Neil Ferber packing up at La Polveriera studios, 2019

Born in Wales, Neil Ferber started his creative life making models and objects in his parents’ garden shed. After art college he made his way to Italy with his wife, writer Kathleen Jones, where he discovered the artist community working in marble and based himself in several of the studios there. At the time of our interview he was packing-up from Studio La Polveriera in Pietrasanta and now mainly works in Cumbria at his Mill studios.

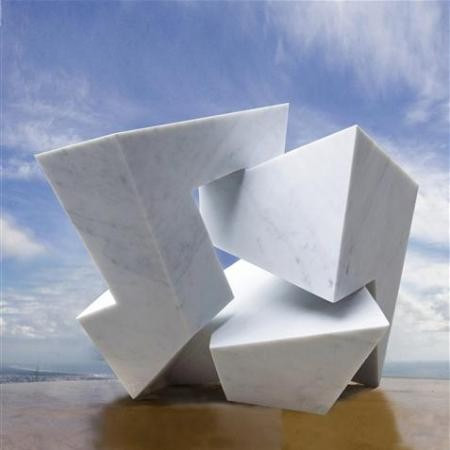

Neil's sculptures are abstract and often architectural or geometric in form, initially created in clay or wax before being cast in a variety of more permanent materials. He composes fully three-dimensional pieces where no one view dominates, all being of equal interest. Neil's work is held in private collections in Italy, Sweden, England and the USA.

Neil Ferber, Lock, marble, 40 × 40 × 42 cm

Neil Ferber, Split Sphere, marble, 42 × 38 × 38 cm

Neil Ferber, On Edge, Carrara marble, 47 × 49 × 43 cm

Neil Ferber, On Edge, steel

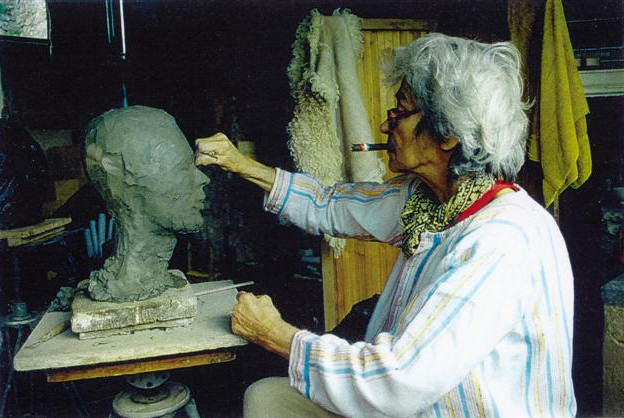

Neil speaks of his friendship with Italian-born Fiore de Henriquez in Peralta. She was sculptor to the famous, a flamboyant character and proud hermaphrodite who created portrait sculptures of John F Kennedy, Igor Stravinsky and the Queen Mother and is credited for introducing Cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz to Pietrasanta. In love with clay, a film of her life by Richard Whymark, tells more of her story.

Fiore de Henriquez. Photo: Kathleen Jones

Our interview took place in il CRO di Pietrasanta, an historic workers’ restaurant which has fed generations of artisans and remains a meeting place for artists. On the walls frames have been painted in which artists can sketch their contributions, while live music nights are a popular fixture here.

Library in il CRO di Pietrasanta

Il CRO di Pietrasanta. Photo: Il CRO di Pietrasanta

Links

Neil is a member of the Royal Society of Sculptors

This episode refers to Studio La Polveriera, now sadly closed with members having had to find alternative workspaces.

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound edit/design: Guy Dowsett

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Rose 1229/8, Gareth Johnson

Walking on the Cool Side 987/1, Paul Mottram

I have a sort of myself as a modeler. The creative bit is all in clay, you know, carving into marble and other things is just the way of making the work permanent. It seemed crazy to be here in this area. I’m not carved marble so I started to come down to Pietrasanta. When I came here everybody said no you shouldn’t have been here twenty years ago.

Neil Ferber:I work in five studios in Pietrasanta. Every one of the previous ones closed. I come with nothing usually.

Sarah Monk:Come with nothing?

Neil Ferber:Fiore was like a rock star where she went. She was larger than life and everywhere near her. So it would take half an hour just to do her 100 yards down the piazza. You know, their eyes would sparkle and they’d talk about art and I think, I want some of that.

Sarah Monk:Hi. This is Sarah with another episode of Materially Speaking, where artists tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today I’m meeting Neil Ferber, who was born in Wales and by his own account fell into art school and became a sculptor rather by chance. His journey to Italy also came about by happenstance, and he soon met one of the more flamboyant characters in Pietrasanta, Fiore de Henriquez. After her death, he was invited to set in her hamlet, Peralta, where he was artist in residence for six years.

Sarah Monk:I met with him at La Polviorera Studios in the center of Pietrasanta, formerly the historic Cervieti Studios. I’ve always loved the collection of traditional church figurines in the loft here, a historic reminder of the work done for churches and memorials made for personalities and politicians over many generations. The uncertainty of Brexit and likelihood that La Porvirera would be developed as apartments has triggered him to ship back his work while he can. He creates angular abstract pieces in white and gray vein marble. I see them carefully crated up and piled on a small forklift waiting to be transported.

Sarah Monk:We head around the corner to Ilcrow Di Porta Aluca, a historic workers’ restaurant. Here, they kindly let us use their library, complete with old fashioned gramophone and horn. This seems strangely appropriate, as I know Neil’s wife is a writer and that he is a keen jazz fan.

Neil Ferber:My name is Neil Ferber. I’m an English sculptor working some of the time in Pietrasanta.

Sarah Monk:Let’s start at the beginning. Where were you born? And can you tell me a little about your childhood?

Neil Ferber:I was born in South Wales, spent the first eighteen years of my life in South Wales. And then I left home, learned sculpture in a college in Reading, Three Years teaching in a country school, which gave me plenty of time to carry on making sculpture.

Sarah Monk:So you worked in how many mediums when you were young?

Neil Ferber:I mean in a way I’ve only ever worked in one medium which is clay, but clay doesn’t survive. You can’t just put it on the shelf. There’s always been a problem of making it permanent. And for a long time in England the only way I could afford of doing this was to cast in resins and concrete. I never had the money to get bronzes made, which I would have liked at the time.

Neil Ferber:I didn’t carve at all. I never thought of myself as a carver. Well, Tutu used to say, you know, sculptors are either carvers or modelers. I always thought of myself as a modeler. It’s like the creative bit is all in clay, you know, carving into marble and other things is just a way of making the work permanent.

Neil Ferber:And I bought a huge water mill, which I still have and it’s still my home in England. I moved north to the Lake District, or just outside the Lake District. Bought it for very little money and I had tons of space to work. And until I found Pietrasanta, I worked there. I had a gallery and a studio, a potter, a ceramicist.

Sarah Monk:Painting.

Neil Ferber:I went to a teacher’s training college where my staff had just all left Leeds Art College to run an art department in this progressive teacher’s training college. My mother decided, she got me some forms and said I should go and do this teachers training college because I was not knowing what I was doing in my life So thought to pleaser I filled in the forms thinking nothing of it and I got an interview and because I filled in the forms wrong I got an interview for the art department I had one painting I’d done previously on my own. Went and I was lucky the person running it was ex head of Fine Art of Leeds. He was looking for people who weren’t the normal A level art sort of people. And I must have said something right, you know, because I got on really well with him, and I got a place, and I thought that I’m gonna be found out here.

Neil Ferber:You know, I can’t draw, you know, I’m not an art person. I did O level art, about it, you know. I’m surrounded by all these clever people who can draw and do all these smart things, right. But luckily, because they wanted to break away from the traditional sort of thing, they started the whole course with sculpture. And my father was a carpenter, I made things in my shed all my life since I was small with his tools and wood.

Neil Ferber:So making things by hand and the exercises I gave us came natural to me really and that’s why I got into sculpture at the age of 21, 20 maybe, at college. The people running the course, they were the first adults I’d met, you know, after leaving school or everything. First adults I met were passionate about something. You know, their eyes would sparkle and they’d talk about art, and I’d think, I want some of that, you know? And so I learned a lot from these people because they took art seriously.

Neil Ferber:And so I spent three years in this college and when I left that I just wanted to carry on. My wife’s a writer. A writer friend of hers said, If you want somewhere to go and rent cheap in the winter just to write, I go to a lovely place, Peralta in Kamehore in Tuscany. So she booked a couple of weeks and we came and just by chance John Marsh, who was a pre Raphaelite scholar and writer, was writing a biography of Fiore de Henriques, who lived at her altar, the most interesting person. And both my wife and her had written books on Christina Rossetti, so they knew each other.

Neil Ferber:And just by chance she was there at the time, so they got to meet Fiore and Diana, her partner. And one thing led to another, next year they came back from war. I did their website and I got to know Fiore better. So I started coming more and more to Italy and staying with Fiore.

Sarah Monk:I’m afraid I don’t know about Fiore. Can you tell me about her?

Neil Ferber:Oh Fiore, where do you start? Fiore was born in 1920. Studied sculpture. She came and lived, I think in Cazoli First with a sculptor called Morabita, was quite a well known Italian sculptor at that time. And she was hermaphrodite so we never quite knew Emine I always thought of her as being a woman but she wore men’s clothes and was very androgynous and very beautiful when she was younger and controversial.

Neil Ferber:I don’t know to start with Fiore, she’s an Italian sculptor from Trieste. It was a period in the 50s and early 60s where she was a flavour of a decade in London doing portraits of all the people like Shirley Bassey, even the Queen Mother. She’s very prolific reporter and very good at portraiture. She spent time in America doing lecture tours. She met Lipchitz and convinced Lipchitz the best place for the foundry and to have his work cast would be in Pietrasanta so she brought Lipchitz over who ended up buying a big house just outside Cameoli called Villa Bosea with his wife Ulla and they were all three very friendly for quite a while, but I’ve never really got to the bottom of all the stories around her and Lipchitz, but finally they fell out and Lipchitz threw it out in the middle of the night.

Neil Ferber:And just above his house in Pietrasanta, there was a derelict little hamlet called Peralta, which she bought, and then dedicated the next twenty years of her life to doing it up, bit by bit buying other hats, just collecting with a hamlet, and was a local celebrity. Larger than life, if you ever met her, you wouldn’t forget. First brought me to Pietrasanta, that’s an interesting story. Pioli was like a rock star where she went, she was larger than life and everywhere knew her, so it would take half an hour just to do her 100 yards down the piazza. What impressed me was she took me down a side street in Piazza and into a shop that looked a bit like a mini mart.

Neil Ferber:And I looked in and every single thing in that mini mart was to do a sculpture. Every tool, chisel or anything that could do a sculpture you could buy. There was a whole shop in a town that was just selling things to do with sculpture. Well, that’s not possible. In England we have one.

Neil Ferber:We have Taranti, a tiny little place in the back street in London. Again, by an Italian. So I was incredibly impressed with this place and I began to realise that Pietrasanta was full of sculptors and it was a sculptor’s town. I got to know her in Peralta and unfortunately five years or so after she died she went through Alzheimer’s and died. But I was by then quite friendly with Dinah who was her partner and it wasn’t until she died, but I started to actually make sculpture at Peralta.

Neil Ferber:But I didn’t tell Fiona I was a sculptor for ages. Yeah, so Dinah let me have a studio there, and I built a studio in Metaller there, and I worked there for, I called them at least six, seven, eight years, And initially I wasn’t carving in marble. I’d never carved marble, but it seemed crazy to be here in this area and not carve marble. So I started to come down to Pietrasanta from Peralta and carve some of my pieces into marble and that moved on to me renting a house above Pietrasanta for six years where I have a clay studio up there and I’ve worked in five studios in Pietrasanta every one of the previous ones closed so I’m still in that situation now with Paul Vieira, the last one and that looks like it’s going to close so that’s a sad thing when I came I was worried about getting a place in the studio they were all so busy you know and now there’s only two left that are actually working in marble. That’s a great shame.

Sarah Monk:So am I right? Do you work primarily in clay? And then what’s your process of working?

Neil Ferber:It usually takes the longest time really pushing clay around until I find something that I think is tight enough and has something about it. Then I make a waste mold, which means I just have to get it apart so you can take out the clay so you then have the sculpture in negative bits of plaster and you put it back together again with mould. For me, I fill it again with plaster, sometimes a slightly harder plaster. And then, when it’s called a waste mould, you waste it, you break off the mould and you’re left with a plaster copy of what was in clay. The plaster then needs to dry and then it can be refined.

Neil Ferber:It’s not easy getting smooth surfaces and sharp edges on clay, but once it’s in plaster you can get it very, very exact. If there are a lot of round complicated sort of surfaces, I would copy one to one using the pointing machine. If there were more angular and flat planes, I would just make them by drawing and cutting card pieces and measuring, and often double or trebler size. So that’s the sort of process. I mean, it’s the process of old sculptor.

Neil Ferber:In Renaissance times, they made clay or wax models, then they made plaster models, and then they refined them, and then they carved them.

Sarah Monk:So the pointing process

Neil Ferber:It is foolproof if you’re very precise, and you make sure that you tighten everything as you should every single time. But when you’re taking points, I mean, on a complicated piece, you take hundreds of points, and you’ve only got to forget to tighten one little bit on the machine and it moves when you transform it and you can ruin a piece. I find it quite nerve wracking. It doesn’t interest me to sort of start with a piece of stone and then see what happens. I think I started when the size of this room might end up with something the size of a matchbox because it’s very hard to visualise when you do something on one plane what it’s going to look like when you go round.

Neil Ferber:Clay is brilliant for that because you can continually turn a piece in clay and try, and then if you don’t like what it does, you put it back again. You can’t do that in marble. When I carve in marble, I do want an exact copy of what I’ve done. I don’t want to invent anything new. I’ve done all that.

Neil Ferber:It’s just a way of making what I do into a permanent material. And that is sellable. I cast a lot in resins back in England, but as soon as we tell people they’re plastic, they’re not interested.

Sarah Monk:Has that changed over the years?

Neil Ferber:No, it hasn’t been anyway, no. Bronze and marble are romantic materials that people will invest in. Steel, not so much. And recently I’ve been working lion’s steels.

Sarah Monk:How’s the process for choosing marble?

Neil Ferber:Statuarty is good certainly for the roundish ones that I have. I don’t like a lot of fussy colour and things going on because it works against the forms. I look quite like some of the grey. We’ve done a couple in Bardiglio. I’m not really into stone for stone’s sake, it’s a sculpture that interests me.

Neil Ferber:There’s a lot of people who come here and they make the same sculpture over and over again in different colored marbles. It’s more about stone than it is about sculpture. So I like to make the marble do all I want to do, not like accidents.

Sarah Monk:And what about bronze? What’s the appeal of turning one of your clay pieces into a bronze?

Neil Ferber:Some of them do suit bronze, but certainly the smaller ones that I’ve got. And it’s very precise. But finishing in the bronzes I did myself, because there is a danger that they’re not done accurately enough. If my work depends on flat planes and sharp edges, you know, it’s just my sensibilities like that. And so if I have a sharp edge where have two planes of me, it’s got to be sharp, it’s got to be exact.

Neil Ferber:Yeah, can achieve that with bronze.

Sarah Monk:How does the three dimensionality play out for you? Do you have a front and a back?

Neil Ferber:How’s No, no, that’s a good question. I think a lot lot of sculpture these days is two dimensional. For me, I mean, my love of sculpture comes from Giambologna and Michelangelo, you know? Complex figures when you move around, every line turns into another line, and there is absolutely no front and back. You know, I’d like 60 degree views so that they do work as you walk around I don’t find any way of doing that other than with clay It’s hard to do if you start it in marble I mean it’s a very sophisticated thing to do A lot of ancient sculpture, you know, like Egyptians sculpture, was just meant to be viewed from one place.

Neil Ferber:It’s only when the Greeks and then the nation sculptors started making these fully round sculptures, you know, and it’s a very sophisticated thing to do, but very difficult. So I’m I’m only feeling now that I’m just starting to be able to make pieces, some of which even work when I turn them upside down. And it’s taken a lifetime together, and I wish now I had another twenty or thirty years of power.

Sarah Monk:Can you speak a bit about what typifies your work?

Neil Ferber:The back of my student base. I’m not actually doing anything different now fifty years later. I’m still using the same language. And it is a language and it’s about learning a language and working the same language over and over and a lot more of what you do becomes instinctual you know in a way that when you learn to drive a car you have to think about everything you know Those processes become unconscious I go through loads of ideas when I’m working on clay and then I have to check them out if they don’t work in that piece But I never lose them, they’re part of a learning process and building an instinctual library of form yeah you have a much wider range to call on the more you do it I didn’t sell any sculpture for years, twenty or thirty years I didn’t ever feel it was good I was a bit naive at all, my point is good enough it can set itself but that’s not actually true stuff I’ve done since I’ve been in Pietrasanta in the last few years things have moved forward and my sculpture is better and it’s nice to enjoy compliments from other sculptors that are here.

Neil Ferber:Yeah. Helps keep you at it.

Sarah Monk:So you seem to have come to Pietrasanta by chance perhaps.

Neil Ferber:Yeah. Mostly by chance.

Sarah Monk:What do you think makes such a strong artistic community here?

Neil Ferber:It’s getting weaker all the time, unfortunately. But yes, you know, when I came here, everybody said that he shouldn’t have been here twenty years ago after a fact. In the nearly twenty years I’ve been here, has suddenly declined. The number of sculptors, number of artisanis, the number of workshops, everything has diminished. It’s a mixture of all these things, of studios and the easy availability of stone and foundry work, and the fact you meet sculptors from all over the world.

Neil Ferber:Whereas in England, I live in the middle of nowhere, in a small market town, 300 miles from London, and I don’t really know anybody. To have any measure of success and sell in England, you have to live in London. You have to be known and seen on the scene. And I live in a very remote If I go to sit in a local pub, I talk to farmers they don’t talk to the sculptors who you know they might be interested in talking about the hay yield but they’re not good on sculpture I do feel you know I mean it was a good move to move North Of England because I have a large property with studio space and everything and everybody I know as a sculptor in London, I mean every square inch is valuable and studio space is incredibly difficult. But then you know you’re also seen as provincial if you don’t live the city.

Sarah Monk:And what about the political situation? Has that impacted? Well,

Neil Ferber:only that I don’t know what’s happening. So if I’ve got to move all my stuff and use a shipping company, I just know if a no deal Brexit does happen, that’s gonna cost me more, you know, and be more difficult paper wise. If the studio hadn’t been under threat of closing at the moment, I would have probably waited. But just seems like it’s imminent now. And who knows what the situation is gonna be in six months’ time.

Neil Ferber:My friends in Pietrasanta are either Norwegian or Dutch. I think they feel the same, they like being here to talk and socialise alone. They rarely actually talk about sculpture, but it’s nice people sit around in them. They’re all very individual people, the people that come here. There’s a lot of very single layer female sculptors without a relationship that over the years come with.

Neil Ferber:Very strong minded sort of people and they’re very interesting, you know. So he makes some very nice friends.

Sarah Monk:Thanks to Neil Ferber. Since this recording, Neil has had a productive year in his studios in a converted mill in Cumbria, but he’ll be back in Pietrasanta as soon as he can travel. You can see his work on Instagram, @neil_ferber, or on his website, neilferber.co.uk. And thanks to you for listening. As with all episodes, you can find photographs of the work discussed on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, or on Instagram.

Sarah Monk:If you’re enjoying Materially Speaking, please subscribe to our newsletter, so we can send you news and let you know when the next episode goes live. And if you feel moved to leave a rating or review on your favorite podcast platform, we’ll be delighted as that will help people find us. In our next episode, I’ll be talking to a young Dutch artist Badriah Hamelink, who after recently facing a near death experience has doubled her determination to focus on art.

Badriah Hamelink:The first thing that really came to mind after this had happened was, wow, I’m still here. I can be here. With that comes a certain determination, I think. I went hiking in Garfanjana and I saw all these incredible rock formations. And there was this power, this absolute power of the universe.

Badriah Hamelink:The power that pressed everything together and made mountains rise up. There’s something very fascinating about that to me.

Sarah Monk:Listen out for Badriah Hamelink Absolute Power.