On 15th April, 2019 a catastrophic fire broke out in Notre Dame Cathedral. Parisians watched in horror as the spire fell and most of the roof was destroyed. In the aftermath it became clear that a large area was contaminated with toxic dust and lead.

The iconic building, which has dominated the Île de la Cité island in Paris since the Middle Ages, is a national symbol not only for the French but for people all over the world.

President Macron pledged to build back the cathedral as it was before, and as the planned reopening in December 2024 looms, a huge office structure has mushroomed around it and 500 workers are on site daily as the team race to rebuild it.

The eyes of the world are watching, but Materially Speaking has a story for our ears - the story of its sound.

As a sound specialist himself, Mike Axinn was fascinated when he discovered there is a group exploring the restoration of the acoustics at Notre Dame. He approached Brian F.G. Katz and David Poirier-Quinot at the Sorbonne, and their colleague, sound archeologist Mylène Pardoen, who is co-coordinator with Brian of the scientific acoustics team assisting the reconstruction of Notre Dame, and soon we were off to Paris to hear their stories. We first met Brian and David at a restaurant and then visited their simulator inside the Sorbonne to discover more.

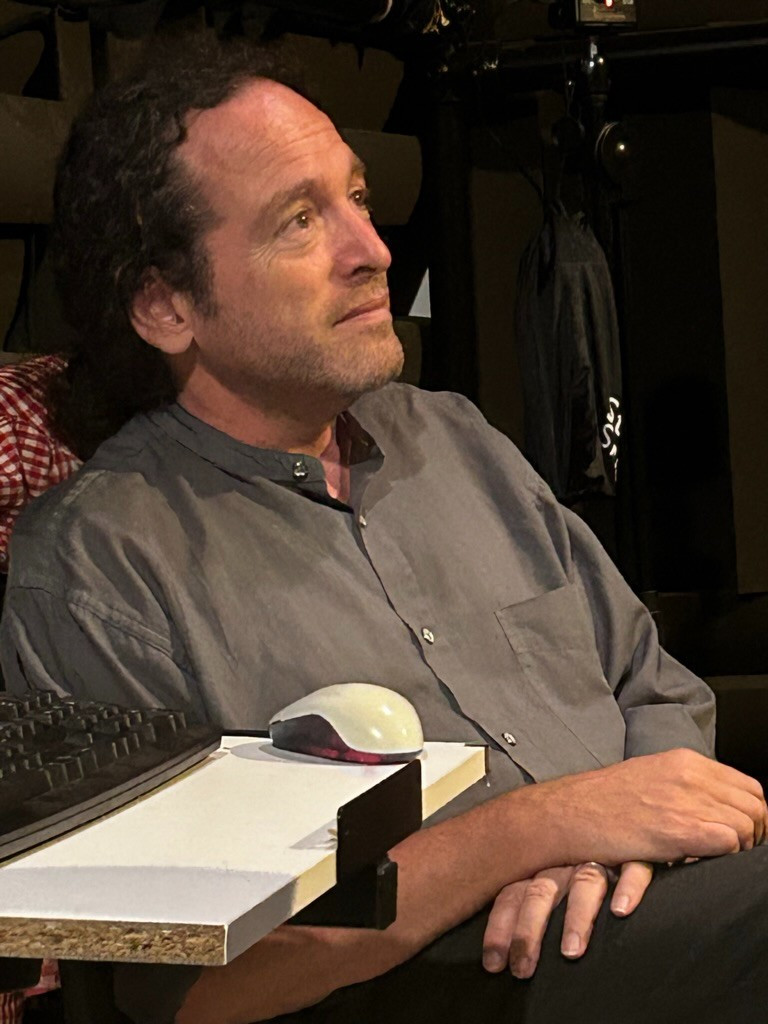

Brian F.G. Katz, acoustician

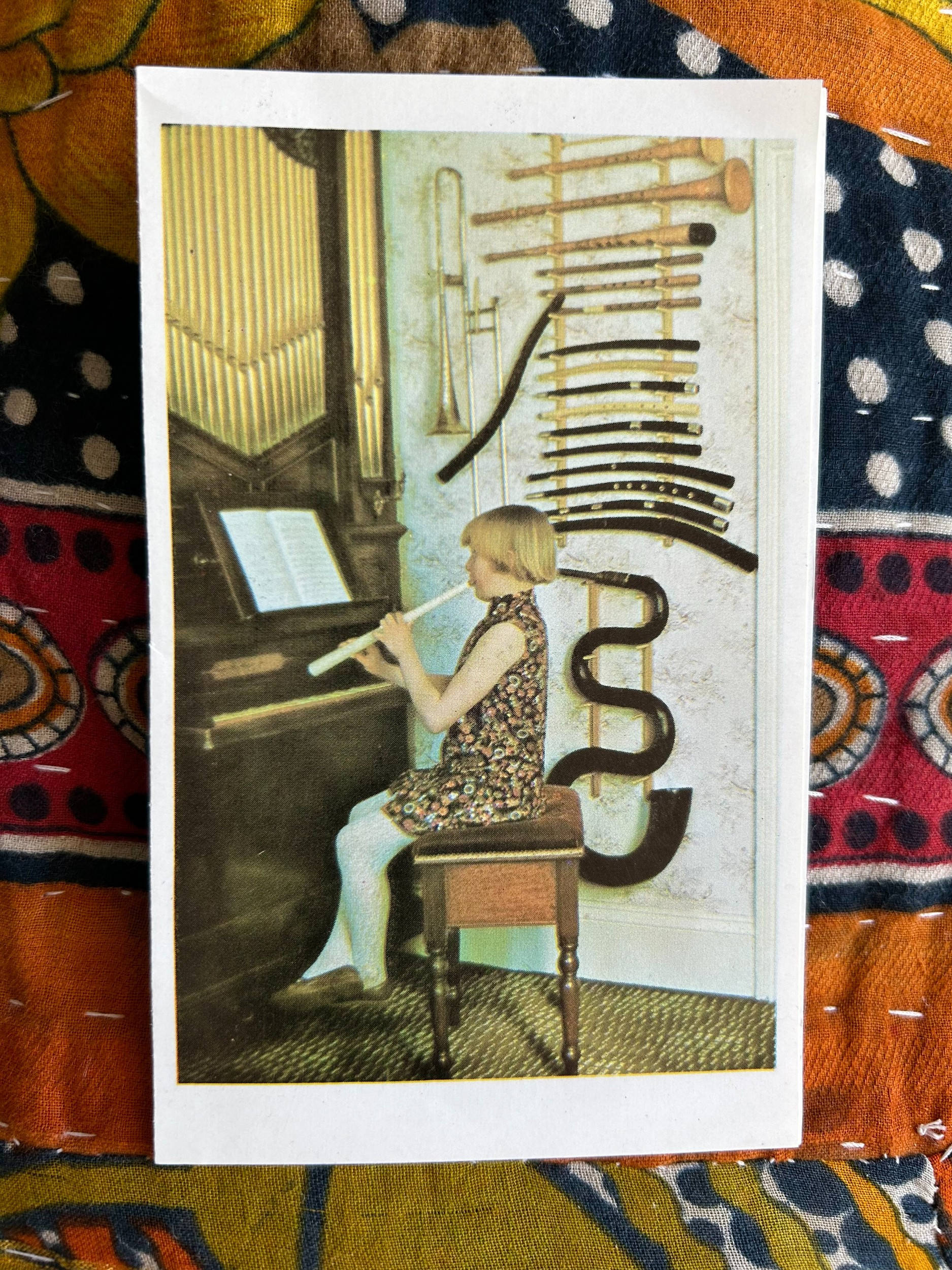

Notre Dame has a special role in western European music’s history and is generally thought of as the cradle of polyphony. Sarah was attracted to this angle as her father, Christopher Monk, was part of the Early Music movement which restored the use of the Renaissance cornett, a woodwind instrument well known in Monteverdi’s music. He also made and played serpents, long snake-shaped instruments that had a central role in music that was performed in Notre Dame many centuries ago. So she approached Volny Hostiou, one of France’s leading serpent players, and we were delighted when he and singer Thomas Van Essen agreed to join us in Paris for some experiments with Brian and David.

Thomas, Volny and David (from left)

Thomas Van Essen and Volny Hostiou (from left)

Volny Hostiou

We then jumped on a train to Lyon to meet with Mylène Pardoen and learn more about her work as one of the world’s foremost sound archaeologists, tasked with recording the sounds made by stone masons and other artisans in their work, and re-imagining the church’s soundscape at various points in its history.

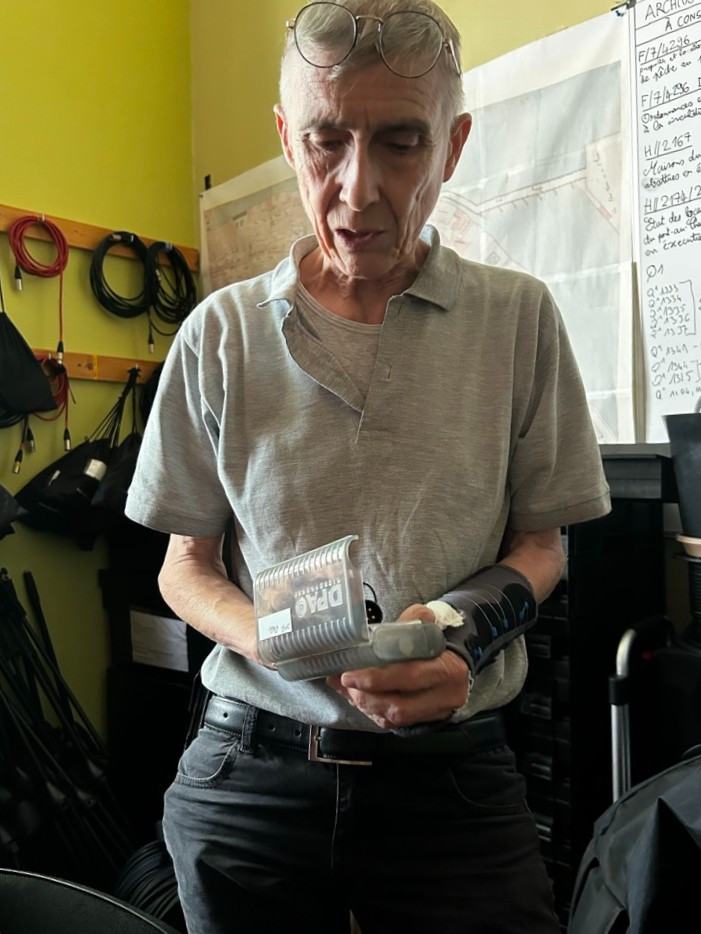

Mylène Pardoen in her studio

A key person driving the physical restoration is Pascal Prunet, Chief architect of historic monuments in France and part of the team in charge of restoring Notre-Dame. Prunet explains that their work in restoring the church has revealed many secrets about its construction and the work done by artisans. We were fortunate to hear how his team was able to discover things they never would have learned had it not been for the fire.

Fire damage at Notre-Dame cathedral

As we obviously could not go inside Notre-Dame, Volny and Thomas then kindly arranged for us to hear them play in the Abbey of Rouen, built on a similar scale to nearby Rouen Cathedral, the abbey is famous for both its architecture and its large, unaltered Cavaillé-Coll organ. Here they talked to us about the serpent and their group Les Meslanges, showed us a serpent fresco on the ceiling of the Abbey and played in three different locations.

Fresco of a serpent at Rouen Cathedral

Thomas & Volny in Rouen Cathedral

Finally Mike takes us back to Brian and David’s simulator to compare and contrast the sound of the musicians live in the Abbey of Rouen, and their simulated version of how the music would sound at different historical periods of Notre-Dame’s history.

Sarah as a child playing a cornett

Thanks also to Frédéric Ménissier who made a great video recording of our visit to the Abbaye of Rouen. Watch out on social media during the re-opening of Notre Dame to see snippets of Volny and Thomas playing the serpent play in Rouen.

Thanks and links

We are very grateful to Brian, David, Mylène, Pascal, Volny and Thomas for giving so generously of their time and sharing their expertise and passion. You can learn more about their projects in the following links.

Brian F.G. Katz & David Poirier-Quinot

Brian Katz, originally from the U.S., is an acoustics specialist and leads the Sound Spaces research team. David Poirier-Quinot works with Brian and is a researcher, presently focused on sound spatialisation, perception, and room acoustics simulation for virtual and augmented realities.

Brian's team has also launched several exciting audio projects in conjunction with the reopening of Notre Dame, entitled The Past Has Ears.

Looking For Notre Dame, featuring a radio-fiction in 4 parts that weaves authentic recordings into a fictional tale about Victor Hugo and writer’s block, available in French and English.

Notre Dame Whispers, a personified audio-guide of Notre-Dame, exploring the (sonic) history of the building, available either on-site with GPS tracking or remote without, available in French, English and Spanish.

Vaulted Harmonies (launching January 2025), an “archeoconcert”, presenting the musical history of Notre-Dame through 11 musical pieces spanning 8 centuries, each rendered in the acoustic of the period, interlaced with 3d renderings, and brief explanations of musicological, architectural, or historical information, available in French and English.

Mylène Pardoen

Musicologist and soundscape archaeologist Mylène records and recreates the sounds of the past. She is a scientific expert for the restoration of Notre-Dame - Co-coordinator of the Acoustics group. She is also designer, coordinator and manager of the Bretez and ESPHAISTOSS projects.

Pascal Prunet

Chief architect of Historic Monuments responsible for the restoration of Notre-Dame de Paris is noted for his work in the restoration of the Cathedrals of Paris, Nantes, Limoges, Nîmes, Arras and Cambrai, as well as the Opéra Garnier in Paris , Le Corbusier 's Villa Savoye and the Citadel of Lille.

Volny Hostiou & Thomas Van Essen

Musicians specialising in performing compositions that were written for, and often performed for the first time in, Notre-Dame.

Volny teaches tuba and serpent at the Rouen Conservatoire and creates projects in collaboration with the Musée de la Musique de Paris.

Thomas is a musicologist, flautist and singer, dedicated to early music and founded Les Meslanges, one of the early music ensembles Volny plays in.

Les Meslanges is supported by the French Ministry of Culture, the Regional Arts Council of Normandy, the Normandy Regional Government and the Rouen City Council. The ensemble is a member of FEVIS – the Federation of Specialised Vocal and Instrumental Ensembles.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/Editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Les Meslanges - Thomas van Essen & Volny Hostiou

I was working just near from here, and every day I was watching her and I loved it. And when it burned, it was very painful for me.

Visitor 2 at Notre Dame:We were very unhappy to hear in Greece. We are all crying.

Visitor 3 at Notre Dame:It’s France. It’s Paris. You have to go and see it.

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:It’s iconic. It’s part of history, and it’s really interesting that I’m never probably gonna be able to be in it, and see it how it was originally. It’s the first one I’ve ever seen the building, and really sadly, it’s been destroyed.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Mike Axinn and I have a story about sound. Is sound material, I hear you ask. Well, art critic and philosopher Boris Groys says that although thought of as immaterial and invisible, sound can actually induce a material sense of space.

Sarah Monk:It also has the power to trigger emotions, reverence and can bring to mind memories of other times. So when Mike suggested a story about the restoration of sound in one of the world’s most iconic and historic buildings, we grabbed it. Around 6 PM on 15th April 2019, during mass, a fire alarm sounded at Notre Dame Cathedral. Heads were raised and then lowered again, assuming a false alarm. But to be cautious, an evacuation began.

Sarah Monk:30 minutes later, a second alarm sounded confirming a fire under the eaves of the roof. Meanwhile, art and religious relics were being removed by a human chain of emergency workers and civil servants while worshipers rushed to safety. By 7 PM, Parisians watched in disbelief as the oak beams of the cathedral’s roof, some dating back to 13th century, went up in plumes of smoke. By 8 PM, the cathedral’s spire collapsed in front of horrified Parisians and millions of TV viewers all over the world. By the following morning, it was clear that most of the cathedral’s roof had been destroyed, and a large area was contaminated with toxic dust and lead.

Sarah Monk:In 2023, with the reconstruction well underway, Mike and I went to Paris to find out more about the role that sound is playing in the church’s restoration.

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:Who knows what it’s gonna look like when it’s finished?

Mike Axinn:And could you imagine the sound of it?

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:Not like this.

Mike Axinn:What would make sense for a cathedral for how it should sound?

visitor at Notre Dame:Oh, it’d be angelic, most likely.

Visitor 3 at Notre Dame:Just like the soundtrack on a movie. You’re lost if it’s not right, but you’re consumed by the visuals.

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:You would imagine, like, quite spiritual hemming, quite low sounds, that sort of stuff. Do you have any reference of what it might have sounded like before?

Mike Axinn:Yes. In fact.

Brian F.G. Katz:What got us, I guess, the foot in the door was a project on how to get 3 d audio on radio and television. And as part of that project, we were working with the National Conservatory who was recording a concert at Notre Dame. We did the recording. We did some measurements and created a virtual reality version of Notre Dame, calibrated it, and that actually gave us the pre fire state of Notre Dame so that when the fire happened, we realized that we actually had the only measurements of Notre Dame on record. In the very early days after the fire, I started getting calls of people saying, hey.

Brian F.G. Katz:Do you realize you have the only recordings of Notre Dame? And so then we started making contacts to them saying, we’re here for acoustics.

Mike Axinn:That’s Brian Katz, who codirects the team in charge of acoustics for the Notre Dame restoration. We met Brian and his colleague David Poirier- Quinot on the Boulevard Saint Germain, where they proposed we start with lunch at a local cafe. On a gorgeous summer day, we sat amongst the lunchtime crowd and shared 2 dozen oysters followed by plates of delicately fried fish and chips. Aah.. the rigors of grinding out our podcast.

Brian F.G. Katz:These are the smaller ones. So it’s the dozen of the finclair and then a dozen of the crancas. And then there’s butter, vinegar, and lemon.

Mike Axinn:This is my dream of being out on the boulevards in Paris eating oysters.

Sarah Monk:Thank you for having us here. Could you introduce yourself in your own words?

Brian F.G. Katz:So my name is Brian Katz. I’m research director with the CRNS, currently at the Sorbonne University in the d’Alembert Institute, a researcher in virtual reality, spatial hearing, and room acoustics. I co coordinate the acoustics working group, which is part of the scientific committee put together by the French National Research Foundation and the Minister of Culture. So we are there to provide help and assistance to the reconstruction for any questions or help that they may have.

visitor at Notre Dame:And my name is David Poirier Quinot. I’m a post doc in Brian’s team, and I’ve been since 2012 when I did my PhD with him. And I’m really much interested in AR, VR technologies, and acoustics, and visuals, and everything else. But what needs to happen so that your brain thinks that is a real thing happening in front of me.

Brian F.G. Katz:There’s 3 main kind of focuses of the work that we’re doing. So one is kind of documentation, historic reconstruction to remember the environment. So that’s a lot of what the measurements that we’re doing is, what was Notre Dame like at this time to kind of have records.

Mike Axinn:Brian goes on to explain that the second focus

Brian F.G. Katz:Trying to use those historical reconstructions and interactive virtual reality to explore questions, for example, in music history. And then the third is trying to predict how the acoustics of Notre Dame after the reconstruction will be. And so that’s kind of where it has hard fast applications to now. The general rule, I think, that everybody’s running by for the restoration is it should be the way it was right before. So restored to the way it was in 2018.

Brian F.G. Katz:It was a pretty easy target to build it the same way it was with the same materials in the same way, which kind of opened us up to look at more of the history of Notre Dame as opposed to fighting to preserve the acoustic changes that could happen and has kind of allowed us to say, well, how has the acoustics changed over the centuries? You know, what was before?

Mike Axinn:Mylene Pardoen is the codirector with Brian of the Notre Dame Acoustics Working Group.

Sarah Monk:My name is Mylene Pardoen. I’m a research engineer at the National Center For Scientific Research. I work at the Maison des Sciences de l’homme de Lyon Saint Etienne, and I’m a soundscape archaeologist.

Mike Axinn:In addition to providing us with a visceral sense of how the cathedral’s original construction might have sounded, She also seeks to provide insight about the materials used and the tasks performed by the stone carvers.

Sarah Monk:My specialty is capturing the gestures of craftsmen. It’s like taking photographs and making proposals on historical models for Notre Dame. Every sound is unique. Even if you record it several times, it will always be unique. There’s always a little something that’s changed.

Sarah Monk:So we want to be witnesses to a gesture or to a reconstructed scene. We don’t want to be the creator of this scene or this gesture. We’re not the creators. It’s the craftsmen who make it. We’re just witnesses, but we want to bear witness as objectively as possible.

Pascal Prunet:These companies of stonecutters, they’re closer to how we build in a way than us. They do it. And they saw things of which we thought they were more maybe designed and which were probably not completely designed, but differently built, and the result was not completely geometrical in a way.

Mike Axinn:That’s Pascal Prunet, chief architect of historic monuments and part of the architectural team in charge of restoring Notre Dame, who works under chief architects Philippe Villeneuve and Rémi Fromont overseeing the cathedral’s restoration.

Pascal Prunet:My leitmotif was first, research for Notre Dame, second, Notre Dame for research, to discover how Notre Dame was built in a way. Well, try to discover because we’re not sure of everything. We plan it. We think of how it was. We try to discover how the vaults were done and why they had this geometry to be able to rebuild these big holes in the vault.

Mike Axinn:As the architectural team does its work of simultaneously discovering how it was built and restoring it, the audio team has been doing similar work to learn about how the church should sound when it’s reconstructed using 21st century tools to simulate the acoustics in different parts of the church and in different circumstances. As part of her audio documentation of the physical gestures involved in the church’s reconstruction, Mylène Pardoen was provided with special access to record the work of contemporary artisans who are undertaking the reconstruction of the church now.

Brian F.G. Katz:She has audio recorders that are running constantly in the cathedral recording every sound that anybody makes in there to have records for it. And she’s in recording the sounds of different artisans here and elsewhere to have documentation for that.

Sarah Monk:We only have sound recordings to work with. We’re going to tell a story, so we’re going to look for information to try to understand what activities were like in the past. That’s the first point. The second point is, well, I’m a soundscape archaeologist. I have to find these sounds that are hypothetically still in our present so that I can record them.

Sarah Monk:We’re going to look at the stone. We’re going to look at the gesture with which the stone is cut.

Brian F.G. Katz:So that has a historical relevance. We’re trying to use those historical reconstructions and the interactive virtual reality example to explore questions, for example, in music history. So looking at how Gregorian chants and polyphonic chants emerged, what was the acoustics they emerged in, and are they better suited to certain acoustics than others?

Sarah Monk:Notre Dame is arguably the cradle of polyphony in Western European music’s history, and this is where my personal passion was piqued. My father, Christopher Monk, was, according to his obituary, one of the best loved figures in the world of early music and a notable eccentric in an admittedly crowded field. I love that quote. What a perfect way to be remembered. Dad was part of the movement that restored to our sound world, the Renaissance Cornett, a woodwind instrument that is compared to a choir boy’s voice and well known in Monteverdi’s music.

Sarah Monk:More relevant to our story is his enthusiasm for making and playing the cornett’s cousin, the serpent, a long black snake shaped instrument with 2 s bends and 6 finger holes, which is carved in wood, covered in leather, and was played in Notre Dame many centuries ago. So we were thrilled to meet with eminent musicians, Volny Hostiou and Thomas Van Essen, who specialize in performing compositions that were written for and often performed for the first time in Notre Dame. Volny teaches tuba and serpent at the Rouen Conservatoire and creates projects in collaboration with the Musee de la musique de Paris. Among the early music ensembles he plays in is Les Melanges, which Thomas founded. Thomas is a musicologist, flautist, and singer dedicated to early music.

Sarah Monk:As Notre Dame is obviously not yet available, they kindly arranged to chat with us and play in the Abbey of Rouen, where we were given special access to film and

Mike Axinn:record. So I discovered the serpent a little over 20 years ago, thanks to a musician who was the first to play it, Michel Godard, with whom I learned to play it. And I became interested in serpents because as a tuba player making early music from the 17th and 18th century, the serpent is present everywhere. It’s present in the king’s music in particular. It’s obviously present in the great cathedrals like Notre Dame de Paris.

Mike Axinn:The serpent is said to have been invented by a certain Edme Guillaume in 1597. It was one of France’s foremost instruments for accompanying chant in the liturgy. And so this instrument was used constantly until it disappeared. Only to be rediscovered towards the middle of 20th century by Christopher Monk, who was the first to remake serpents. And through this, musicians had access to instruments to replay and try to understand precisely how this instrument was used.

Mike Axinn:This is a copy of an instrument in the Musee de la Musique in Paris. It was made by a builder named Stephan Berger based in the Swiss Jura region, who did an enormous amount of research, notably on leather since this instrument is made of wood covered in leather. He found a way of tanning the leather to reproduce what he had seen on historical instruments and to cover it with a shellac varnish. So it’s very, very meticulous piece of work. A piece of research that took many years and has resulted in an instrument, I’d say, that’s quite pleasant to play, quite simply to hold in the hand.

Mike Axinn:What was special about making music at Notre Dame before the fire?

Volny Hostiou:Notre Dame de Paris.

Mike Axinn:Notre Dame de Paris is obviously emblematic among French cathedrals. Les Melanges ensemble and I were lucky enough to play there shortly before the fire. And it’s true that it’s an extraordinary place, full of history and music, and a musical tradition that has never been lost. There you have it. For us, it was really a great opportunity to play in this cathedral.

Mike Axinn:Volny and his colleague Thomas performed a credo or liturgy. In addition to similarities in the acoustics of the Rouen Abbey to those of Notre Dame, the piece they performed for us here was written by Jean Francois Lalouette, whose history as a composer and music director included both churches. Thomas explains. Jean Francois Lalouette was a composer born in 1651 and died in 1728. He was music master at Notre Dame de Rouen and music master at Notre Dame de Paris.

Mike Axinn:This is a credo he wrote in plain song. It’s written in big letters as if it were Gregorian chant, but it was written in his own time. The serpent has a particularity of actually playing a lot with the acoustic. It’s an instrument that has very, very little directivity. The serpent, in fact, tends to fill the space.

Mike Axinn:And so there’s a sensation, I’d even say a physical one, of the player actually resonating the space. And, therefore, while playing, you must take into account the acoustics and the reverberation of the space. And so it’s true that a church acoustic here with a rather long reverberation really enhances the sound of the serpent. I’d say that, obviously, we’re dealing with the interpretation of music of which we’re not looking so much for historical truth but for information. And we’re trying to understand and, therefore, rediscover the ways of doing things that may not have lasted to the present day.

Mike Axinn:The serpent had become an extremely common instrument in French churches, and it remained so for a long time until choir organs, in fact, began to gradually replace the serpent in the accompaniment of plain song.

Visitor 2 at Notre Dame:It’s very nice to have an organ in the church. The sound makes you to relax more and, to connect with the God.

Mike Axinn:The organ, in fact, is central to the third focus of the work being done by Brian Katz and his team.

Brian F.G. Katz:So the great organ wasn’t affected by the fire other than being dusty from the lead pollution and things like that, But the actual instrument wasn’t damaged. The choir organ was damaged, irreparable, and also wasn’t historically classified. So you can replace it. The choir organ has been sitting in the historic location, which is in the choir facing the choir, which is great for the choir, but actually projects very poorly to the rest of the public. So the idea was they wanted to add another register, basically a whole another keyboard.

Brian F.G. Katz:They wanna double kind of the number of pipes to get more level and also direct it more towards the general nave and not just to the choir. Where you are and where you’re performing from and where you can be heard is very important. There’s 3 main volumes. You have the choir area, which is semi enclosed from kind of the wood seating and everything. You have the nave where all the general public is, and then you have the transept, kind of this intersection, which acts as this kind of acoustic barrier buffer.

Brian F.G. Katz:The types of things that they sing and the way they interact with the public has evolved over 10, 20, 50, 100 years. And to engage more with the public, they need to be able to hear what you’re singing. So to sing in the choir of Notre Dame inside the choir is great because there’s a lot of wood paneling near you when you get that reinforcement. But no one outside of the choir can really hear you very well because that sound is contained. If you then move to the transept, you are singing in an open field.

Brian F.G. Katz:And the sound just leaves and you’re lucky if anybody hears it. And then if you go into the nave, then you’re where the audience is, the general public, and that’s heard differently. So we were kind of putting all of those configurations into our acoustic model and looking at how the sound would be heard in different regions in the church.

Volny Hostiou:Well, there’s a lot of subjectivity, and you have to just, I guess, with the best conscience, do your best to create realistic conditions for them.

Brian F.G. Katz:Yeah. From the science side, my job is to provide the options so the people who make decisions can make an informed decision.

Volny Hostiou:You guys do have to have some understanding of materials, and of course, you work closely with the architects.

Brian F.G. Katz:Working with the architects more is on the Notre Dame project with this idea of we’re gonna build it as before, a lot of those questions became moot because it was like, it was this kind of stone before. We’re gonna replace it with the same kind of stone. There were proposals floating of, I’m gonna replace the vaulted stone ceiling with a glass ceiling and have put a park on top. Those were the things that were circulating when the project started. And that’s when we were very active and we need to talk to somebody.

Brian F.G. Katz:Macron’s announcement of build it as before came after we were already starting to have discussions with the architects.

Volny Hostiou:Well, the wood is gonna be new necessarily.

Brian F.G. Katz:A lot of the discussion about the roof and the forest, and that’s outside of the acoustic volume. That’s the attic.

Mike Axinn:What Brian refers to as the forest, the part that burned away, is obviously central to the work of Pascal Prunet and the architectural team.

Pascal Prunet:They all say, forest is, the roof is a forest. For me, it’s the cathedral, and it’s the gothic architecture. Gothic architecture is a forest. It’s a kind of stone forest. It’s a petrified forest.

Mike Axinn:Prunet conjectures that it was through the building process that the original builders were able to work out many of the principles.

Pascal Prunet:This carpentry work, as the vault, is an expression of how this cathedral was a laboratory of gothic architecture. At the time Notre Dame was being built, other cathedrals were growing and and there were architectural changes and discoveries. If you read Panofsky, you know, Erwin Panofsky, gothic architecture and scholastic thinking, he speaks about, how the thing grows from a bit like a tree. It’s a very modern thinking. This church has a real evolution.

Pascal Prunet:It begins with a kind of relative light structure walls, which are not very thick, and they get enhanced. And you always feel that in Notre Dame. It’s very fragile, and it has been deformed. The beauty of this cathedral is related to its fragility in a way, to its lightness, to the relatively low thickness of its walls, and it will be transfigured in a way. Because with the lightness of the surfaces, it will be very blond.

Pascal Prunet:It will be a place for light.

Brian F.G. Katz:One of the most moving, touching concerts I’ve ever been at in Notre Dame was a concert by the soloists of the choir. And I think there was maybe 4, at most 6 of them. And we were seated in the choir section, which is normally where no one can be. And as they sang, they moved in and out of the choir to the transept and played with that volume.

Brian F.G. Katz:Basically, in taking a few steps forward or backwards, it became someone was singing next to you in intimacy too. They were exciting the whole volume and were remote and ephemeral. But they were clearly aware of it and played with it.

Mike Axinn:For a player like Volny Hostiou, this energy and the ability to actually be playing the space itself has great resonance, so to speak. When you’re an instrumentalist or singer who’s often asked to play in historic places, it’s really about rediscovering the atmosphere of a place and then trying to have a dialogue with it. When you play in a place, I think you’re influenced by all the parameters. Yes. The atmosphere that emanates from it, the harmony of proportions, the space, the light.

Mike Axinn:In any case, I have the impression that when I play the serpent in a space like this, I’m actually taming it, becoming one with the space. I think that’s what interests me most about the instrument too. (You play the space). That’s it exactly. And it’s true that in particular spaces, you almost get the impression in the resonance of the space that you’re not just playing your instrument, but that you’re playing the entire acoustic of the space.

Mike Axinn:The question is, of course, once Notre Dame is reopened, whether we’ll have the impression of rediscovering the acoustics we once knew there, or whether they’ll be a little different. We’ll have to find out.

visitor at Notre Dame:What really matters for singers and musicians is the amount of energy you get when you play a note. You get the energy, and it’s like, okay. I can play in that space as opposed to I can’t because it’s all mud. That’s one of the things I miss when you sing in a play. So the reason you sing in your bathroom is because you are supported by all that early energy.

Mike Axinn:David Poirier-Quinot brought expertise in virtual reality, augmented reality, and AI techniques, which not only helps the team envision how the church will sound before it’s actually been reconstructed, but offers tremendous possibilities for how the church will be experienced in the future.

visitor at Notre Dame:We are interested in perception and how to recreate it, but then to tweak it so that the reflection on the floor of Notre Dame is just right or the audio actually sounds correct now.

Brian F.G. Katz:I mean, I think what’s kind of the game changer in the field is that we can now create things that sound plausibly real, and we can process things fast enough that you can interact in real time with things. So, I mean, this idea where I can have some singers that have sung in Notre Dame. They can come into the lab, sing in our system, They sing in our virtual version, and they go, yeah. I recognize that. Right?

Brian F.G. Katz:That sounds, like, familiar. Yeah. Puts us in a very different state than we were, you know, 5, 10 years ago.

Sarah Monk:What’s gonna be the next big technological change?

visitor at Notre Dame:You’re so not ready. I’m so not ready. Basically, AI is a massive shortcut to make the acoustic right or that kind of thing. With AI, you can go, well, that looks like a church. What’s the acoustic of that church?

visitor at Notre Dame:It solves problem very quickly if you know how to handle it. But that’s not the point. For me, the next really interesting thing audio wise, sure, but mostly AR wise will be that whole augmented reality slash spatial audio they’ve been talking about. The 4 of us, for example, it’s nice, but we have, like, what, 3 weeks process of rendezvous and then Paris and all that. It’s painful.

visitor at Notre Dame:It’s not bad, but it’s just compared to just, like, crank a wheel or whatever, plug a pair of glasses and just be together, same environment, acoustically, exactly the same, all that synthesized vinyl, exactly transparent the way I like it. Because otherwise, it’s a Skype, and you don’t wanna do a Skype. And the main reason it’s not natural. Eye contact is not here. And, basically, you feel, like, feel it’s a real human being because it’s 3 d and because you hear the person as you should and because, basically, they are standing 3 meters from you.

visitor at Notre Dame:Everything is bright enough so that your brain tells you there is a human here. And if you move your hand, you’ll touch them. And I feel that’s kind of, like, what’s coming and what’s really exciting is that.

Volny Hostiou:What about the oysters?

Mike Axinn:Sadly, there’s not yet technology to allow us to recreate the actual experience of eating oysters on the Boulevard Saint Germain.

visitor at Notre Dame:Yeah. True. I mean, you could order from the same restaurant, and then get shipped to your place, but then no.

Volny Hostiou:Don’t you think you’ll be in there one day?

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:Maybe, but not originally how it was before this happened.

Visitor 4 at Notre Dame:Quite spiritual, quite vast. I could imagine there’s a real essence of imagining how small you are in such a building like that.

Visitor at Notre Dame:I’m not religious, but even if you don’t believe in God or something like this, you can just see how beautiful everything is.

Brian F.G. Katz:That sense when you walk into the church and you already lowered your voice level and you try to make less noise already puts you into that sense of a certain acoustic. And the fact that you hear the murmuring of everybody else doing the same thing.

Mike Axinn:The absence of items like furniture has enormous impact on the acoustics, and so also does the existence of tourists.

Brian F.G. Katz:The noise of tourists is something that has been evoked by numerous people within the cathedral and outside of how to reduce unwanted noise in Notre Dame. And it will only get worse with the reopening and its popularity. So we can use our acoustic simulations to try and look at remedies. Maybe we can, you know, add carpeting or different absorbing material or other things to really focus on reducing that noise without diminishing the general acoustics of the cathedral.

Mike Axinn:You have more scope for optimization, I would think, than the architects do.

Brian F.G. Katz:I mean, in terms of the reconstruction, we are a scientific advisory committee, so we can provide advice. We don’t get to decide anything, but we try to respond to issues that are raised and what we think would be the solutions.

Mike Axinn:They’re making materials decisions based on your advice.

Brian F.G. Katz:Not yet, but we hope so. I mean, I think it was in the nineties they installed a runner carpet in the

Brian F.G. Katz:circulation area to kind of diminish the noise of tourists.

Brian F.G. Katz:But I don’t think there was an acoustic study. They just said people’s shoes are making noise. Let’s put a carpet in. So I think what we’re hoping now is to have a better idea of the kinds of noise that is disturbing, and maybe we can actually have a more intelligent solution to kind of remedy that. And and there’s an evolution.

Brian F.G. Katz:The fact that the new choir organ should have a bigger range musically than the previous one is because there is an evolution in the music that is being played. This is a living, evolving building, and we know what’s going to happen. So it’s trying to keep it in the same spirit but always improving

Mike Axinn:So we’ve gone from the noise of Parisian streets to the perfect audio environment.

Brian F.G. Katz:I don’t know about perfect, but it’s pretty good.

Mike Axinn:You gotta look when I said perfect.

Brian F.G. Katz:So here we are at our virtual reality

visitor at Notre Dame:A facility. Facility. A facility. Yeah. It’s a room.

Brian F.G. Katz:Our virtual reality experimental facility. It’s all optics.

Mike Axinn:I mean, actually, we’re in the tiny box, but

Brian F.G. Katz:we’re in a highly intricately designed tiny box. The conceptual idea of the room is it’s multifunction used by many researchers, so there shouldn’t be anything on the floor. So even though it’s small, since everything is stuck on the walls, you get a bit more space than you normally would. Nice. So we have 32 speakers Mhmm.

Brian F.G. Katz:Kind of arranged in a squashed sphere. Mhmm. We have a subwoofer, but we also have a system that can handle various headphone reproductions. We have infrared tracking, so you can actually do motion capture of musicians or people interacting in virtual reality. We can have VR headsets.

Brian F.G. Katz:We can also do immersive projection on half the room and have you in another virtual environment.

Mike Axinn:So how are you able to use your facility, this place, the technology, and so forth to help understand these determinations?

Brian F.G. Katz:In the computer simulations, we can listen to the impact or look at the change in measures like reverberation time. The facility that we have here, which is really designed for an interaction, is really helping us mostly study with musicians, and we can put them in different historical versions of Notre Dame and get their either reactions or see how their musical production changes as a function of the acoustic conditions that we put them in. So we had measurements from 2015 in the same lab that I’m in. Predecessors in the mid eighties had also done measurements. So we have this kind of historical series of measurements.

Brian F.G. Katz:And the idea was now we have the post fire. I want a data point to say this is what the acoustics is at this point. Knowing full well that that wasn’t the acoustics, you know, after it reopens, but just to have kind of a an evolution of the acoustics and to be able to then remodify our acoustic model to take in that into account.

Mike Axinn:How do the different materials affect the audio just in general sense?

Brian F.G. Katz:Well, hard things reflect sound. Soft things suck it up. Notre Dame, it’s mostly stone and stained glass windows. Right?

Brian F.G. Katz:So there’s very little absorbing material. So that’s how you end up with reverberation time, which is kind of a measure of how long it takes the sound to decay. You get reverberation times that are very long. So note to them is something on the order of, like, 8 seconds. There’s a bit of absorbent material.

Brian F.G. Katz:There’s a bit of carpeting here and there. There’s a bit of chairs, but it’s basically just a big hard volume. So material wise, if we’re looking at the restoration, any changes to those materials of what they were before could have an impact of what could happen in the future. And the reference data that we have for that, for example, is the measurements of our lab that were in the late eighties, and then the measurements that we did in 2015 show a measurable difference in reverberation time. And we were kind of confused about that and wondering where that was coming from.

Brian F.G. Katz:And then we noticed that this carpet that was added to actually reduce the foot noise of tourists actually reduced the acoustics of Notre Dame. And when we interviewed people in the choir and the organist, they actually also commented on the fact that in the early nineties, the reverberation time fell. And so you can see kind of the direct link. And I guess one of the big keys on absorption in reverberation in spaces like this is the first bit of soft material you add has the most effect. So if I have a totally stone building and I put in a 100 square meters of carpeting, you get a significant effect.

Brian F.G. Katz:If I add another 100 square meters, you have kind of a diminishing returns quite rapidly. So that addition of a small change when there’s nothing kind of impact the the acoustics significantly, And we’re kind of looking at that in the future of maybe we can propose something better for reducing tourist noise that is maybe not just footfall noise, but also reduces the noise of cell phone clicking and things like that to better help the cathedral in what they’re looking for in terms of the future acoustics.

Mike Axinn:What are they looking for?

Brian F.G. Katz:In talking to, say, the choir and the clergy, tourists have their purpose, but they shouldn’t distract from the religious aspect and the holy aspect of the space. So that kind of perturbation, high traffic visitors, and, you know, tour guides that are coming through, and just the whole demeanor of people that has changed over decades of, before you would come into the cathedral and you’d be quiet and you go outside, and then the tour guide would tell you things. Now they’re just walking around hollering during services. So they’re looking at ways to kind of diminish that. In our historical study, if we look at very early Notre Dame when it first opened, there were no side cathedrals.

Brian F.G. Katz:It was just a straight walled box, but there were side chapels and different kind of artisan groups and different families would have little altars in different places and they would all have basically mini services going on constantly in parallel to the main service. And we have records from the 1200s of the clergy complaining about the noise from all these other events going on. And then you see kind of the expansion of the cathedral by the going into the flying buttresses and expanding and making little chapels in each of those and how that actually reduced the acoustic impact of all those little chapels because now put them almost in subvolumes. And we’ve done an acoustic study looking at how that actually improved the acoustics for the main service by having these small cathedrals. So the disruption of the main service by other things going on is nothing at all new in the history of Notre Dame

Brian F.G. Katz:And we’re just now looking, I think, for new ways to mitigate it.

Mike Axinn:What have been some of the most difficult areas slash challenges of your work?

Brian F.G. Katz:That is a very broad reaching question.

Mike Axinn:It is.

Brian F.G. Katz:Yeah. We’ve done historic studies on buildings from the 1900s and from the 1800s. And now we’re looking at a building from the 1100s. Just finding documentation of, hey, what was that made of? And, you know, when was this added, and what was the material here?

Brian F.G. Katz:Already for something from the early 1900s, it was hard, and this just adds a whole level of kind of archival research beyond complicated, and a lot more supposition and kind of looking for some small thread of evidence to justify some decisions. I think that’s your serpent player.

Mike Axinn:We’d invited them to play in the simulator, which would give us an opportunity to compare music made here with what they’d recorded in their Rouen Abbey. You get a much more reverberant impression of the place, a priori, in Notre Dame. Well, it depends where you are. I placed you in the transept in one of the wings. That’s what I really wanted.

Mike Axinn:It’s important because singing in Notre Dame, or at least that, is what I really wanted.

Mike Axinn:Now here’s the fun part. We’re going to play the same clip from Volney and Thomas performing in the simulator and in the Rouen Abbey, And you get to guess which is which. It’s not Notre Dame, but it’s the best we can do in a pitch. Here’s the first.

Mike Axinn:Now the other.

Mike Axinn:Can you guess?

Visitor at Notre Dame:This one is Rouen

Mike Axinn:And this is the simulator.

Sarah Monk:We decided to give the last word to David Poirier Quinot, whose passion for the potential of AR and VR technologies inspires us.

visitor at Notre Dame:I wanna do something that’s not been done before and that is cool. And that’s why I’m really interested today in the AR, VR, audio, acoustic. And basically, today when I close my eyes, recreate a space and can’t feel the difference between a virtual and a real clarinet, but maybe tomorrow talk with someone and can’t say who is the real one. Your computer being aware of your surroundings and making them more like what you want. I don’t know, walking in Paris, for example, but not seeing 50,000 people around you, but 25,000.

visitor at Notre Dame:It’ll be cool. Right? Living in the Paris of 20 years ago where your parents went.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to Brian, David, Mylène, Pascal, Volny, and Thomas. You can find links to them all on our website, materialyspeaking.com. Beginning mid April, The Past Has Ears project is launching Notre Dame Whispers, an immersive audio guide that transports listeners through time and space to the heart of Paris’ most treasured landmark. Free on Google Play, Android, and iOS, it can be listened to anywhere, but it is best with GPS on-site at Notre Dame. As always, you can find photos of the work discussed today on our web site, materially speaking dot com, and on Instagram at materially speaking podcast.

Sarah Monk:Notre Dame is scheduled to reopen December 2024, so keep your eyes open for more on this story, in particular our video of the serpent playing in Rouen, which will be released on YouTube later this year. Thanks for listening, and if you’re enjoying materially speaking, please subscribe to our newsletter on our website so we can let you know when the next episode goes live