Ron Mehlman in his studio, Pietrasanta, 2022. Photo: Benvenuto Saba

Ron Mehlman grew up in Brooklyn and came to Pietrasanta in the 1980s. In his quest for creating sculpture infused with spirit and life, no materials are off limits.

Ron Mehlman, In Retrospect exhibition, 2021

As we settle down to talk by the warmth of his log-burning stove, Ron describes the two walls of his studio with their alphabet of colourful abstract sculptures – created from stone, wood and bronze – each one perched on its own individual shelf. The project started as a way of making thin sketches out of the stones available in the area.

Ron talks about his family from the Ukraine, his neighbourhood and his upbringing in New York. He tells of his student days, his teaching work and how he originally came to Pietrasanta with Janice, a photographer, now his wife.

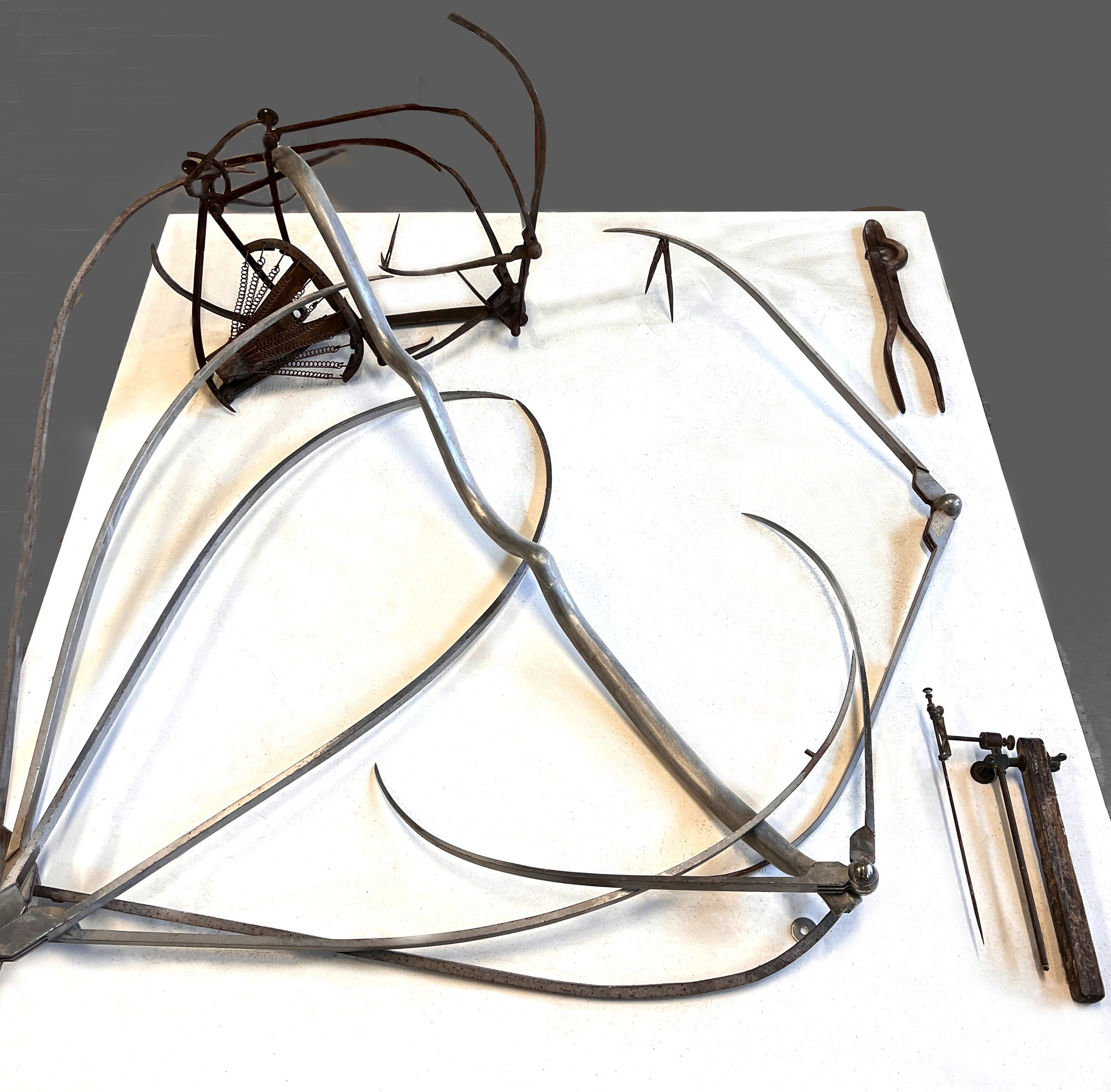

Ron Mehlman, Drawing in Space. Photo: Janice Mehlman

Ron discusses an abstract metal piece called Drawing in Space. It reflects his upbringing in New York where he salvaged scrap to use in his art. This three dimensional assemblage is created from parts of tools used to copy a marble sculpture, as well as an old bicycle seat.

Ron Mehlman, Painted Mountain. Photo: Janice Mehlman

He also spoke about a work created from a stone which he fell in love with that reminded him of an intricate, Chinese drawing of a landscape. He bought the broken stone, put it together and carved a landscape in front and behind it.

Ron Mehlman, Leaves of Glass. Photo: Janice Mehlman

Many of Ron’s sculptures play with light which he employs in order to reveal the geological formations and intrinsic natural beauty of the stone he works with.

Ron Mehlman, Life in its Shell. Photo: Janice Mehlman

Ron Mehlman, Layered Mountain. Photo: Janice Mehlman

Ron shares his home on the edge of town with his wife the photographer Janice Mehlman – instagram.com/janicemehlman. It’s a pretty house on the hillside, with neat rows of vines below it and a stone studio with high glass windows set in the garden. The studio is surrounded by sculptures and stacks of stone waiting to be worked.

Ron Mehlman, 2022. Photo: Federico Gherardi

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Hipster Pockets 3 3536/50, Jason Rebello

I really see myself as a New York artist with a unique contemporary vision. I choose to spend a lot of my time in Italy, and with it comes all its history and traditions. I try to infuse my work with light, color, and atmosphere. It’s sometimes easier said than done. The materials I work with are primarily stone, glass, wood, bronze, and various contemporary resins.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of materially speaking, where artists tell their stories through the materials they choose. I remember seeing today’s interviewee, Ron Mehlman, when I first arrived in the Piazza Of Pietrasanta 13 Years ago. He was a big presence with an open demeanour and a ready smile. And I soon learnt that he was a prominent New York sculptor and part of the wave of artists who arrived here in the nineteen eighties.

Sarah Monk:However, like so many in the community here, our lives were close but not overlapping until Mike Axinn and I arranged to meet him at his studio. Ron shares his home on the edge of town with his wife, the photographer, Janice Mehlman. Inside, the studio is light and modern with workbenches heaving with a wide range of tools and glue, ready to work every type of material. On two walls are an alphabet of colorful abstract sculptures created from stone, wood and bronze, each perched on their own individual shelf. We asked Ron to introduce himself.

Ron Mehlman:My name is Ron Mehlman. I’m a sculptor originally out of Brooklyn, New York. I consider myself a New Yorker and not necessarily an American American. I consider myself a New Yorker. A New Yorker is more international, deals with many different kinds of people, and has various cultures which one can become interested in and follow through.

Ron Mehlman:So we have so many museums, so many music halls, so many places, which we don’t necessarily take advantage of everything, but it’s kind of wonderful to have all that at your fingertips.

Sarah Monk:So where are we now?

Ron Mehlman:We are currently in my Italian studio, which is cut into the hillside just above the town of Pietrasanta It also has a beautiful view of the Mediterranean. The property has enough woods around it, to have a sculpture park. And slowly, we have cleared away some land and have put some sculptures which seem to go into this place very beautifully. In my studio, on two large walls, is a wall relief composed of 80 smallish sculptures.

Ron Mehlman:And I used material that I found in and around my studio. There are about 80 sculptures that is really made into one sculpture. This project really started as me trying to make individual sculptures or sketches for sculptures. And it developed from that idea into this monumental piece. People, when they look at this project, all 80 pieces, describe this to me as a project that feels like hieroglyphs or maybe an ancient new alphabet or seemingly creating a new language altogether.

Ron Mehlman:And how these sculptures begin, they’re made of stone generally with some wood elements and some bronze elements. They’re abstract, all of them, and they’re made of all different kinds of stone cut thin, so they’re not blocks of stone. And they’re kind of light, so that maybe eight pounds is maximum weight of any of them. And they’re all glued and pinned together, and they’re placed on a a piece of steel which attaches to another piece of steel which is screwed into the wall. The whole project started not as a the piece that you see on the wall here, but it started as a way of making thin sketches for what I was doing in the stones that are available to me.

Sarah Monk:Can we just touch on your childhood and your family? The very first time that you were drawn to art.

Ron Mehlman:Working class family. Rarely saw my dad because he had so many jobs just to provide enough food for my table. I had a sister who was ten years older than me. I was obviously a a mistake because we had no money, and it was just at the end I was born just at the end of the Great Depression. Now my parents, they came from The Ukraine.

Ron Mehlman:I’m first generation. They came as children to America. And they both of them, my parents, never went to school. But they taught themselves to read and write. My father never newspaper from cover to cover every day.

Ron Mehlman:And my mother would do things like listen to opera on Sunday. Growing up in Brighton Beach, we’re working class Jewish neighborhood with Italian surrounding our neighborhoods. Every time you have a Jewish neighborhood, you always have an adjacent Italian neighborhood. New York’s very interesting to me. I had a wonderful high school, wonderful art department with a full time sculpture teacher, high school.

Ron Mehlman:I got involved in little wood things and so forth. And then I asked him, I said, you know, this is I love to do this stuff. Do you think I could be a sculptor when I grow? And he, being another teacher, wonderful man, high Freilisher, I’ll never forget him. He said, you know, Ron, sculptors don’t make a lot of money.

Ron Mehlman:And if I were you because of you love designing, I would study industrial design. My mother’s idea was that my sister and I would go to the university, and that was our way of getting out of where we were. And I did not go to college. I could probably because I was a runner and a fairly good, not wonderful as I found out in college, but a good, fast kid. I got a scholarship at the University of Illinois to study industrial design, which you had to study art for the first year as a basic course.

Ron Mehlman:I loved it. And I also won a prize in those years as a sculptor. Anyway, at the end of that year, I had a automobile accident, couldn’t go back for my final year. And I went to the Art Students League, which is a school in New York City, which is a wonderful school. You just can go anytime and you join a class, and you jump in the class, and you start anytime you come in.

Ron Mehlman:And I met my teacher, Nat Kass, and he looked at me, and within a week, he made me his assistant in the class. I used to go to bars with my friends for a beer after work. And one of the bars I went to was Max’s Kansas City, but that’s another story. My bar experience as a young artist was fantastic. We would go to the Cedar Bar on University Place where I noticed that all the most important artists of the time were drinking and or arguing and most of the time doing both.

Ron Mehlman:Most drank a lot in those days. Many of them had just returned from a nearby club meeting. The meeting was held in one of the offices of New York University, which was nearby. The club president was a sculptor named Philip Pavia. Years later, Janice and I met Philip Pavia in Pietrasanta where he maintained an apartment, he spent a lot of time doing sculpture here.

Ron Mehlman:What an amazing gift it was to be a young artist in the sixties in New York City and meet with all these fabulous creative artists of the time. Artists I was reading about just a few months before, just an art magazine. Here I was drinking across a table with them, And they were telling me the stories and their philosophies and their wants and their problems, and you could do it face to face. It was fantastic. In time, I met artists at the bar, Sylvia Stone, who later became a colleague, Al Held, David Smith, great American artist, and, his wife Dorothy Dana.

Ron Mehlman:David Smith had recently bought a fabulous new studio at Upstate New York. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, who would go to the Cedar Bar, not often, but they went, were now spending more time in the Hamptons where they bought a house in Springs. In New York, we don’t have lot of blocks of marble lying in the neighborhood like it is here. In New York, we have trees, which I can go Upstate New York and go to a a yard, a wood yard, and buy a tree and not cut it up and then take the tree back to Brooklyn and bring it to my studio there. So I would find an oak tree or various kinds of tree, all hardwoods.

Ron Mehlman:I don’t know why I did that, and carve it and break it down into a sculpture. I knew that inside that tree was my sculpture, and all I had to do was release it. I did pretty well with my wood sculptures for a number of years. After about twenty years or so working that way, I decided to expand my horizons and to look for something else, to look for a new way of seeing, a new way of thinking about my sculpture and how to expand my horizons. So I decided instead of using a dense material, to use a translucent material.

Ron Mehlman:Instead of using a heavy material, use a light material. Work with opposites. I added plexiglass to my arsenal. I added various kinds of meshes, bronze mesh and aluminum mesh, all with different colors, and tried to integrate them into the work that I was trying to do at that time. And I got away from the idea of carving a sculpture, but building a sculpture.

Ron Mehlman:In 1970, I bought a ruin of an old carriage house in Brooklyn. The building which excited me when I first saw it because it had all the potential for a a sculpture studio, Big doors to get into the front. I could drive a car in. Second Floor was a beautiful open space for living, and it was very cheap because neighborhood wasn’t what considered upscale. I hired two young artists at the time.

Ron Mehlman:I was teaching also. I spent two years building this studio with these two young men helping me. One of these students was a young sculptor who became a friend and who had spent time in Pietrasanta and would constantly talk to me about this great place for sculptors. Then a few years later, I met Janice, and we decided to take a trip together in 1979. I said, I’d like to go to Italy, Pietrasanta, because Jerry Siciliano has been telling me about this sculptor’s town.

Ron Mehlman:So we went to a week in Rome, and then we got on the train, and we came to Pietrasanta, It was because of Jerry’s urging that we came here. We rented a house for $80 a month or something like that up in Capizano Monte. It had no bathtub or shower, but everything else was intact. The kitchen was intact, the bedroom, that’s all you need, really.

Ron Mehlman:You can go dirty for three months, but it was but we looked down at the sea and the town below, and I said, oh my god, we are in heaven. Our first day in Pietrasanta driving through the town, I said, we don’t know anybody. It’s great. Just the two of us together. And I see across the piazza my old teacher.

Ron Mehlman:So I say, Nat. Nat cares. Nat, how are you? That’s, you know, great to see you. What are you doing here?

Ron Mehlman:He said, well, I have a a studio here. He said, you should get a studio here. I said, I just got here, you know. No. You’re love it here.

Ron Mehlman:Well, the truth is we fell in love with this town immediately. We just loved it here. We loved the people. We loved the idea that they’re mostly working artists. We loved the idea that the people were so sophisticated and sweet in general.

Mike Axinn:When you got to Pietrasanta, you were not working in stone.

Ron Mehlman:No. I wasn’t working in stone. But then you get here, and that’s the local building material. That’s your material. And it’s cheap, and it’s beautiful, and why not take advantage?

Ron Mehlman:So I went back to Brooklyn, I started thinking about how can I develop my work and work in a way that was different than the usual Pietrasanta white marble stuff? And used as if you’re cutting out paper of various colors and various textures and putting them together. How could I do the same thing with stone? I noticed all these stones from all over the world that one can buy in the marble yards around here because what Pietrasanta and Carrara and all these areas are importing centers. So I was attracted to that, rather than as just carving white marble, which the old story is that the sculpture is embedded inside the stone, and they are going to release it.

Ron Mehlman:And it’s a wonderful way of thinking, and it’s an ancient way of thinking, and much to be respected.

Mike Axinn:Talk a little bit about the lifestyle you have of moving back and forth between those neighborhoods in Pietrasanta?

Ron Mehlman:It’s completely different, and you have to change your mindset. Here, my life was rural. Here, I have friendships, deep friendships because of a natural interest in art and sculpture. That’s one kind of life. My life in Brooklyn, in a neighborhood which has become upscale, I’ve been living on that block for over fifty years.

Ron Mehlman:To be a serious artist in New York is a little different than being a serious artist in Pietrasanta. In that, being a New York person, I’m not afraid to skip around and use a part of an old chair to make a sculpture or something you find on the street or a mechanical part of a car interesting that I could use in the sculpture. It’s all part of making form and developing form.

Mike Axinn:I think of Picasso and the bicycle handlebars and seat turning into a bull.

Ron Mehlman:Exactly. And if you turn around here, you’ll notice there’s an abstract sculpture here on the ground. And on this sculpture, which is all made of parts used to copy a marble sculpture. These are all parts of the tools that one makes a marble sculpture. And right there is a bicycle seat.

Ron Mehlman:So right there in the center of that piece. So that question was very good. I love that question.

Mike Axinn:You can see the animal kind of rising up out of that, an interesting and almost mythical animal.

Sarah Monk:So they’re all metals. This work

Sarah Monk:is all in different types of metal.

Ron Mehlman:Yeah. And the idea was to make a drawing, a three-dimensional drawing, in metal using parts that make in which an artisan would use to copy a sculpture. What you see here are a sculpture drawing, a composition made of tools. Some are handmade calipers. Some are new.

Ron Mehlman:Some are antique. I worked all of these tools into a composition which becomes a three-dimensional low relief sculpture.

Mike Axinn:You’ve got these incredible sculptures that combine different materials, and it has this feel like mountains and clouds. Can you talk about those a little bit?

Ron Mehlman:I think I got the idea from just watching the sunsets from my property, from my hillside, and watching the various colors at various times of the year. If you look out over at the sunsets, there are some hills and mountains in the background. And it came to me that I could use that kind of feeling, using mountains to build a a base for a sculpture, and then using other stones like onyxes to give the feeling of lightness and clouds floating by the islands or the mountains.

Mike Axinn:I’m also thinking of the piece outside where it’s a stone and it looks like a Japanese wood carving.

Ron Mehlman:The stone right here, well well, I thought of it as Chinese. It has the feeling of a intricate Chinese drawing of a landscape. So perfect that when I saw it, I was dazzled. And I bought that stone. It was in pieces, and I bought it and immediately tried to put together something that made it better.

Mike Axinn:It’s a little bit back to your adage about releasing the piece from the stone.

Ron Mehlman:Yes. Except this was completed inside the stone. It was all there. The whole piece was there. I didn’t have to touch it.

Ron Mehlman:But I did add a landscape. I carved the landscape in front and a landscape in back to hold it vertical. This was a very thin slab, two centimeter slab. And to add some color to not that stone, but to the stone around it so it kind of melds together with the original brown onyx. It’s an onyx.

Ron Mehlman:I wish I could find it.

Mike Axinn:So what does this tell us about the work of Ron Mehlman?

Ron Mehlman:It tells us a little bit about Ron Mehlman in that he’s willing to take chances with pieces that haven’t been explored before. I think of myself sometimes as more of a designer than a sculptor because if I see an idea that exists, as I’m looking at it, and I say, you know, I could do something with that. If I see a space and I wanna fill it, I can design for that space. It’s a big negative space in front of a building and so forth. How do you make that space work for you as the as the sculptor rather than how can I fit my sculpture into that space?

Ron Mehlman:How can I design a piece for that space? My biggest sculpture is in the center of Manhattan. It’s on 50 First Street between Park and Madison. I got that commission in a competition. And among those in the competition was one of my great heroes, and who later became a friend of mine because he also worked here, Issamu Noguchi.

Ron Mehlman:And I made a a model in three or four days of wood, and I included glass instead of water in the model. And I brought the model in. And then I asked the people who were in charge of the project, who were the other artists involved? Well, Noguchi. And I said, well, that’s that.

Ron Mehlman:You know, an artist with that kind of reputation is, I’m out of here. A few days later, I get a phone call from the people running the building, and they said, you won the competition, and we expect you to work on this and and so forth. I was very happy to have beaten one of my heroes.

Mike Axinn:Who were your major influences? You mentioned Noguchi.

Ron Mehlman:Before there was a Noguchi, there was a Brancusi. I discovered Brancusi early on, who was really a working class guy from Romania and was able to come up with all these great inventions, great craftsman. And he became an early hero. Also I discovered at that time Henry Moore. And so early on, I guess you can call me little Henry Moore ish and a little Brancusi ish.

Ron Mehlman:And I also was influenced by Arp because he was easy. You know, his forms are so inviting and smooth and true. And then along the way, you know, you pick up other heroes.

Sarah Monk:Do you have any advice for your younger self?

Ron Mehlman:What a good question. I was a professor of art for about thirty years at Brooklyn College because it gave me all the time in the world to make my sculpture. And it gave me food on my table. So it was a gift teaching. If I were to take advice from this ancient Ron Mehlman, I would do the following.

Ron Mehlman:I would show my work at every opportunity. I would not hold my work back for anything and for anybody. I would get my work out there as soon as possible so I could develop my art in the public domain. If I were starting now, I would adjust my feelings about getting my work out there. That would be the big change.

Sarah Monk:And what are you working on now?

Ron Mehlman:My newest series is called Back to the Future. It’s about embracing for me what is new technology. I began this process by scanning older works and reinventing them and then carving them with a computerized robot. After that, I began using a three d printer, and I’m now doing a whole new series based on my old wood carvings. How I did this, I looked into my dead storage area in my studio, a place which I hadn’t looked at in years, and found all these sculptures covered in cobwebs and making wholly new works translated with this new eye.

Ron Mehlman:Some of the pieces have added color. Some of those pieces were white like marble. So I started to work in this way in which I was able to take what could be heavy sculptures, make them in Styrofoam, coat them so they become more solid with resin, strong material, and still, at the same time, something that might be two tons can be lifted by two people and put into position. I have been so far exhibiting them in Italy. I have a number of pieces now in Pietrasanta in a show, and I had them exhibited in Florence at Aria Art Gallery about five months ago.

Ron Mehlman:It’s hard to be an artist and keep fresh all the time. It’s like keeping your youth all the time. For me, it’s exciting to continue to move forward and onward. And here, I’m actually looking backward to go forward.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to Ron Mehlman. You can see his work on his website, ronmehlman.org, or on Instagram @ronmehlman. As always, you can find photographs of the work discussed today on our website materiallyspeaking.com and on Instagram at materially speaking podcast. Thanks for listening. And if you’re enjoying materially speaking, please subscribe to our newsletter on our website so we can let you know when the next episode goes live.