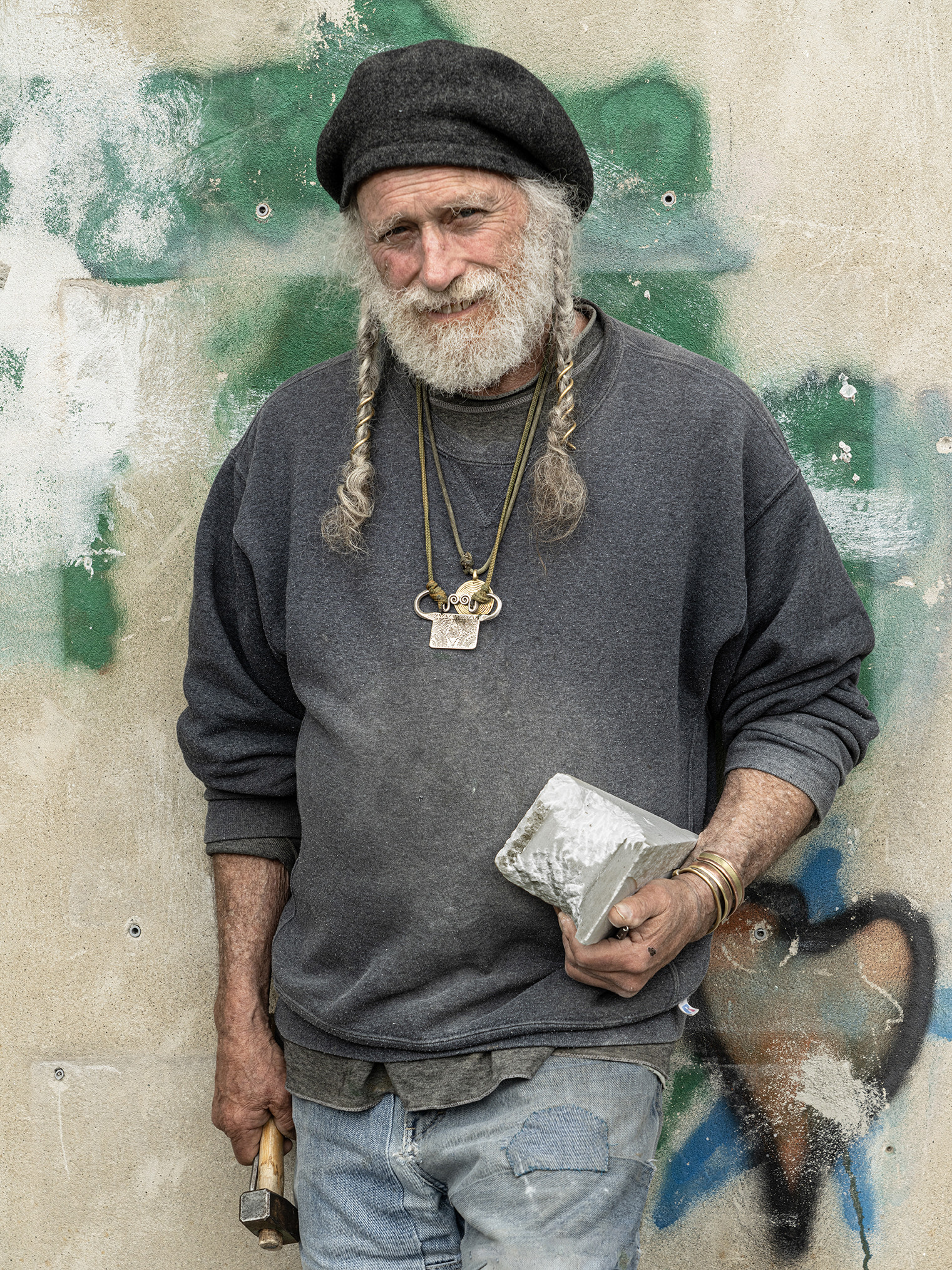

John Fisher. Photo: Gail Skoff

Originally from Oregon, John moved around America a lot as a child. Although he was not formally schooled as an artist, he received his education at a young age while travelling with his family through Europe and the Middle East. There he took in many of the great works of antiquity.

John Fisher, Girl in the shower. Photo: Gail Skoff

John came to sculpture in his thirties from a background in painting, and very quickly began carving monumental pieces which he was able to sell. It was at this time that he experienced a revelation when he began to imagine how stone carvers worked in the past.

Although this technique is much less practised nowadays, he believes that for thousands of years sculptors worked without eye protection. They discovered what John refers to as profile carving. John describes himself as a direct, flexible, profile carver.

John Fisher, Ever Oasis, marble, Brookgreen Gardens, North Carolina

The first piece John mentions is a big reclining figure which earned John enough money to allow him to come back to Pietrasanta and work. Recently the owner of that piece died and John was able to buy it back in an auction.

John standing with one of his sculptures in Querceta Cemetery. Photo: Gail Skoff

John also tells of the gravestone he carved which is in the cemetery of Querceta, near Pietrasanta which is a Pieta of 5 life-size figures.

John Fisher, Lovers, marble. Photo: John Fisher

Another piece, a pair of lovers, John carved from a special piece of marble he had kept for 16 years. As he was carving the embrace he had a moving experience as he felt them pushing themselves into each other, as though they couldn’t get close enough.

Now John divides his time between the Redwood forests of California and Pietrasanta - drawing inspiration from the world around.

John Fisher, Angel of the Quarry Man, marble.

He acknowledges a great debt to the cavatore, the quarrymen. Without quarrymen, artists don’t have the material to work with.

Photo: Gail Skoff

John Fisher, 2024. Photo: Gail Skoff

Credits

Thanks to Gail Skoff for collaborating on John's episode and for the fantastic photographs.

Gail Skoff, gailskoff.com – instagram.com/skoffupclose

Producer: Sarah Monk

Producer/editor: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Chiano 1609_44 mixes, Dan Skinner _ Adam Skinner

I have a great debt to the cavatori, the quarrymen. And so the angel at the La Capella is the angel of the quarrymen, and up there at Adzano is also the Madonna of the quarrymen. Without the quarrymen, we artists don’t have material to work with. So I’ve always felt this huge debt to those men who’ve sacrificed their lives, put themselves in danger so that we can have stone.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of Materialise Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, Mike and I are in Pescarela Studios between Pietro Santa and Carrara, meeting John Fischer. Although not formally schooled as an artist, John received an education at a young age while traveling with his family through Europe and the Middle East, where he took in many of the great works of antiquity. He came to sculpture in his thirties from a background in painting and very quickly began carving monumental pieces.

Sarah Monk:It was at this time that he experienced a revelation when he began to imagine how stone carvers worked in the past. Although this technique is much less practiced nowadays, he believes that for 1000 of years, sculptors worked without preliminary drawings, essentially inventing the form as they carved. Now he divides his time between the redwood forests of California and Pietra Santa, drawing inspiration from the world around. We ask John to introduce himself.

John Fisher:I’m John Fisher. I’m 73 years old, and I’m a sculptor, painter, artist. I’m a direct, flexible profile carver. That means I don’t make models. I don’t make preliminary drawings.

John Fisher:I don’t do anything except stand in front of a block and carve it. Flexible because things change. And profile carving is the technique that I use that I think people carved that way for 1000 of years.

Mike Axinn:And what does it mean exactly?

John Fisher:That’s what I asked myself when I got here. I said, how did they carve back then and not go blind? Because I was just showering myself with stone, and it was hitting me in the face and cutting me on my arms, and I come home a bloody mess. I said, this can’t be right.

Mike Axinn:You say it’s been done for years. Is that a concept that has been known or spoken about amongst other sculptors?

John Fisher:As far as I can tell, I’ve never seen anything written about it or any mention of it in any book or other than what I say to people. For 1000 of years, nobody had eye protection. Now everybody uses eye protection because they shower themselves with marble all day long without thinking for a moment that nobody would have ever carved that way ever in the past. When you’re carving profile, you’re looking behind your chisel. Everybody here looks in front of their chisel.

John Fisher:The stuff in front of your chisel is the waste material. That’s the stuff you’re taking off. Stuff that you’re leaving, you see underneath the chisel. So I’m only carving lines, And a line is either correct or it’s incorrect. So when I’m looking at a profile, I see the line that’s there.

John Fisher:I judge it whether it’s correct or incorrect. If it’s incorrect, I put my chisel on that line and make a difference. Change it. You’re looking right behind your chisel, and you’re just carving that line.

Mike Axinn:There’s that classic concept, I think, from Rodin that the sculpture is inside the stone, and you just have find it. Do you agree with that?

John Fisher:Yes. I agree with that. I first take off approximately 30% of the weight of the block, creating an abstract sculpture. When that abstract is strong, even from a distance, then any image I pull out of it will still retain the abstract while adding a story.

Mike Axinn:Do you know what you’re gonna carve in advance?

John Fisher:I never know what I carve in advance. My great teacher said that any idea that comes out of your p brain will be trite and superficial, but the ideas that are born through the process come from a deeper well, come from the subconscious, not the conscious.

Mike Axinn:And that’s also what tells you when you’re on the line?

John Fisher:That line is when I start to see an image and decide that that’s the one I’m gonna carve, then it’s like when you see an image in a cloud. You don’t see the whole image, but you see some parts better than others. So when I start carving, I just start carving at the parts that I see well, and then I can make decisions. And those decisions lead to more decisions and more decisions and more decisions.

Mike Axinn:Tell me a little bit about where you come from. Where were you born, and where did you grow up?

John Fisher:I was born in Eugene, Oregon, but at 3 months, we moved to Indiana. 3 years later, we moved to New Jersey. 3 years later, we moved to Oklahoma. And I went to high school in Southern California, Claremont, California.

Mike Axinn:And how did you become an artist?

John Fisher:My father’s an archaeologist. He’s a historian and a professor of linguistics. And at age 12, he took the whole family on a sabbatical throughout Europe and the Middle East. So at age 12, I walked through the Lion Gate in Mycenae. I stood in the Parthenon.

John Fisher:I went to Istanbul, Beirut, Damascus, Beylabec, Jericho, Jerusalem, came back through Naples, saw Pompeii, went to Rome, saw the Sistine Chapel, the Pieta, the Moses, went to Florence, saw the slaves, the Medici tomb. Then we spent 6 months in Paris where every Sunday, we went to the Louvre. So I had a huge art history experience at a young age. Well, a lot

Mike Axinn:of 12 year olds would have been bored out of their minds.

John Fisher:Yeah. But you can’t be bored by the Parthenon or the Mycenae lion cake. Come on.

Mike Axinn:They’re fabulous. Is there a transformative event in your life that informs your work as an artist?

John Fisher:You know, I just have always been an artist and always will be an artist. I left home at 18 and started supporting myself with watercolors. I didn’t find marble till I was in my thirties, mid thirties, and then I came almost immediately to Pieta Santa. And after a few pieces, I got tired of carving small sculptures, and small sculptures never really changed my life. And so I came back and carved a monumental piece, and that sold for a lot of money, and it made it possible for us to come back here and live for 20 years.

Mike Axinn:You realized you wanted to be an artist at 12, and you effectively did it, but there were changes in the media with which you worked.

John Fisher:Well, I think it was good that I started with drawing and painting because that’s where you learn all your profiles. You learn how to draw someone from every possible point of view, and every edge is a profile.

Mike Axinn:Something you told me that I found very moving, if you feel comfortable talking about this, was your relationship with your daughter and the fact that you read to her, but that you now actually do drawings for the books that she

John Fisher:Well, it’s a great honor to collaborate with your daughter, but she’s gonna be a better illustrator of her books than I am.

Mike Axinn:Also, when she was growing up, you used to read to her for 4 hours a day.

John Fisher:It was time that I was able to bond with her. We read to her early in the morning before breakfast. We read to her after lunch. We read to her in the afternoon before dinner and after dinner. And I wanted her to read Siddhartha.

John Fisher:I wanted her to read the Count of Monte Cristo, and for her to have that knowledge.

Mike Axinn:So you’re a man who uses his hands, but there’s a tremendous intellectual foundation.

John Fisher:I don’t have that much education. I just went to high school. So I never continued on my education. Once I knew I was gonna be an artist, that’s really the only thing I was interested in.

Mike Axinn:So can you talk about 3 of your works in particular that you’d like to share with us?

John Fisher:Well, that first big sculpture enabled us to come back and stay here for a long time. It’s a reclining figure. In many ways, it’s abstract. It doesn’t make any sense. It’s in a position that you couldn’t necessarily hold.

John Fisher:The pose is very strange. I’m also a modern artist, so I’m not interested in doing pure classical stuff. Another one is there’s a gravestone in the cemetery of Cocheta, and I did a pieta. It was 5 life-sized figures, and I just looked into the stone, saw my image, and carved it. This way of carving is extremely fast in marble.

John Fisher:I had a block of marble I’ve been holding on to for 16 years, and I decided to carve 2 lovers out of it. I’ve carved lots of sculptures of just single women, single men, but I haven’t carved lovers. So I started at the top because if I didn’t have the embrace, I didn’t have a sculpture. I did the heads, and then I got the shoulders. I worked my way down the block to the feet.

John Fisher:But still, I only took 4 months to do it. There was a moment there where I was carving the 2 figures, and they’re pressing themselves so tightly together, you know, when you just can’t get close enough. And it almost looked like they were moving. I felt them pushing against each other as I was carving them. That’s happened so many times that I don’t know what I’m doing, and it’s just creating right in front of my very eyes.

John Fisher:That doesn’t happen when you make a model. Where are most of these pieces right now? Well, there’s, I think, 22 sculptures in this area, the Vercellia, in public places. Fantastic.

Mike Axinn:Anything else you’d like to add?

John Fisher:I have a great debt to the cavatori, quarrymen. And so the angel at the La Capella is the angel of the quarrymen, and up there at Adzano is also the Madonna of the quarrymen. Without the quarrymen, we artists don’t have material to work with. So I’ve always felt this huge debt to those men who’ve sacrificed their lives, put themselves in danger so that we can have stone.

Sarah Monk:So thanks to John. You can see his work on his website, johnfishersculpture.com, or on Instagram at giovannipescatore 51. As always, you can find photographs of the work discussed today on our website, materially speaking.com, and on Instagram at materially speaking podcast, and thanks to you for listening. If you enjoy Materially Speaking, please join our community and sign up to our newsletter on our website. Then we can keep you up to date with future episodes and occasional special events.