Alvisé Boccanegra, 2022

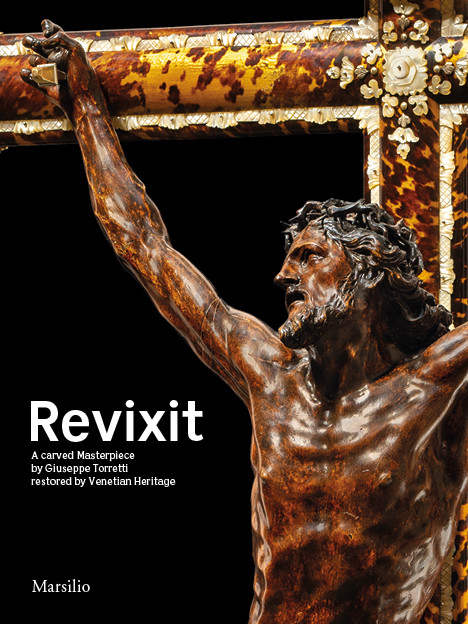

In the third of our Venice series, Mike and I are meeting furniture restorer Alvisé Boccanegra who trained in restoration in the workshops of the Church of San Marco. He tells how he repaired a crucifix after Venice flooded in 2019.

Alvisé’s workshop is in the heart of San Polo on the ground floor of the building where he was born. Inside it smells of wood and linseed oil and there are neat shelves of brightly coloured powdered paints and a large selection of jam jars with oils and waxes.

Over the years Alvisé has collected samples of wood which he keeps in his wood library. This helps him compare the density, and other features, of different woods from all over the world and understand better how to work with them.

Alvisé tells of a very special project restoring a crucifix – a masterpiece by Guiseppe Torretti – which was found floating around the church of San Moisè after the aqua alta (high water) of November 2019. As he says in a Tweet:

Grazie a #VenitianHeritage è stato restaurato il crocifisso di #GiuseppeTorretti (XVIII s.) della chiesa di San Moise, danneggiato durante l’acqua alta eccezionale del 12.11.2019. Ora è esposto nella cappella di #PalazzoGrimani fino al prossimo febbraio #acquagranda #Venice pic.twitter.com/5kmQJvyxLd

— MuseoPalazzoGrimani (@PalazzoGrimani) November 14, 2020

This catastrophic flood brought the second-highest waters since records began in 1923. It submerged St Mark’s square, caused enormous damage to homes and artworks, and left two people dead.

The photograph of this statue immersed in water was widely shared and became a symbol of the need to preserve the special, and often sacred, beauty of Venice.

Alvisé explains the delicate procedure, restoring materials that are no longer frequently used like mother of pearl and tortoiseshell.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound recording, edit and design: Mike Axinn

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Flying Colours 3703/4, Christopher Slaski

Alvise (00:29):

This crucifix has been found floating on the high tide two years ago when the Aqua Granda, we call the Aqua Granda, is this big high tide that happens on November of two years ago. This is a piece I’ve done completely. It is a crucifix from the 18th century, carved by Giuseppe Torretti, who was a master artisan in Venice. It’s very peculiar because the cross is completely covered by tortoise lamina.

(01:05):

This crucifix has begun the symbol for the floating because all the newspapers also outside of Italy was reporting the shot of this crucifix floating on the water.

Sarah (01:20):

Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists and artisans tell their stories through the materials they choose. In the third of our Venice series, Mike and I are meeting furniture restorer, Alvise Boccanegra. It’s easy to get lost in Venice, but we enjoy the rewards finding quiet squares, a hidden walled garden, a jazz group rehearsing in a front room. After crossing the Rialto Bridge, we weave through the streets of San Polo until we eventually find Alvise’s workshop on the ground floor of the same building that he was born in.

(01:53):

Inside, it smells of wood and linseed oil. There were busy work benches, neat shelves of brightly colored powdered paints, and a large selection of jam jars with oils and waxes. On the back of the door is a dark board. We’ve been drawn to Alvise because of his work restoring a crucifix, which was found floating in the church of San Moisè after the high water in November, 2019.

(02:18):

This catastrophic flood bought the second highest waters since records began in 1923. It submerged St. Mark’s Square, caused enormous damage to homes and to artworks and left two people dead. The photograph of this crucifix immersed in water was widely shared and symbolize the need to preserve the special, and often, sacred beauty of Venice. I asked Alvise to introduce himself.

Alvise (02:45):

My name is Alise, Boccanegra is my surname. My job started 17 years ago with the Church of San Marco in the laboratories of conservation for wood sculptures. And there, I met my grand master, Maximilian, who teach me all the techniques for the old temperas, with egg tempera, milk tempera, casein tempera. And he also introduced me in the carving of wood, and I worked for them for seven years.

(03:20):

Then, I decided to open my workshop. At the beginning, my own workshop was not easy to start because my work works on, you know, you have to trust in me. So, you have to make some little works not so beautiful just to introduce your way of doing to antique dealers and private collections and so on. It takes a long time to make it a real work to live with.

Sarah (03:56):

I can understand, because they’re entrusting you with things that…

Alvise (03:58):

Yeah.

Sarah (03:59):

… you can’t mess up.

Alvise (04:00):

At the beginning, you have to try. I was going around in the city, and asking for the antique dealers, "Do you need a restorer?" "Do you need something?" "Yes. Work on this piece, and then, we see how it’s done". Time by time, I found my clients, the people who trust me.

(04:27):

Anyway, it’s a journey, my work is a journey. Very long, every day, you learn something more, so you never… And your growth, you are always looking for new techniques to understand new ways of doing your job. Also, because wood items not always have a nice life, because it’s just from the 20th century that the people start to understand that the good sculptures and good furnitures were something important to preserve.

(05:11):

Before, they were always painting over, or just throwing it away. The frames were preserved. The stone sculpture were preserved, but the wood furnitures and the wood sculpture was just used. And when it’s over, they just throw it away.

Sarah (05:28):

Isn’t that interesting? So, you think it’s only in the last century, really…

Alvise (05:32):

Yeah.

(05:32):

… that people have appreciated.

Sarah (05:34):

Just maybe in 150 years, something like that. No more. Except for the big church furnitures, something like that was preserved anyway. But the furnitures in the house of the people, the sculpture that people… Also, the sculpture of the churches were not preserved. Just painted over. When it changed the time, changed the styles, and they paint it for make it different for the new style for the new period.

(06:03):

And so, when we work on this items, they are always full of problems. And so, every day, you have to learn something to find their way out.

(06:17):

You’re Venetian?

Alvise (06:18):

Yeah.

Sarah (06:18):

So, where were you born?

Alvise (06:20):

I’m Venetian, but I was born in Asolo, near Treviso. But I came here that I was like one year old living here in the second floor.

Sarah (06:31):

Of where we are standing now?

Alvise (06:33):

Yeah. Yeah, yeah, exactly. After I went out of my house, and I’ve been living always in Venice, but I’m somewhere else. Then, I came back into my family house when I was 25, 26 years old, and I’m living here until that time.

Sarah (06:52):

Gosh. And so, what’s it like living in Venice, being brought up in Venice?

Alvise (06:57):

It’s very peculiar. Venice is very different from everywhere. There are no cars, you are always by walking. When somebody ask me, what’s the different of living in Venice, I always use this story to make understand, there is not your house. The world city is your house. Because when you’re walking through the city, you are always by feet and you always met people, and everything you do by day, by night, when you are younger, when you are older and so on, every part of the city has memories of your life.

(07:41):

I feel at home when I just see the lagoon. It’s just like home. I don’t need to come back inside my house. Everything is familiar. Everywhere is familiar. Because you spent your life in all the streets, in all the squares. One funny thing is if you want to go from one point to another in this city, you are never in time, because you met everybody. So, you have to stop to talk to everybody, everybody knows you. "Hi, how are you? Where are you going?" So, you’re always late always. Always.

Sarah (08:16):

Not just cause you get lost.

Alvise (08:17):

No, no, not because I lost-

Sarah (08:19):

Like you don’t get lost. Can we go back to what you did until you became a craftsman?

Alvise (08:25):

Right before beginning, I was studying for chemistry for restoration. I just studied for a few years, and it has been useful for me, because it gave me a way to understand how material interact with the external sunlight, rain, and how it gets ruined. I was a computer techni… Hardware and software, going house by house, working on computer. Yeah. After, I decided it was not my way, I don’t like it anymore.

Sarah (09:01):

And is it a family thing, this work?

Alvise (09:03):

My grandfather was an artisan of Stucchi and Marmorino. You know Stucchi? The decoration made of gypsums? And the Marmorino is the finishing of the walls made by lime and powder of marble, really ancient technique, used also by Romans and so on, because it’s very durable and it’s very resistant to external elements like sun and rain and so on. My grandfather worked for big architects in Italy, and not only in Italy. But when I opened my own workshop, I decided that I have to interact only with one element. Just wood was my choice.

(09:59):

And so, I started my way on to find all the techniques, and only about what have been done on wood, all the techniques of the painting on wood, the gilding on wood. At the beginning, my family wasn’t so happy about that. You know, "You wrong everything. Artisans doesn’t live anymore". I said, "No. It’s my way. I like to work on… It’s my way. I like it". And then, I started on furnitures, because I was only working on sculptures before. Sculptures, I mean, frames and chandeliers, everything made of wood, but painted or gilded. Not just wood, like a furniture.

(10:50):

The materials you use on the wood is different, because to carve wood, you need wood that can be carved. I’m sorry.

Sarah (11:00):

Oh, you got to hammer, it’s a ring tone.

Alvise (11:04):

Yeah.

Mike Axinn (11:04):

It’s a great ring tone.

Alvise (11:05):

It’s mine. Nobody has it.

Mike Axinn (11:07):

Soft wood.

Alvise (11:12):

Now, if you have to carve wood, you need a wood that can be carved. When you don’t need it to be seen, the wood, so you have to paint it over, or to make a gold gilding, you use softwood like cirmolo. I think it’s Swiss pine, that is used almost in the north Italy. Then, you can use LimeWood that is really soft. It’s used for making carvings with little details.

Sarah (11:47):

So, these are the woods that are softer. And if you’re not going to see them…

Alvise (11:50):

Yeah.

Sarah (11:50):

… at the end, if you’re going to paint them, then, these are the easier ones for carving.

Alvise (11:55):

Also, the paper wood, poplar, is pioppo in Italiano. pioppo is very useful also for the sculptures that need to be bring in procession, because it’s very light wood. So, you can find that the crosses of the crucifix made of poplar because it’s very light. Other way, if you have to carve wood that has to be seen like the furnitures of the churches, and so on, you have to carve hardwood like walnut.

(12:26):

In Italy, quitely, everywhere is walnut. If you go to Austria, you find chestnut. In France, it’s oak. Also, in the north Italy, northwest of Italy, you can find oak and… Chestnut is not really a hardwood. It’s between. It could be hard and not. It depends on where it grows.

Sarah (12:47):

Really? So, the same wood? The same tree will be different?

Alvise (12:50):

Yeah, yeah. All the woods is like that.

Sarah (12:50):

Really?

Alvise (12:54):

Yeah. If they grow very slow, maybe they don’t have so much sun, or not so much water, if they grow very slowly, the wood would be very compact. And so, it becomes very strong, very hard. And if a tree grows very fast because all the condition is good, and the wood would be a little bit more softer. For all the woods, it’s the same.

Sarah (13:23):

So, I noticed in the corner, you have what looks like a little book case. Within step books, there are little slices of wood.

Alvise (13:31):

Yeah.

Sarah (13:32):

So, can you tell me about this?

Alvise (13:33):

It started from… the idea comes from my master. Because it’s not easy to understand which wood the items you are working on is done. So, the easier way to understand it is to compare it. You have your item on restoration and you have a piece of wood, you exactly know what it is, and then, you compare the veins and the grain, and you can understand what kind of wood is it.

(14:08):

And from there, started my book case, and I started to collect them… All the woods, I found by myself by going outside in the countryside and so on. And then, I start asking two friends of mine, maybe they’re going to Brazil or in Africa, and I told them, "Bring me a piece of wood from where you go". And so, I start collecting also exotic woos. And some of them are so strong that you have to change the blade of your chisels because it gets broken. You cannot carve with normal chisels.

(14:52):

Some of them, the exotic ones got sand dust inside the grain, because they live in very sandy ground.

Sarah (15:03):

That’s amazing.

Alvise (15:05):

Yeah. And another different between sculpted and varnished wood is all the tools you use to work on them, because the furnitures needs a lot of tools, and for the restoration of ancient furnitures, not contemporary, is quitely everything made by hand. There are no machines that can help you. So, I’m going to buy and look in on the internet to find tools also from the 19th century, wood planes and chisels.

(15:43):

There are some of them very particular that you have to have them to make that job. You can’t do in other ways. So, I’ve been looking for wood planes all over the world. I just bought one from Australia, yeah, because nobody use them anymore. Just me. Everybody want them because they are collectibles, because very rare, very particular, and they want the tool just to collect it. Other way, I needed to work. So, I’m looking for them for a good price.

(16:18):

And in Italy, in Europe are very expensive, because all the collectors want it. So, I found it out in Australia for a very cheap price. It took some month to arrive, but now, I got it. The tools are the same everywhere. A little bit different is for the China and Japanese woodworking. I’ve been in Japan a few years ago, and I’ve been looking for some of them tools, because there are very, very good tools, but they has to be used in different way of the European tools.

(16:53):

Just stupid example, the European saw, you use it pushing, and other way, the Japanese saw is used pulling. Because there is different concept, it’s different way of working, because quitely, all the artisans works sitting, and so, they use different movement. We work standing, so our body is the weight to move the saw. Instead, they use the muscle of the back to pull the saw. Because furnitures, you got a lot to learn about the varnishes. You can find quitely everything for paintings, but for furnitures, it’s very difficult to find out something, because nobody wrote down nothing in the years, in the centuries.

(17:40):

I’ve been doing my own researches and I found out a book of an artisan of the 18th century from Tuscany that wrote for a duca, all the receipt for the varnishes for making something, so on, but it’s very hard to understand. And often, the materials, the varnishes that he used, you can’t find it anymore.

Sarah (18:16):

Can I ask you, maybe to talk about one of the pieces that you’ve done in the last few years.

Alvise (18:22):

It is a crucifix from the 18th century carved by Giuseppe Torretti, who was a master artisan in Venice. It is very peculiar because the cross is completely covered by tortoise lamina.

Sarah (18:42):

Tortoise shell?

Alvise (18:43):

Yeah. But it’s not tortoise shell. The tortoise shell has worker to be laminated. It’s very, very thin.

Sarah (18:53):

I’m very ignorant.

Alvise (18:53):

Stretched.

Sarah (18:54):

Oh, okay. They stretch. So they-

Alvise (18:55):

So like in jewelry, you have a metal machine, and you have to pass through the… Is the machine-

Sarah (19:01):

Like a roller machine?

Alvise (19:03):

Yeah. To make it thinner. It’s the same work but with the tortoise shell.

Sarah (19:08):

Wow.

Alvise (19:09):

I tried because I found some pieces of tortoise and I tried to do it myself, because I want to understand how they do that. Because if you know how they do that, you can restore it.

Sarah (19:21):

So, this piece was floating in the lagoon?

Alvise (19:23):

No. It was floating inside the church when the aqua granda, we call the aqua granda, this big high tide went inside the church. Also, inside here, there was 25 centimeters of water.

Sarah (19:35):

Oh gosh. Wow.

Alvise (19:36):

Yeah. It was very, very high. You see, there is a big step for coming here. Two steps to go outside. So, if you were walking, the water was like here.

Sarah (19:46):

So, this was 2019, November, 2019?

Alvise (19:49):

November, 2019, yeah.

Sarah (19:53):

Yes.

Alvise (19:54):

2019, the 13th of November.

Sarah (19:56):

Just before the pandemic.

Alvise (19:57):

Yeah.

Sarah (19:58):

So, how did you approach this project? Was it just you working on it, or was it a team?

Alvise (20:03):

I’m always just me. I’m always by myself. I’m the only one working inside here.

Sarah (20:09):

So, this crucifix, why did it need restoring?

Alvise (20:12):

This crucifix has begun the symbol for the floating, because all the newspapers also outside of Italy was reporting the shot of this crucifix floating on the water. Here in Venice, we got like, that I can remember, four or five crucifix made of tortoise. But it was used in that century to make frames and mirrors made of this lamina of tortoise. And behind the tortoise is gilded with gold leaf.

(20:46):

So, in the white spots of the tortoise, you see the gold behind shining. This is a part of the edge of one branch of the cross, and we have the molded wood. Then, on the molded wood, we have a paper glued directly on the wood, and then, we have the shaped tortoise shell. To shape it, is has to be boiled in water, and then, it becomes very soft like a tissue. And you put it over this mold wood, and you let it stay there until it’s cold. And when it is cold, it preserve the shape.

(21:31):

Then, you have to gild the inside of the tortoise, but not using the same glue that you used for the paper. I used, what I think it was been used in the original one, and it is a glue called oleo resina, that it is oil and pine raisin seeds.

Sarah (21:54):

Linseed oil.

Alvise (21:55):

Linseed oil. This is a very strong glue for the gilding. It was used also for the gilding of iron and the gilding of marbles and stones. And then, you have the two pieces, the tortoise gilded on the inside, and the wood with the paper. And then, you glue them together with the bone glue that it is the most used in history glue for furnitures and wood. So, you have to keep the bones at like 50, 60 degrees for a very long time until the glue from the bones, the proteins from the bones comes out and fill the water.

(22:39):

Then, you have to reduce the water and you have to glue. And it is really strong like a stone. All the edges are made of mother of pearl. These are all pieces of mother of pearl covered and glued on the cross and fixed with nails of silver with a spearhead.

Sarah (23:03):

Can you tell me a little bit about mother of pearl?

Alvise (23:06):

Mother of pearl is a shell. This one… was particularly difficult to work on that, because some little pieces, few pieces were missing, and so, I have to make the new one. And today, you can find only very, very thin mother of pearl shells.

(23:27):

So, I’ve been going through antique dealers to find old stuff made of mother to cut them and make the new pieces. It’s not easy to find it very thick.

Sarah (23:40):

Thick. And why is that? Do we know why it’s thinner now than it used to be?

Alvise (23:44):

I think that the very thick one are protected. Like the tortoise, you can’t work it anymore. You have just to work on something you find already on antique dealers and so on.

Sarah (24:00):

So, how big is it? Just to get my head round. How big was the crucifix?

Alvise (24:04):

Oh, it’s two meters. All the cross, not the Christ, but all the cross was two meters and 60. Yeah. Two meters and 60 centimeters high. And the Christ, instead, was like one meter 60. One meter, 40. Something like that. The Christ was covered in the soft pinewood I told you before, and it is completely empty inside to make it lighter, because it is a processional. It has to be carried. And also, the cross is empty inside, and the Christ is made of a lot of slices of wood to prevent the moving and the cracking of the wood.

(24:55):

And the finishing is a varnish, brown red varnish, to make it appear the wood like buxus. Buxus is a precious wood used for smaller Christ with a very beautiful color. Boxwood maybe is the English word.

Sarah (25:16):

And what sort of condition was it when it came to you?

Alvise (25:19):

Before we went to the church and the Christ has been putted in a second floor, not warmed, just with the outside temperature, there was no… Nothing to warm it. And it’s been left there for six months to dry up very slowly, because if you make it dry very quickly, the wood can move, and the Christ can crack everywhere, or the cross can bend. Then, we went to the church, we bring it here by boat. And little by little, just split together the broken parts, and then, start to understand how to work on the tortoise. So, you have to understand how to clean it, how to make it shiny again.

(26:21):

Then, all the mother of pearl pieces, thousand of them, from the front, also, behind, everywhere is made of mother pearl. And then, one by a one, has been cleaned and polished it again. I collaborated with the jeweler to clean up and to make new nails, because some of them were broken, and also, because they have equipment to clean up the silver in the right way. Then, I started to make the new parts, the missing parts of mother of pearl, working with…

Sarah (27:04):

Chisels.

Alvise (27:04):

No chisels. These are files.

Sarah (27:07):

Files. Yes.

Alvise (27:08):

Yeah. Because… Before you sew it, and then, you have to carve it with the files. You cannot carve it with the chisels. It’s a jewelry tools.

Sarah (27:21):

And that was for making the holes for the nails, perhaps, was it?

Alvise (27:24):

For the holes on the nails, and also, to make the very small carving on the single element. You have to find out the way to do it.

Sarah (27:36):

And what were the missing parts? Did some bits go missing completely?

Alvise (27:40):

Some piece of mother of pearl was missing, but few of them. And on the Christ, a finger on one hand was broken, and the contact with the high tide, with the water melted the glues. So, the lower part, the one that has been for a longer time contact through the water, the glues were melted. The furniture that is used to make it stand was completely destroyed, because the church where the crucifix is also today is the San Moisè church, and is very low on the sea level.

(28:24):

So, every year, the high tide flows inside. Not so much to make the Christ fall in the water, but the furniture, every year goes under the water. So, it was really damaged. The decoration of the basement of this furnitures was completely missing or rotten. So I needed to make new one with the same shape, same wood, and same techniques to make the furnitures come back to be used. Everything has been paid by the Venetian Heritage.

Sarah (29:03):

How did it feel? What was the experience of doing this restoration?

Alvise (29:06):

Very beautiful. Very beautiful. Because I have been… Took a long time, months of work, and trying to do something you have never done before is always very exciting for me. And to improve myself with tortoise and the mother of pearl has been very interesting. I learned a lot.

Sarah (29:32):

Was this during the pandemic that you were doing it, so…

Alvise (29:35):

Yeah. No. Because for me, it was quitely easy because I live on the second floor over my workshop, so I don’t have to go out of my house to work. So, I just was at house, at home closing up with the lockdown, so on. So, I came down and work in my workshop, and I came back to my family.

Sarah (29:57):

Did you love the piece?

Alvise (29:58):

Yeah, of course. [inaudible 00:30:01]in exposition, a show for one year, almost one year has been in Palazzo Grimani to be seen by visitors. All the restored crucifix, and also, this publication has been done. And then, last November, the 13, two years after, the Christ came back to the church, and there has been a presentation with all the priests and the church. Very nice.

Mike Axinn (30:34):

I have a question, which is, what are people thinking about now? What kind of concerns do you have with the people in your community?

Alvise (30:42):

Venice is like a museum now. So, it’s not really in a good condition. It’s not so easy to live here. In one way, it is a perfect place to live, in another way, it’s quitely impossible to live here, because the services are missing, and so, you have to find your way of let it work. You have to manage to… So, also for my work, for the things I use, materials that I use for my work, there is maybe one shop in all the city where I can buy the bone glue, and it’s very expensive.

Sarah (31:30):

And the water level, how and what is being done to make sure there’s no more outer water, or is it…

Alvise (31:38):

There is the MOSE. The MOSE is this… It’s just very particular in word, paratia. It’s like a floating doors that close when the tides gets high.

Sarah (31:56):

And where are they?

Alvise (31:57):

In all the [inaudible 00:32:00] Venice inside the lagoon, and then, there is lido, then, it is between the lagoon and the sea. You have these two holes that makes the sea comes into the lagoon. And in these two channels, they have been build this floating doors.

Sarah (32:20):

What are they made of?

Alvise (32:21):

Metal.

Sarah (32:22):

Metal.

Alvise (32:22):

Yeah. They get inflated, and they rise from the ground, underwater, and they comes up and close the channels to reduce the amount of water that comes inside the lagoon when the tide is high. They start using this MOSE right after the high tide of the 2019. To make it, they had to dig the ground under the sea. The MOSE works, but another problem is that it is very, very, very expensive to make it rise to close the channels, like hundreds, thousand of euros every time.

Sarah (33:04):

Well, coming back to your work, are there young artisans following in your footsteps in Venice?

Alvise (33:10):

Yes, and no. I’ll explain. Some of them are interested about this kind of work, but as I told you before, it takes a long time to understand how to do this work. And everybody wants to earn money quickly. They don’t want to wait to have the… When I began, it took me three years before I start earning something from this work. In the same time, I was fixing computers to live, to pay the rent, to pay my food and so on.

Sarah (34:02):

Taking on an apprentice is an expense for an artisan.

Alvise (34:06):

It’s very expensive.

Sarah (34:07):

To train someone is expensive.

Alvise (34:08):

Because if I have to make one job, one item, it takes me one week. If I took someone that works here, and I have to pay him to make the work, it took three weeks to make the same work. So, I spend more time for make one piece, and also, I have to pay somebody else. You can’t manage. It’s impossible.

Sarah (34:32):

If you were to encourage a young artisan, what would you say is the most enjoyable bit of the job for you? Because you obviously love it.

Alvise (34:39):

Everything. There is not one thing. We were talking about artisan, and just a few days ago with friends, you know, you don’t make the artisan, you are an artisan. It is just your way of living. When I close my workshop and I go at home, I’m still working, also, if I’m not here. It’s something you feel it. You just get relaxed if you think how to do for your work. It’s not something that makes you tired and you feel anxious, no. You feel relaxed. Just before sleeping, I’m just thinking, tomorrow, maybe I can do this for solve the problem on that item.

(35:33):

One thing to say that if you make your way on restoration, you can work and touch and understand masterpieces that the people normally can only see from distance. You can learn so much more than just seeing them.

Sarah (36:00):

So, thanks to Alvise Boccanegra. You can discover more about him from our website, materiallyspeaking.com, and see photos on Instagram.

(36:09):

If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, please, subscribe to our newsletter, so we can let you know when the next episode goes live.