Nilda Comas and a maquette of the statue of Mary Bethune. Photo: Gail Skoff

Nilda Comas knew she'd be an artist from a very young age, and now she'll be the first Hispanic master sculptor to create a statue for the US National Statuary Hall. She describes her journey, from a childhood in Puerto Rico to coming to Italy and learning carving skills from the artisans in Pietrasanta.

Following the shocking Charleston church shooting in 2015, the State of Florida decided to change one of the two sculptures representing them in the National Statuary Hall in Washington. They chose to honour Dr Mary McLeod Bethune, educator, philanthropist and civil rights activist. Then, from 1600 entries, Nilda Comas won the commission to create the statue in marble.

Nilda in Giancarlo Buratti’s clay studios in Pietrasanta. Photo: Nilda Comas

Photo: Gail Skoff

Nilda explains how creating a statue of Dr Mary McLeod Bethune was such an extraordinary commission for her. Bethune was born the 15th of 17 children in 1875, in Mayesville, South Carolina to former slaves. As a young child she became eager to learn how to read and write, and soon education – for herself, her siblings and other African Americans – became her key ambition.

Dr Mary McLeod Bethune, photographer unknown

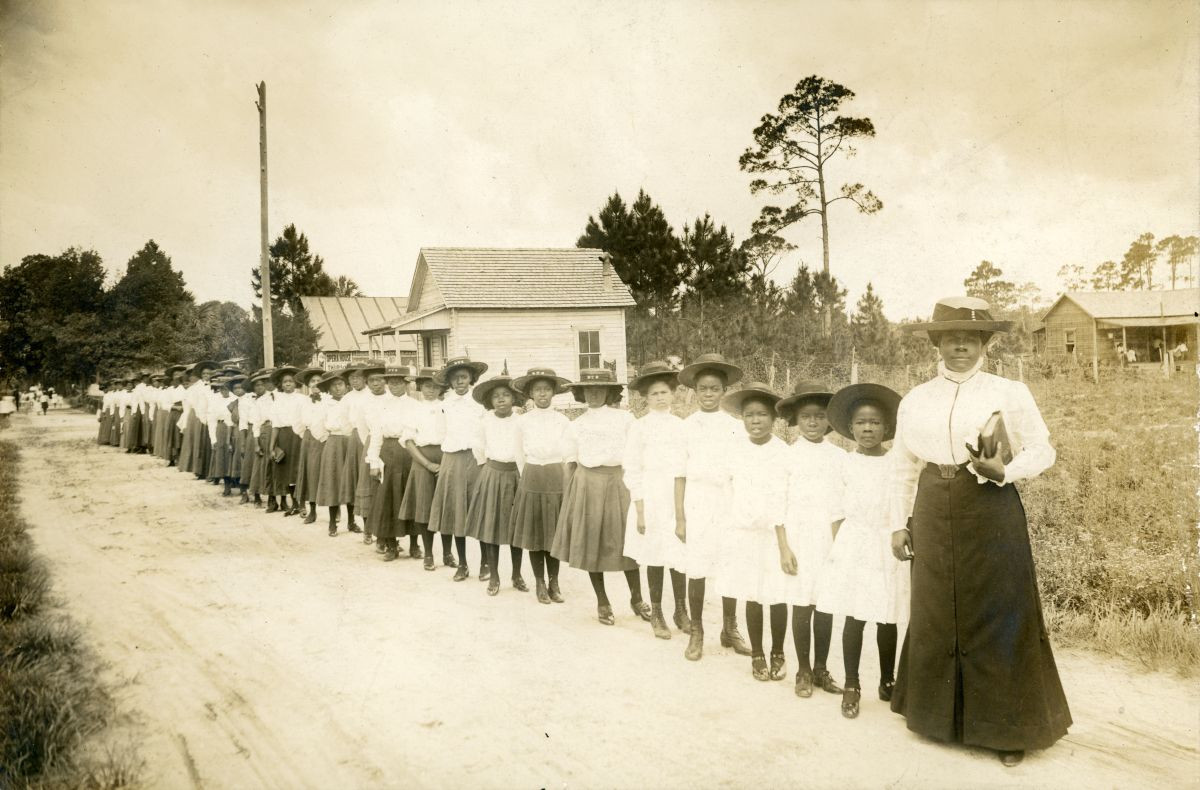

Mary McLeod Bethune founded a school for African American students in Daytona Beach, Florida, which later became Bethune-Cookman University.

Mary McLeod Bethune with a line of girls from the school, circa 1911. Photo: State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

In 1911, Bethune opened the first black hospital in Daytona, Florida. She became a friend to Eleanor Roosevelt and subsequently an adviser to president Franklin D Roosevelt in what was unofficially known as his Black Cabinet. Bethune was the only woman of colour at the founding conference of the United Nations in 1945.

This episode follows the creation of this special commission from Florida’s decision to change their statue, Nilda winning the commission, finding the stone, the process of creating the sculpture, through to the moment it was unveiled in Italy in July 2021. All against the challenges of the last three years.

Nilda at Cervietti’s studios with the piece of statuario marble from Michelangelo’s cave

The statue of Mary Bethune during its visit to Florida, photo: Nigel Cook

After the statue was unveiled in Pietrasanta in July 2021 it was shipped to Florida and went on view in Daytona Beach, before taking a short tour to Bethune's birthplace in Mayesville, South Carolina. Finally it will make its way to the US Capitol for inauguration in the summer of 2022.

We hear from some of the 54 visitors who came to Pietrasanta from the USA for this special event and hear what the African American statue means to them.

Alumni of Bethune-Cookman college before the celebratory concert at Cervietti’s studios, Pietrasanta, July 2021

The Dr Mary McLeod Bethune Statue was unveiled and dedicated in the National Statuary Hall in Washington on July 13, 2022.

Contributors

Thanks to all the contributors to this episode:

Nilda Comas, master sculptor

Nancy Lohman, chair of the Dr Mary McLeod Bethune Statuary Fund

Derrick Henry, mayor of Daytona Beach

Dr Hiram Powell, interim president of Bethune-Cookman University

Rev Thom Shafer of Fort Myers

Kathy Castor, Florida Democratic US representative

Shonterika Hall, Bethune-Cookman alumni

Khalil Bradley, Bethune-Cookman alumni

Hannah Randolph, Bethune-Cookman alumni

Sarah Slaughter, Bethune-Cookman alumni

Jacari W Harris, former B-CU student government president and social justice activist

Yolanda Cash Jackson, lawyer and lobbyist.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound edit/design: Guy Dowsett

Sound recordist: Andrea Gobbi @magazzenosoundproject and @andreagobbi_music

Narrative consultant: Mike Axinn at One to One Box

Music: all courtesy of Audio Network

The Mist On The River, 3424/3 James Taylor

Stuff Of Life, 2017/9 Philip Sheppard

Welcome To Utopia, 3110/2 Philip Sheppard

Mayor Derrick Henry (00:10):

The statue itself is a unifying dimension.

Yolanda Cash Jackson (00:14):

To have her included means inclusion.

Alumni of BCC (00:17):

To see her being honored in this way, it’s amazing. And I do feel as if the whole world should know. Yes.

Alumni of BCC (00:27):

She has captured her soul and her spirit.

Alumni of BCC (00:32):

I’m proud. I’m excited. I can’t wait to see it in Washington, DC.

Mayor Derrick Henry (00:38):

The statue and the whole process is bringing a full light to the grandeur of her life.

Sarah Monk (01:04):

Hi, this is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today’s story starts in Pietrasanta in Northern Italy, where generations of artists have been carving marble since Michelangelo first came here 500 years ago to choose marble for his Pieta. Sculptor Nilda Comas tells us of her personal journey and of a special commission she recently completed, which speaks of the times we live in, the role that statues play, and some of the challenges of the last few years. It also tells of tender cooperation between old allies, both for Nilda on a personal level with the clay, bronze, and marble studios, which she has worked in for more than 27 years, and also historically between America and Italy on the world stage.

Sarah Monk (01:52):

In 2016, Puerto Rican born Nilda won the commission to create the first state sponsored African American statue to enter the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington.

Senator Kathy Castor (02:05):

I’m Congresswoman Kathy Castor of Florida; I represent the Tampa Bay area in the United States Congress. I was first elected in 2006, and it was at that time, after I was sworn in, I learned that every state in America has two statues that represent the state in the United States Capitol in what they call the Statuary Hall Collection. I found out early on that Florida is represented, first, by John Gorrie, he’s the inventor of air conditioning, so that’s quite appropriate for the state of Florida, right? But the second statue is a very obscure Confederate general who was on the side of slavery in the Confederacy in the Civil War era. He was born in Florida, but never really lived there.

Senator Kathy Castor (02:56):

He is not a good representation of our beautiful, diverse state, but it took many years to get people’s attention on the need to replace the statue. It was after the horrendous massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, in the Mother Emanuel Church, where a white supremacist shot people who were worshiping together and who had invited the shooter in, that after that massacre, states and communities started to reexamine their symbols and their statues. And we asked again, the state of Florida, "Please, it’s time to replace our statue."

Sarah Monk (03:36):

First, I met with Nilda in the summer of 2019 at my home above Pietrasanta. Nilda picks up the story.

Nilda Comas (03:43):

The state of Florida decided to change the sculpture that was at the National Statuary Hall. The governor appointed a committee to choose the sculptor. There were 1600 entries; it was a nationwide competition throughout the United States. And from that, they reduced it several times. I was here in Italy when I got that there were 60 chosen now, and so I thought, "Oh," I was getting a little more serious about it. And then from that, there were 10 finalists, nine were men from all over the United States, and I was the only woman.

Nilda Comas (04:24):

We went to Tallahassee, to the capitol, and we made our presentations. And of the group, I was also the only one who could work in marble or bronze. And then I didn’t know who I was going to sculpt because they had not chosen. This was three years ago. And then the legislature of Florida chose, and just one vote she didn’t get, otherwise, it was unanimous to have Mary Bethune.

Sarah Monk (04:55):

So I’d never heard of Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune. I knew she was born in 1875 and died in 1955, but I was keen to hear who she was, and why her statue going to Washington would be significant.

Mayor Derrick Henry (05:09):

I have always known her to be an iconic figure in my community. For me, she served as a model of possibility. Even as a young child, she set an example of the way forward.

Dr Hiram Powell (05:23):

Well, Dr. Bethune is best known by most people for her political activism in the United States. She was sort of the precursor to Dr. Martin Luther King in terms of advocating equal rights for all.

Mayor Derrick Henry (05:38):

A little girl born on the heels of slavery starts her own college, integrates baseball essentially, to serving as the advisor to four presidents, an extraordinary life.

Nancy Lohman (05:56):

When you think about what was going on in the United States, the obstacles she must have faced, the doors that must have been closed to her, the people that didn’t receive her, but she calmly but firmly persevered.

Jacari William Harris (06:12):

And that’s just what Mary McLeod Bethune did. She rose above the obstacles, the circumstances, the issues, problematic people, and she founded one of the, the best institution there is in the country.

Dr Hiram Powell (06:26):

She makes the statement: Faith is what makes all things possible. I think it was her faith that allowed her to believe, because not only was she doing things that Blacks could not do, she was doing things that women as a whole could not do at the time, and doing them boldly, and nobody was stopping her.

Yolanda Cash Jackson (06:50):

This Black woman who had $1.50 and sold potato pies to provide educational opportunities, who was counsel to not just one president, but several presidents…

Nancy Lohman (07:05):

She represents a person who fought for the education of African Americans, but fought for education in general in the sense that she really believed education was a key to the future.

Mayor Derrick Henry (07:19):

She moved to Daytona Beach where she decided she would start a school there, and the Ku Klux Klan said, "Not here," but she said, "Yes, I will build it." They said, "No, you will not build it here. We will burn it down." She said, "If you burn it down, I will build it again."

Nilda Comas (07:39):

And she achieved things that were actually more important than anyone else, I believe. Because, okay, Martin Luther King was pacifist and he was an amazing orator and he guided towards what actually Dr. Bethune achieved in law, because it’s really what’s written and what’s the law is what at the end counts.

Nilda Comas (08:05):

They call her the "mother of civil rights", and the way that she achieved this was such a very intelligent way. Because at that time, she had to be so diplomatic about her ideas, about what needed to be done, what had not been done, what was an embarrassment, and what needed so badly to become law. She rented Abraham Lincoln’s office when she moved to Washington, DC. So all of a sudden people are talking about, "Who is this person?" She’s a African American woman and she’s right across the National Gallery, and she’s having these teas and inviting every head of the movements for the African Americans, like the veterans movement, education, all of the heads of those movements were invited to tea on Fridays. And she there, very diplomatic would ask, "Would you please write down what you are trying to accomplish for your group?" And with that, she would take those to Franklin Roosevelt. She would actually hand it to him.

Nilda Comas (09:28):

I asked when I went to the Library of Congress, "How many times a month do you think that Dr. Bethune would go to the White House?" And remember the times, the only African Americans at the White House were the help. "Nine times average," they say, that she would go to the White House in a month.

Sarah Monk (09:52):

It’s unbelievable.

Nilda Comas (09:53):

Yes. She found a way to get things done and become law, and also help in a way that no one else had helped because they didn’t have the representation in the Senate or in the House of Representatives.

Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune (10:12):

In these times, Mrs. Roosevelt, we feel that in order to achieve the goal of civil and human rights for all, it is necessary for women of all races and creeds to know and understand each other. The National Council of Negro Women serves now as a clearinghouse for the women of our major organizations, but this is not enough. We need the strength of all women who believe as we believe; and they need us, for none of us can do much alone.

Nilda Comas (11:17):

She wanted to start this university. And she started it in a dump ground that she paid $1 for this land. So she had this dream about this school, and she went over to Rockefeller, who had been buying land all around there, she made an appointment to go see him. She talked to him all about the university and he said, "I should take some time and go and see the school." And she said, "Well, the school is only in my mind, but if you help me with some money, I will make it a reality."

Sarah Monk (11:52):

Wow.

Nilda Comas (11:52):

"It was just a dream," she said.

Sarah Monk (11:54):

Nilda will be the first Hispanic master sculptor to create a statue for the US Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, and I asked her to tell me how she became an artist.

Nilda Comas (12:07):

I was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and I used to go to the museum when I was like 7, 8, 9, and copy paintings. My grandparents gave me a French easel, and I used to walk from their house, which was at the end of the street, to the museum and sit there and paint. And I guess I was nine when some lady offered me $500 for a painting that I did, a copy of one of the red cardinal dressed Velazquez. And so I copied that painting many times because I love the painting and I’m very fond of Velazquez. I didn’t know that that was the way to do it, I was just a little kid, but I just said, "No, I’m not happy with this one. I do another one." And I would just do it until I was like… I was sitting painting when this lady comes and she said, "Is it finished? It looks finished." And I said, "Yeah, I guess it is finished." And then she said, "Would you sell it to me for $500?" And I said, "Well, yes."

Nilda Comas (13:09):

I never worried about being an artist, I just said, "Yeah, I’m going to do that." I was always doing things. I made puppets and we had these puppet shows with my brothers and friends. Our neighbors look forward to our puppet shows and they would pay to come to our puppet shows and buy popcorn and everything.

Sarah Monk (13:29):

Did you make up the stories too?

Nilda Comas (13:31):

We made up stories. We had a whole group doing different things.

Sarah Monk (13:34):

Fabulous then. It sounds so fun.

Nilda Comas (13:39):

Yeah. So it was, growing up, very easy in Puerto Rico at the time, it was very nice times. And my father had all these friends who were artists because he used to teach at the university, and then he stopped because he wanted to make more money and they didn’t pay very much. And so he was kind of a frustrated artist in a way, because he had a business and his friends were all artists. But he never disconnected from that, so we would go to their shows and openings and we would play in their studios. I used to pose for one of them. And so it was really fun growing up, but it was natural to be an artist, I think, in my mind.

Sarah Monk (14:23):

And from there, did you self-teach or did you go to art college?

Nilda Comas (14:27):

First, I went to University of Puerto Rico my first year, and they didn’t have a good art program, so I was in the humanities and philosophy taking some classes, and then I went to Texas. There was a teacher that I like and I thought I was a painter, but anyway, ended up being more of a sculptor than a painter, even though I do, I just finished two life size portraits, when you asked me if I was doing any oils.

Sarah Monk (14:53):

Were they commissions?

Nilda Comas (14:54):

Yes, they were commissions. And so I studied in Houston, I got my BFA there, and then moved back to Fort Lauderdale where I had been going as a college student and my grandparents own a home there, so as a child I used to visit. My grandfather was in the rum business, he was the president of Don Quixote Rum, and the sugar business.

Sarah Monk (15:20):

Oh, wow.

Nilda Comas (15:20):

So we used to go to Florida because they had a lot of land there for the company. And that’s how I ended up staying in Florida, because I got married and my husband was from Texas. Then I had a real estate office with my husband for 17 years. I always had my studio, but I always been an artist. I always thought of myself as an artist, and this was just some way to make more money, but my other thing was always having my studio at home and working and doing different works and exhibitions and so on.

Sarah Monk (15:56):

It’s so refreshing to hear you say that because I think a lot of people feel you have to be one thing or another.

Nilda Comas (16:01):

Right.

Sarah Monk (16:02):

And actually, realistically, it doesn’t always work that way, and I think people get put off doing artistic things when it doesn’t immediately pay.

Nilda Comas (16:11):

I think anything that you get up every day and you do all day, you get good at it. Doesn’t matter what it is, you’ll eventually find your way with that. And so I had a visit from a sculptor named Bruno Lucchesi. He looked at my work and he said, "You shouldn’t be doing real estate, you should just do this," and so that kind of got in my mind.

Nilda Comas (16:36):

This was like in April, and he called me in May, and he said, "What are you doing this summer?" And I was so proud of myself, I said, "Well, I just booked a flight to go to Arizona and to New Mexico, and I’m going to see some shows and some workshops that are there, some sculptors." And he said, "Why? You should go to Italy. Why don’t you just cancel that, just go to Pisa, fly to Pisa, and take the train and go to Pietrasanta, and I’ll write some letters for you?" And I said, "Why not?" So I did, I canceled the other and I came to Pietrasanta with Bruno Lucchesi’s letters. One was to the Cervietti Studio.

Sarah Monk (17:16):

And how long ago was this?

Nilda Comas (17:18):

26 years ago.

Sarah Monk (17:19):

Well, how was your first impression? How did you feel when you got here?

Nilda Comas (17:22):

Oh, I remember, I was so excited. Leo Muti was working at the Cervietti Studio and he happened to be around when I came in, and he saw me with this big suitcase and he said, "Do you need help?"

Nilda Comas (17:34):

"Yeah," I told him. I said, "I have these letters from Bruno Lucchesi, and one is to the Cervietti Studio."

Nilda Comas (17:39):

"I work there," he says.

Nilda Comas (17:41):

"Then, the other one is to Marcello."

Nilda Comas (17:43):

Oh, I know Marcello. Oh, yeah."

"And then the other is to the…"

Nilda Comas (17:46):

"Oh yes, I’ll help you," going over to Ivano’s, which was Albergo Italia, right there by the Palagi. And then I saw the whole street and I could hear ting, ting, ting, ting, and ta, ta. The whole street were studios then. And he walked me and introduced me to everybody around from one studio to the next, to the next, to the next. And I couldn’t believe, I thought I died and gone to heaven.

Nilda Comas (18:09):

But my letter was to go to Marcello Tommasi, and that was clay studio. He really knew a lot, so I was really lucky to have been there first. And I used to go and ride my bicycle, but on the way there were some studios. And the windows were up high, so I used to stand on my bicycle and watch Enzo Pasquini. Days and days I was like that, and I started coming earlier and earlier and watching him and I said, "My God, he is just so good," And then I would go on to Marcello.

Nilda Comas (18:43):

Then one day, he comes out. I was scared because he knows that I’m watching, I thought he never knew. But then he said he could smell my perfume. He knew that I was getting… Oh my God, I didn’t know it was so strong, but anyway. So he said, "Yeah, come on in to the studio. Would you like to draw the sculptures, the plasters?" I said, "Yeah, why not?" So I came even earlier and he said, "I’ve watched you, you come in earlier and earlier. I’m here 6:30 in the morning." I had to be at Marcello’s like at 9:00; that’s a lot of time.

Nilda Comas (19:16):

Then I started drawing the plasters and he said, "If you can draw like that, I can teach you. I can teach you to carve marble." So I went over to Marcello and I said, "Listen, I really want to learn how to carve marble, and he’s given me an opportunity." And he said, "Who is it?"

Nilda Comas (19:30):

"Enzo Pasquini."

Nilda Comas (19:31):

"Oh, Enzo! Oh!" So I went to Enzo.

Nilda Comas (19:36):

I finally met Franco, which I already knew from going up in the mountains, because we had what we call the sculptoristas on Sundays and go up climbing in the mountains. And so I only knew most of them just by their first name, so I knew Franco as Franco, but there are so many Francos. But I should go to where Bruno told me, he told me to go to the Cervietti Studio. I go over there and I see Franco standing there, Cervietti, Franco Cervietti. And I didn’t know, I just knew he was Franco. And so I gave him the letter, I said, "I’m supposed to give this letter to Franco Cervietti. And he looks at me, because he didn’t realize I didn’t know he was Franco Cervietti, and he said, "I am Franco Cervietti, I’m the big boss here." And I started laughing because I waited and waited because I was afraid to come and bring this letter to Franco Cervietti because I didn’t think I knew enough yet. And then he said, "Of course you can come to my studio and work." And I used to see people on the fence wanting to come in, from all over the world, and so I said, "How lucky I am."

Sarah Monk (20:46):

A day or so after I first interviewed Nilda, I drew up in front of the famous Cervietti Studios on the edge of Pietrasanta. A small, white Fiat 500 is dwarfed by a towering marble statue of a man in Ecclesiastical robes brandishing a book. Around him are large cubes of marble, and behind him, a building with a pink facade. Nilda told me how much she had learned from the artisans at Cervietti’s, how she served a kind of apprenticeship moving from one to the other, learning their specialties. One artisan only carved drapery; another, hands; a third, just faces. Over time, some have died, but the skills often pass on to the next generation and the studio still has a family feel.

Sarah Monk (21:36):

Tall front doors open into a hangar-like building. There is noise and there is movement as a truck carts marble around. And in the distance, I see an artisan wearing overalls and a boat shaped newspaper hat, bending over a chunk of marbles suspended on a sling. Nilda and I browse the photo gallery of past visitors on the walls and meet Franco Cervietti and his staff.

Nilda Comas (22:00):

Ciao.

Sarah Monk (22:01):

Ciao.

Nilda Comas (22:05):

He owns the original plaster cast, the only one ever done directly from the David when they decided to make the David, a second one, to put in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the copy.

Nilda Comas (22:27):

Franco Cervietti (22:29):

Ciao!

Nilda Comas (22:31):

And over there, they cut the marble. See?

Staff at Cervietti (22:34):

Nilda Comas (22:36):

That was my dream, to do a big piece in Statuario marble, and it’s almost impossible.

Nilda Comas (22:48):

Everybody said to me, "You’re not doing her in bronze, in a dark patina?" I said, "No." Through history, I think that one of the highest honors that you can give a person is to do a marble sculpture. All of us sculptors wish to find Statuario, which is the finest of all marbles, soft, easy to carve, but it is so compact that we can get a lot of detail, so it is the best all through history.

Nilda Comas (23:21):

However, a big block like that is very hard to find. Franco knows how much I wanted to get the best marble for this work, and he’s been to the National Statuary Hall, and he said, "We have to get a really good marble for this work, okay?" I used to go up in the mountains and see the different caves, and so I went with him in July. There wasn’t any available. But then three weeks later he called me and he said, "They have gone to an area," from the cave where we visited, Michelangelo’s Cave in Carrara, "They think they can get a big block."

Nilda Comas (24:01):

Maybe it’s been over 30 years since they gotten a block that large from that cave. I was just so surprised that from that cave, where all of it was just all broken up, there would be a piece that large. He said, "Bring it down, bring it down," because he knew what would happen, a bidding war. But he called me and I called the president of the university and I said, "We have found a piece of marble. We will never be able to find another one like this. I am going to go ahead and purchase it." And so he said, "We willwire the money right away," and they did. The last time I was here, someone came by the studio and offered me five times what I paid for it.

Nilda Comas (24:57):

And here is Mary Bethune, see?

Sarah Monk (25:00):

Oh!

Nilda Comas (25:00):

There she is in the plaster, waiting for the marble, to get her marble.

Sarah Monk (25:06):

Beautiful!

Nilda Comas (25:06):

And so she’ll have the rose. Of course, there’s a lot more finishing work to be done, but this is the model. And from there, we take off, and so the rose will be in black, all in black.

Sarah Monk (25:19):

I see that Mary Bethune’s contribution to education is shown through the cap and gown she’s wearing, but I wanted to know more about Nilda’s research and how she created her vision for the statue.

Nilda Comas (25:31):

Her granddaughter took me to the cabin, the log cabin where she was born and where she lived with her sisters and brothers, 17 in total, with the parents, a two bedroom cabin. And so I saw that, and I read farther about those days and how she picked a book and the little girl took it away from her, from the plantation where her mother and father work and brothers, and said to her, "It’s against the law for Blacks to read," and that stayed with her. All through the night that night she thought to herself, "Well, you know what? I’m going to learn to read, because I love books and I think that’s the difference between Blacks and whites."

Nilda Comas (26:16):

And it just happened that this group of missionaries knocked on the cabin, they just knocked on it about two days after this happened and said, "Any of the children want to learn to read and write?" And she was there and everybody pointed at her because they knew, and so that’s how it all started. After picking about six or eight bushels of cotton as a little girl, eight years old, she used to walk six miles to go to this minister’s home. She would walk all that every day to go and learn how to read and write.

Nilda Comas (26:52):

When she visited Switzerland with Roosevelt, they took them to a garden and there were some bushes of black roses. They gave her a black rose and she wrote a beautiful short essay about the black rose and the interracial garden. Through her life, people gave her after that black roses for her birthday and different occasions. And I noticed at the museum, at her home, in her desk, there’s dried black roses. So I have her holding the cane that Roosevelt gave her, and then on her other hand she has a black rose. It really symbolizes the interracial garden that she wanted. And so I think that it will catch people’s eyes. I’m doing it in black marble from Spain.

Sarah Monk (27:43):

I just want to mention here that Mary Bethune was invited to help draft the United Nations Charter. And as well as her close friendship with Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, she was an advisor to other presidents, including Truman. Another feature of the statue is a pile of books at her feet.

Nilda Comas (27:59):

This bottom is important because it has the two feet and the third leg, which are the books. I decided that we needed a third leg for balancing the weight. You can remember the David having a tree trunk as the third leg, and so I’m using the books. And since she was in education, what took her so far was her education and her desire for every African American child to be educated, and founder of the university, the books would be important. And on the spines we wrote, from her last will and testament, the titles on the spines are from that.

Sarah Monk (28:41):

I then asked Nilda to explain the process by which she got to this stage, with the eight-foot clay model of Mary Bethune waiting for approval from the architect of the Capitol so it can be roughed out in marble.

Nilda Comas (28:52):

The outside of the block and here, this

Sarah Monk (28:56):

Nilda told me after refining her ideas, she made a foot tall plastaline model in her studio in Florida. She brought that maquette to Italy and enlarged it to a two-foot model.

Nilda Comas (29:06):

The distance…

Sarah Monk (29:07):

Then she took a mold of the two-foot model to create a positive copy in plaster.

Nilda Comas (29:12):

… how you say…

Sarah Monk (29:13):

Then a pantograph, an instrument which traces the movement of one pen to produce identical movements in a second, produces a double sized four-foot clay model. Then the process was repeated again to create the final eight-foot model in clay.

Sarah Monk (29:27):

Nilda explains that with every enlargement you lose sharpness, like when you enlarge a photograph and it goes fuzzy, so you have to put in more detail.

Nilda Comas (29:36):

Right here, you see this is flush on the outside of the block. And so this macchinetta is measuring the distance of how far you have to carve. And there are you see, so many points. Yes, they go to the highest point, and then medium point, and then deepest point, and that is the guide for carving.

Sarah Monk (30:02):

Although the delays in Washington meant she was only authorized to work up to the maquette stage, Nilda had taken it upon herself to press on to the eight-foot clay model before she left Italy. This turned out to be very lucky because none of us had any idea that a few months later she would be separated from her work for many, many months.

Sarah Monk (30:25):

The autumn of 2019 rolled on and we entered 2020 talking about Brexit, riots in Hong Kong, and the bush fires in Australia. But these concerns were soon eclipsed by the arrival of a virus in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

Sarah Monk (30:41):

I’m recording the Zoom, are you okay with that?

Nilda Comas (30:45):

Yes, that’s fine, yes.

Sarah Monk (30:45):

It’s really to get an update, because last time I met with you at Cervietti’s, you’ve had the eight-foot model of Mary Bethune in clay.

Nilda Comas (30:54):

Right.

Sarah Monk (30:54):

And then I think you were waiting to hear from…

Nilda Comas (30:59):

See, what’s happened is when I made that sculpture, I still did not have the approval of the maquette.

Sarah Monk (31:06):

Oh.

Nilda Comas (31:07):

I took a chance because I am doing everything as they had me agree at the Library of Congress.

Sarah Monk (31:19):

So you’re…

Nilda Comas (31:19):

so I was very, very worried about it. Even though the money’s there, even though it was a law, I mean, you still have to go through the process. And I’ve learned a lot about the government and politics and going through the process through this, but now he has been approved, only two weeks ago, and it got approved because of Nancy Pelosi.

Sarah Monk (31:41):

Nancy Pelosi is the Speaker of the US House of Representatives and quite a powerhouse in US politics.

Nilda Comas (31:49):

I’m so happy I took the risk and made the big one because it’s in plaster, it’s at the Cervietti Studio, and they can start. And the bronze that is eight feet goes to a park in Daytona and Del Chiaro Foundry is going to cast this sculpture.

Sarah Monk (32:08):

Great.

Nilda Comas (32:09):

And it will go to a new park by the Intracoastal Waterway, which is a beautiful, beautiful place next to a brand new bridge that goes over to the island of Daytona Beach.

Sarah Monk (32:20):

Oh, that will be fantastic.

Nilda Comas (32:22):

Yes, where the university’s main building is, at the end of that street is the Intracoastal, and that’s where the sculpture will go. And they have just renamed the street Mary Bethune Boulevard.

Sarah Monk (32:37):

We’re now in October and we’re in the piazza in Pietrasanta, and we’re still allowed to meet, albeit outside. So I really wanted to find out from you what’s been happening since we last spoke in the spring, because you’re now back in Italy from America.

Nilda Comas (32:52):

Right.

Nilda Comas (32:52):

Well, since the spring, a lot of things have happened in America. There was Black Lives Matter, and this gave more interest towards the sculpture of Dr. Bethune. I am back to work, and I’m working simultaneously in the marble and on the sculpture in bronze. So the marble will go to the US Capitol and the bronze will go to a park in Daytona Beach where she actually founded the university. So I’m going back and forth between Cervietti and Del Chiaro.

Sarah Monk (33:30):

I think you’ve been at Cervietti’s checking the measurements with the macchinettas.

Nilda Comas (33:34):

Yes, because this part is a very important part because all the measurements, a capopunti, everything has to be perfect. And then the artisans will follow, and right now they’re working with the disc and it’s just very, very rough. But those main points are very important, so we remeasured, and also to make sure that we get the prettiest part of the marble.

Sarah Monk (34:00):

Oh, so that’s the stage you’re at at the moment then?

Nilda Comas (34:04):

Now we have decided all of that, and we will keep checking these measurements the next few days, and then all the points will start, which will be about 3,000 points.

Sarah Monk (34:15):

Wow. So you’re working with artisans you’ve worked with before presumably?

Nilda Comas (34:18):

Yes. Marco is the son of Leo. Leo Muti and I went to the Capitol, working in the Basilica, that’s the first time that I actually saw the National Statuary Hall.

Sarah Monk (34:30):

I remember. That’s wonderful.

Nilda Comas (34:33):

It’s his son. Leo’s retired and his son, he’s been working since he was very young, Marco. And then the other fellow, Francesco, is Cervietti’s nephew, which I’ve known also since he was a kid.

Sarah Monk (34:47):

Oh wow. Yes

Nilda Comas (34:50):

Going back, I worked in Pietrasanta on the largest relief in the United States, about 62 feet long. It’s in the Basilica in Washington, DC. I was one of three people who they chose to go to the Basilica and finish the work. And while I was there, CNN came and took some videos of us working, and a Congressman from Florida saw me. I had done his portrait years before when he was the mayor of Fort Lauderdale.

Nilda Comas (35:21):

He saw me and he called and asked if I wanted to have a tour of the Capitol with a curator. So we went and we had a beautiful tour of the Capitol and we went to the National Statuary Hall. And in front of one of the sculptures, Leo Muti started crying. "Leo, what is it?" And he said, "I was 18 years old when I did this sculpture for a sculptor who could not work in marble. And I never thought I would see it again, and much less see the sculpture in a building like this, the Capitol." And so he was crying and I looked around and I said, "Yeah, actually it would be something to have a sculpture that you’ve done here in this building."

Sarah Monk (36:04):

That’s fabulous. So how long would this process take?

Nilda Comas (36:08):

Maybe January. And then more points will be set, so I don’t think I will start working till probably February or so.

Sarah Monk (36:18):

On January 6, 2021, the National Statuary Hall was infiltrated by a 2,000-strong mob attempting to overturn the election results. By March 2021, when I next met Nilda, we’d been living with the pandemic a year. And by the time she landed in Rome, the last direct train to Pietrasanta had left. But ever positive, Nilda told me how she enjoyed a spectacular dawn view from the window of the overnight train she finally took, and it reminded me of her pluck, arriving here 27 years ago with just a handful of letters of introduction.

Sarah Monk (36:52):

What was the first thing you did when you got here?

Nilda Comas (36:55):

I rested. After the two days, and then I was able to go to the foundry and start work right away. And I was quite happy and surprised that the waxes that I needed to retouch were already made. The three large pieces of the eight-foot sculpture in bronze had been cast. And so I saw the three pieces, which are almost finished, finishing the detail and patching all the holes from the casting. And also the top of the hat and the rose, everything has been cast already. So they’re working on the finishing and then they will weld everything together.

Sarah Monk (37:35):

Beautiful. How is it in the pandemic? How different is it working in the studios? You said earlier that they close up and the cleaners come in to make everything hygienic.

Nilda Comas (37:47):

Well, yes. You were quite lonely. I am there all day by myself, maybe with one other person in the large wax room, retouching the waxes, maybe with one helper. But we’re very careful, we wear the masks all day long and our temperature is taken. But I think the biggest difference is a little bit of a loneliness when you work, because before, several artists would be there, but now artists cannot travel, so they’re not there retouching their waxes. At the Cervietti Studio, the same also; we’re working in separate areas by ourselves.

Sarah Monk (38:24):

Are you using new technology when you were in Florida working with the teams over here, do you do it differently than before?

Nilda Comas (38:31):

I actually chose to work the traditional way. We did not use the robot. We used the pointing system with the macchinetta and the crocetto, like it’s been done for hundreds of years. And I decided this would be a good opportunity to have a classical sculpture and do it in the classical way, since it goes to the Capitol in the US. So all those other sculptures in marble were done the same way using this crocetto and macchinetta and pointing system, which is a dying system. Because now it’s being replaced by the robot, and so many sculptors do not know this system. It takes roughly about 10 years to learn.

Sarah Monk (39:13):

And have you been working with artisans you’ve worked with before?

Nilda Comas (39:16):

Yes, I have. The two artisans were actually the sons of artisans that, when I arrive in Pietrasanta, I work side by side and I learned from. And these boys were coming to the studio when they were about 12, and they would work sort of like apprentices. It’s beautiful to see that the tradition was passed on to them.

Sarah Monk (39:38):

It’s a wonderful family feeling here, isn’t it?

Nilda Comas (39:41):

Yes. Yes, it is. Of course, we have specialists in the studio for each stage of the work. First, I use Marco, and that’s when we were doing all the pointing. And now that we are working at a different level, I’m using Luca, and his father was also at the studio for his whole life pretty much.

Sarah Monk (40:01):

How long are you here? And what’s going to be the process from now on?

Nilda Comas (40:05):

Well, right now I am working at Del Chiaro and I will be here until the end of May, so three months, and we should finish the marble sculpture towards the end of April, and also the bronze.

Sarah Monk (40:19):

Finish, finish?

Nilda Comas (40:20):

Yes, finish, finish. And then we will have to take photographs. We are on the seventh step and the eighth step is the inauguration. So the seventh step is finishing and taking photographs for the final approval of the architect of the Capitol. It will not take that long because we’re doing the sculpture exactly like the model, and so there are no changes to it. So it should be just pretty much like a stamp.

Sarah Monk (40:46):

When we were last together in person over here, I think there were a lot of delays that

Nilda Comas (40:50):

Yes. And because of COVID, there’s more delays; and then, the event of January 6th at the US Capitol.

Sarah Monk (40:59):

So what was the impact of that?

Nilda Comas (41:01):

The US Capitol is closed to the public right now. So the official unveiling of July 10th will be moved, because at that time they don’t expect the Capitol to be opened yet. And being that it is Dr. Bethune and she will be the first African American in the National Statuary Hall, they would like to have an inauguration up to par to her importance. And so they prefer that we reschedule at a time when the public can be part of this inauguration.

Sarah Monk (41:33):

How do you feel differently about the project working on it in the light of what we’ve all been going through this year?

Nilda Comas (41:41):

Well, still the project is an enormous achievement to have an African American in the US Capitol. In a way, the delays were good also because I think that time has a healing element. And with Dr. Bethune, I

believe that the more people know about her, the more they realize the importance of her life, and that perhaps she will be more of a unifying person for the United States right now; it’s so divided. And I think they will see her achievements without seeing the color. I really believe that this will happen, and I’m hoping that having her in the Capitol is going to bring some peace too.

Sarah Monk (42:28):

The day before the unveiling of the statue in Pietrasanta on July 10, 2021, I met some of the fundraisers, state legislators, students and staff of Mary Bethune-Cookman University who had flown over from Florida to attend the ceremony. First, I talked with Nancy Lohman, the president of the Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune Statuary Fund.

Nancy Lohman (42:50):

I’m very proud that the state of Florida is bringing the first African American into Statuary Hall, I think it’s fantastic. People of all colors, people of all backgrounds, people of all ethnicities, people of all interests, passions, everyone can find some common ground with Mary McLeod Bethune. I think it’s a unifying event, and I think, in America, we need a unifying event like this.

Yolanda Cash Jackson (43:12):

I’m Yolanda Cash Jackson, and I am a lobbyist. That means that I help Bethune-Cookman University obtain funds and influence. I championed and advocated for the legislation that created the bill that allowed the statue to go forward and go into Statuary Hall.

Yolanda Cash Jackson (43:34):

The racial discussions that are going on in the US, George Floyd, whether or not we take a knee, so many discussions about diversity and inclusion, and here we are with people from across the country, across the world, celebrating this woman of color. So it was a very emotional time.

Yolanda Cash Jackson (43:57):

To have her included means inclusion, that we are finally represented in all aspects of the United States government, that we are influencers, that we’ve reshaped influence, that things will never be the same because we are there. It gives me chills just to think about that. That no longer will little Black girls like myself feel that they’re not a part of what the world sees as the United States of America.

Jacari William Harris (44:33):

My name is Jacari William Harris. I’ve had the honor to attend Bethune-Cookman University. I’m 25 years old, the journey is just beginning. This occasion today is historic. The work that Dr. Bethune did, it is still being spread today. And we are committed to bringing about change and being the change that we wish to see, because change first starts with us inside. Before we can begin to change others, we have to change ourselves, the way we think, the way we process, the way we do things, the way we act.

Sarah Monk (45:04):

Derrick Henry, the mayor of Daytona Beach.

Mayor Derrick Henry (45:07):

For Dr. Bethune to be etched in marble at the epicenter of the Renaissance with the quality of marble that she has been memorialized with, the location, all of the symbolism of it really is extraordinary and reflects her life. She is the model of what we like to be as a community in terms of a spirit of having open hands and open hearts for diversity and difference.

Nancy Lohman (45:34):

We decided as a board to raise an additional $150,000 for a bronze statue that will be made, of course, from the same maquette. So that bronze statue will stand in the middle of a brand new park called Riverfront Esplanade Park in Daytona.

Mayor Derrick Henry (45:51):

The bronze statue will inhabit a main park. I am so excited about it because we see this park as being the place where the entire city will come. This will be the spot that we will come to as a community to rally behind one another, to express that sense of togetherness and that resilience that has always been with us. We will do as we have always done, which is overcome.

Sarah Monk (46:24):

The visitors from the USA have seen Michelangelo’s quarry, the studios and foundry where the marble and bronze statues were made; and now excitement builds for the main event, the unveiling of the statue outside City Hall. The audience gathers and prayers are said. Officials cluster next to Nilda, the mayors of Pietrasanta and Daytona Beach, translators, the heads of the clay and marble studios and of the bronze foundry.

Rev Thom Shafer of Fort Myers (46:51):

… Read with these words, and may these be part of our prayer and part of our excitement for this day. I leave you love. I leave you hope. I leave you the challenge of developing confidence in one another. I leave you a thirst for education. I leave a respect for the uses of power. I leave you faith. I leave you racial dignity.

Sarah Monk (47:20):

July 10th is not only Mary Bethune’s birthday, but also Italians celebrate the start of the campaign which swept up the coast from Sicily in July 1943, finally causing the defeat of Mussolini. The African American Buffalo Soldiers played a big role in this and have always held a special place of affection in the hearts of people in this part of Tuscany.

Valentina Fogher (47:40):

What a wonderful friendship with the United States of America. Thanks to them, we do really feel freedom, democracy, and justice since 1945. And thanks for being together with us.

Sarah Monk (47:59):

I heard emotion in foundry owner Franco Del Chiara’s voice, as he added that his artisans felt honored to be part of this project and to learn about Mary Bethune.

Sarah Monk (48:11):

As if symbolic of the frustrations of the last year, the sheet covering the statue snags, but as people gently tease it, it loosens and reveals Mary Bethune. And there she is, Dr. Mary Bethune, carved in white marble standing 11 foot high. She has a warm smile, kind eyes, and seems to be tilting forward slightly as though listening to someone’s point of view. She wears a cap and gown and in one hand holds a black rose carved in black marble, in the other, a walking stick modeled on the one Roosevelt gave her. At her feet are a stack of seven books with words from her last will and testament carved on their spines: Love, faith, hope, racial dignity, courage, peace, and a thirst for education. She wrote these towards the end of her life, hoping they would be her legacy and inspire the next generation. Carved on the base are her name, birthplace of Maysville, South Carolina, her birth and death dates, and one of her most famous quotes: Invest in the human soul. Who knows? It may be a diamond in the rough.

Rev Tom Shafer (49:23):

I look at how we will see her position her body stature, her eyes, her positioning on the balance on her feet, which talks about both grace and power. And it is amazing to see how one statue can encompass all of this.

Jacari William Harris (49:41):

She has captured her soul and her spirit.

Mayor Derrick Henry (49:47):

Yes, and I can hear angels singing when I look at the statue.

Sarah Monk (50:01):

And then an evening concert at Cervietti’s marble studios to celebrate the life of Mary Bethune on what would’ve been her birthday.

Student Musicians (50:08):

(Singing).

Sarah Monk (50:11):

Arriving early, I find the four student musicians, Kahlil, Hannah, Sarah, and Shanterika, warming up in the car park. The evening’s program is kicked off by Nancy Lohman, chair of the committee.

Nancy Lohman (50:26):

And of course, the star of the show, the person that we love so much with all our hearts and the person who has made all of our dreams come true…

Sarah Monk (50:35):

Nilda Comas gets a huge cheer and makes a short speech of thanks.

Nilda Comas (50:45):

…

Sarah Monk (50:46):

There is music and readings and a lot of gift giving and thanks. It has been a team effort and Nilda’s close relationships with the studios of Pietrasanta have certainly paid off during the challenges of the last few years.

Nilda Comas (50:59):

… Franco Cervietti, …

Sarah Monk (51:04):

Giancarlo Buratti’s clay studio, Franco Cervietti’s marble studio, and the bronze foundry run by Franco Del Chiaro. One says, "I’m just an artisan, I’m not used to this."

Franco Del Chiaro (51:14):

To receive this gift, I was not prepared, and I am astonished. Thank you. Thank you. You are all way too kind. I told you yesterday when you…

Sarah Monk (51:26):

Some of the visitors from the USA take turns reading from Mary Bethune’s last will and testament.

Alumni of BCC (51:31):

Truly, my worldly possessions are few yet, my experiences have been rich.

Jacari William Harris (51:40):

Yesterday our ancestors endured the degradation of slavery, yet they retained their dignity.

Sarah Monk (51:48):

And then before the birthday cake shaped like the books at the base of the statue is cut, the alumni of Bethune-Cookman University come up onto the stage to sing the university song.

Alumni of BCC (52:21):

(Singing).

Mayor Derrick Henry (52:30):

We are beyond elated and appreciative of Nilda and of the people of Pietrasanta for blessing us with such a beautiful gift. And though Dr. Bethune had long passed, long before I was born, today, I felt like I was in her presence.

Alumni (53:08):

(Singing).

Sarah Monk (53:12):

And so the big day over, Mary Bethune’s statue was shipped to Florida and went on view in Daytona Beach before taking a short tour to her birthplace in Maysville, South Carolina. Finally, it will make its way to the US Capitol for an inauguration in the summer of 2022.

Nilda Comas (53:34):

I’m so lucky and so blessed to have such great support behind me. Because Del Chiaro and Cervietti, they know my hand, they know how I like things. And I’m a little bit fastidious sometimes about things, because I like everything like I did it, and there’s really not a lot of room for changes, or anything else. But they are so proficient and so good at it that they are able to follow that, instead of making changes or going on their own to say, "Okay, this should be like this or like that," they’re following exactly how my creation was, so I’m very happy with that.

Nilda Comas (54:22):

I think anything that you get up every day and you do all day, you get good at it. Doesn’t matter what it is. If you always did this every day, get up and do this, you’ll eventually find your way with that.

Sarah Monk (54:52):

Our thanks to Nilda Comas. You can see her work on her website, NildaComas.com. Thanks, too, to the many contributors whose details can be found on our website, MateriallySpeaking.com, along with some photos of Nilda’s project, creating the statue of Dr. Mary Bethune. Special thanks to my sound recordist, Andrea Gobbi and editor Guy Dowsett. If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, please follow us on Instagram or subscribe to our newsletter on our website to hear about new episodes.