.

Mike Axinn:It’s beautiful.

Sarah Monk:So do you find it difficult to finish paintings? Do you like revisiting them and working on them? Or do you know Do you find it easy to know when they’re done?

Silvano Cattaï:It’s just I should see it. If it’s there, it’s there. So this could be there, but I’m not sure it’s there. And yet it’s not so bad and they haven’t talked to me, I don’t know. I never want to learn drawing, know.

Silvano Cattaï:That’s why I like the drawing of Giacometti, I like the etching of Goya, I like the the Rembrandt. Not the not the print, but the the the drawing he was doing with the ink. Modernity start there, you know. It’s a brush and ting ting, but it doesn’t make a figure and there’s two line, you know, or something, but they’re right.

Mike Axinn:I was so interested when you said you did symposiums in Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

Silvano Cattaï:I did a symposium in China, in Gulen, and that’s 1999. And then I came directly from China because I was going to to the symposium, even not stopping to Italy. To I don’t know, it’s the capital of Mauritania now. In China, you went across the street, didn’t know what to do because it never stopped the people. Was incredible.

Silvano Cattaï:When I arrived in Sahara, nothing. Not a building, not a tree, not a bird, nothing. Nothing. Absolutely. The silence, phew.

Silvano Cattaï:Yeah. And just the wind, which moved the sand, was incredible. There I realized that what comes is that if you breathe, eat something and the rest have no importance because if you walk and you die, simply. And nothing is important around you.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to Silvano Cattai. You can see his work on his website, cattai.net, or on Instagram @_cattai_s . We are lucky enough to have Gail skoff’s amazing photographs of Silvano on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, on Instagram. You can also check out more of Gail’s work on her website, gaileskoff.com, and of course on Instagram, skoffupclose. And thanks for listening.

Sarah Monk:If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, subscribe to our newsletter on our website, so we can let you know when the next episode goes live.