Cynthia Sah in her studio

Cynthia Sah was born in Hong Kong and studied in the USA. She first came to Italy in 1978 to study and came back soon after to learn with the artisans. She has stayed ever since and now works in a studio complex with her partner, Nicolas Bertoux.

Inspired by the form, movement and colours that nature gives us, Cynthia tells how she always looks for the spine in a piece. She loves how the energy of a wave – of water, sound or wind – reminds her that we are all connected.

Cynthia Sah, Fern, 2019

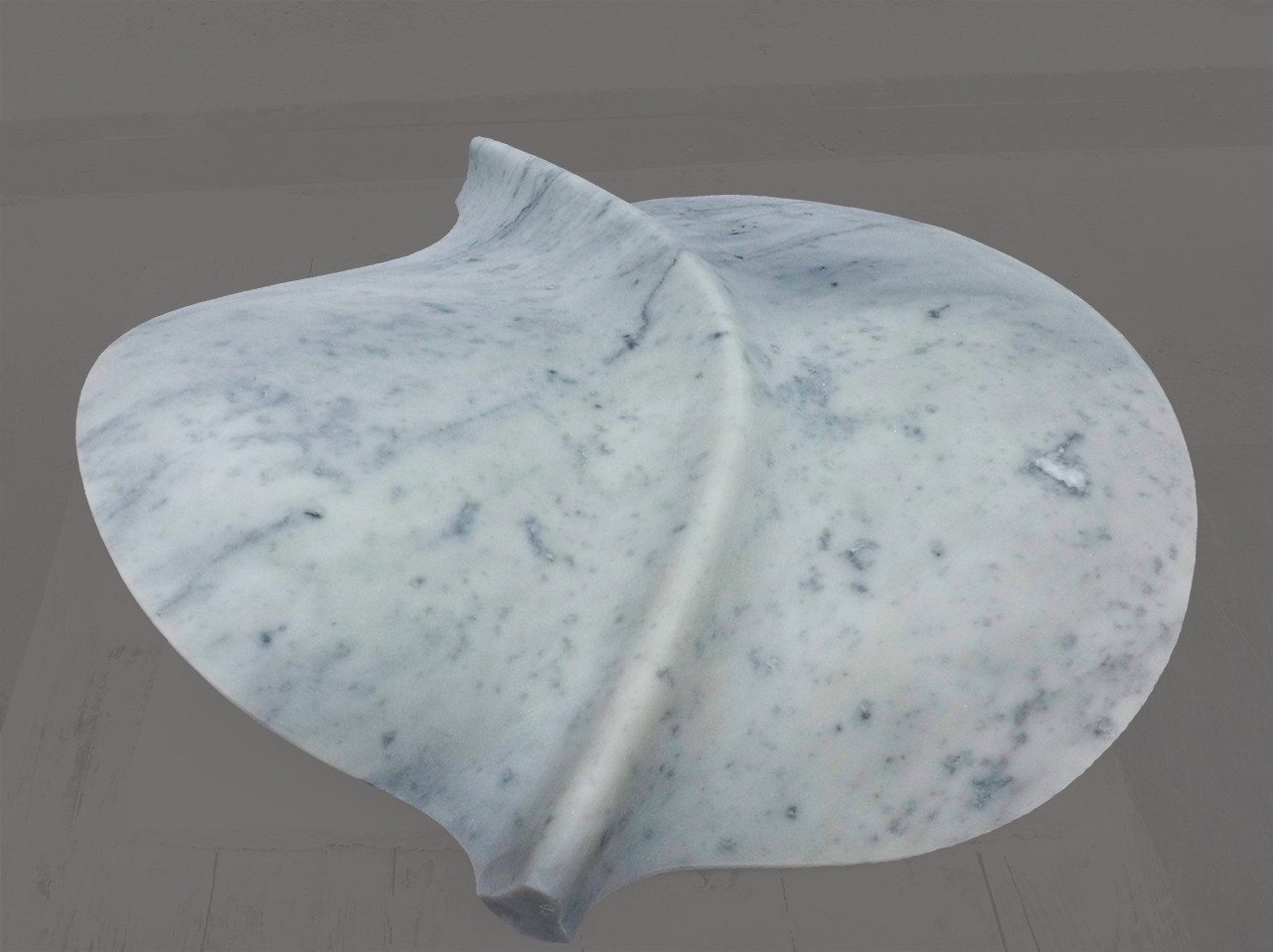

Cynthia Sah, Stingray, 2020

Cynthia Sah, Wave, 2020

Gallery spaces being altogether different to her studio environment, Cynthia prefers to settle her pieces into their new home personally. But lockdown entailed her having to learn to curate a show long-distance this year. Here she describes the process.

Cynthia Sah, Balance & Counterbalance, 2000, arabescato white marble, 2 × 7 × 2 m, Taipei, Taiwan

Cynthia creates public art for all over the world. She talks about a special commission she did for a grieving daughter in memory of her father, called Balance & Counterbalance.

Underpinning her public art is the idea that sculptures should be friendly and invite you to touch or sit on them.

Cynthia Sah and Nicolas Bertoux, Aquarium, 2012, white marble, 10.4 × 4.5 × 0.24 m, Taipei, Taiwan

Finally Cynthia takes me to their basement, and what was originally a trout farm feeding the Medicis in the Palace opposite. This breathtaking long gallery is now their exhibition space, where they host events for their non-profit foundation, Arkad.

The gallery in Cynthia and Nicolas's workspace, Seravezza

Credits

Producer: Sarah Monk

Sound edit/design: Guy Dowsett

Music: courtesy of Audio Network

Nature Of Winter 2 3238/66, Richard Lacy and John Ashton Thomas

Fifth Dimension 2 3253/34, Jody Jenkins

Seeking 3088/8, Mark Johns

All photos by Cynthia Sah

Marble is alive. It has a lot of grain and hard parts, soft parts and surprises. So it’s a lot of fun to work. But it has a life. To work in stone is not beating it up.

Cynthia Sah:Caress it. Stone, any kind of material in nature is a gift from nature. So we have to take care of it. Art should be part of your life. We are all connected.

Cynthia Sah:Everything is connected.

Sarah Monk:Of Materially Speaking, where artists tell their stories through the materials they choose. Today, I’m meeting Cynthia Sah, who came to Italy in 1979 and now works in a studio complex with her partner, Nicholas Berto. As I drive through Serevezza, I come face to face with a handsome cream colored palace with a fine strip of green lawn in front of it and the towering Apuan Alps behind. Cosimo de Medici the first, grand duke of Tuscany, built this residence in the 1560s during his visits to the mines and quarries of the region. He was keen to profit from the valuable marble, iron and silver resources here.

Sarah Monk:On the left of the palace, next to the river, is a long low building with arched windows, and this is where I meet Cynthia. The larger part of the complex is a historic sawmill, now a vibrant workspace using state of the art technology and producing monumental sculptures. In the smaller part are offices and meeting rooms, and it’s there that I catch up with Cynthia and hear about her smaller works, inspired by nature. Then she takes me to their basement, and what was originally a trout farm feeding the Medicis in the palace opposite. This breathtaking long gallery is now their exhibition space, where they host events for their non profit foundation, RCAD.

Sarah Monk:Finally, Cynthia takes me inside the workshop and you can hear the roar of machines as larger pieces are brought to life. Many of them public art, heading out all over the world.

Cynthia Sah:My name is Cynthia Sah. My Chinese name is Satan Lu.

Sarah Monk:Can you describe your work a little on how it’s changed over the years?

Cynthia Sah:One thing I learned for a marble piece to stand safely and securely, you need a spine. Some of my pieces are very thin. One piece that I call fern, because it’s like the tip of the fern, it has the spine that curls into a circular movement. And everything has a spine, even if you look at the form of a leaf or form of a petal. They all have a spine, an inner structure that keeps them together.

Cynthia Sah:For me, a sculpture should also have a spine. And if it doesn’t have that inner structure, it would be floppy, floppy, sloppy. It will not stand as beautiful petal. A petal is very thin, very delicate, but it holds up. That is actually one of my very important direction, is always looking for a spine in a sculpture.

Cynthia Sah:Whatever I’m inspired by, even movement of a wave, I do a lot of movement of the wave. And that energy, energy of a wave that bring you up and down, if we want to call it the spine, that energy that connects the movement. Without it, you would be falling apart, it would be going just everywhere. It could be a sound wave or a wave in the sea or a wind that produced a wave. It is also connecting all of us.

Cynthia Sah:We don’t see it, we feel it, but it could be coming from North Pole or China or it could be bringing very fine sand from very far away and touches you. We are all connected. Everything is connected. If I talk about my work generally, a lot of work is inspired by nature. When I observe nature, images come to me in that gratefulness.

Cynthia Sah:I felt very grateful that nature gave us so much form, so much color, so much movement. All of that inspires me to make this form. Whenever I look for form or line, I get more and more essential, simple, and yet it’s not simple. Because when you have a very essential form, the form and the movement and the line is even harder to grasp because it will be more obvious when it’s wrong. The movement has to be continuous because we are working three dimensions.

Cynthia Sah:So, when you look at a piece, you have to imagine what’s in the back.

Neil Ferber:When you move just a little bit, does it continue, the form, or it has stopped? You have to work three sixty degrees all the time, moving it, moving it until it’s all harmonious in all forms, almost like you have found it in the river stone in very little intervention.

Cynthia Sah:Two more recent sculptures I made inspired by stingrays. I love their movement, their wing, almost like a wing. And when they swim, it’s almost circular. They’re able to move around so gracefully. Bringing out the most beautiful part of nature because nature could be rough, could be destructive, but I wanted to bring out the beauty.

Cynthia Sah:Human being, us, we sometimes destroy it without looking carefully. Nature speaks to us. I work in marble, even stone, it seems hard. But it has an inner life and we have to bring that out. I always say stone, any kind of material in nature is a gift, so we have to take care of it, caress it and become your second skin, so to speak.

Cynthia Sah:That’s my direction. I was born in Hong Kong. We lived in Taiwan and Japan. And when I was 18, I went to The United States to study. I came here to Pietrasanta in 1978.

Cynthia Sah:With Columbia University Teachers College, there was a sculpture course, and we came here for one month, and I decided I have to come back to be with the craftsman and learn the craft as well as I can. I felt there was a lot to learn here, not only technique, but how to treat marble. The craftsman also taught me the philosophy of how to respect marble when you work on it, how to appreciate it. Petrasanta at that point was like a small village. Lots of young artists and older artists and famous artists, we were all together.

Cynthia Sah:There was no division of, You’re well known and I’m young and not well known. And everybody worked together, and there was an exchange, a human exchange. And so I have met Isamu Noguchi here, and he’s my hero. And I was trembling when I met him, but he was so human,

Cynthia Sah:he made me comfortable, very comfortable. I even cooked for him. I would never think of it if I was in New York to do that. I love being in New York, but New York is like a wild wild west for artists and was too confusing and too distant for me. It’s not the kind of artist life that I wanted to live.

Cynthia Sah:I always wanted to do drawing and handwork using my hand, but my parents said they don’t agree because I’ll die from starvation being an artist. They convinced me to do something else. So to please them, I studied psychology. I wanted to know more about what our spirit, our soul, how it works, and what makes us normal or not normal. After four years studying psychology, I decided that they didn’t have the answer.

Cynthia Sah:So, Okay, at this point, better do art because there’s no answer to that. That’s where I found my passion. When I went to teachers’ college, my first course in sculpture, they gave me a piece of marble to carve. And I started to carve, and I could never put it down again. There was love for the stone.

Cynthia Sah:I felt differently. I did some clay, ceramic. I tried everything, but there was not that contact I had with the stone. The Chinese culture, we loved to look at nature, we loved to collect stone, you know, sometimes see a piece of stone and it looks like a landscape. You know, if you go to a Chinese museum, ancient collection, you could see a piece of meat inside of stone.

Cynthia Sah:Chinese like to make stories when they collect stone, what they see inside the stone. When I lived in Japan, when I was five to 11 years old, I was very much alone because there was a big separation between Japanese and Chinese. So, I grew up with very few friends. But I spent a lot of time in this Japanese garden in our yard. Somehow, it really left me this image of a Japanese garden, the balance, the harmony, the use of stone.

Cynthia Sah:Unknowingly, it was aesthetically very influential to use in my future creative process. I believe that whatever your experience, and sometimes unconscious, sometimes cultural influence that you didn’t even know or you even try to reject, It’s part of the ingredient in your creativity, and I’m very grateful for that. With the age, maybe, the oriental way that I see things, it’s coming out more and more now. Before, it was maybe more Western modern art that influenced me. But I see that my language is slowly going back to the oriental spirit, I would say.

Sarah Monk:I know you do a lot of commissions, but do you like to know where your pieces are going or do you work more towards gallery exhibitions?

Cynthia Sah:Nicolas has taught me a lot of things about space. While I still don’t have a lot of capacity of imagining the sculpture in a space, when he looks at a plan, he can imagine the space. He can imagine the sculpture in the space. I’m usually more interested in smaller work because it’s small. I can move it around and I could look at it in many ways.

Cynthia Sah:And so to imagine it huge, more than three meters, it’s very, very difficult for me. I have an assistant, a robot do the roughing out, so I can more concentrate on finishing or the feel of the sculpture itself. The feel of marble for me is very important. It’s different from metal. Metal is very consistent.

Cynthia Sah:And to me, marble is alive. It has a lot of grain and hard part, soft part, and surprises that sometimes you don’t need. But it has a life, so it’s a lot of fun to work in Marble. At the moment, a lot of commissions are from Asia, China, Hong Kong, mostly in Taiwan, because we have a very good agent there. We have established our position there and very appreciated there.

Cynthia Sah:In February, I was approached by a developer in Taiwan, and she just took over from her father, very young. And she wanted to make a monument for her father. But she was very wise to say that, Well, I don’t want a figure, but it could be just a sculpture that could represent the memory of her father. So I made this sculpture that’s called Balance and Counterbalance. The sculpture was more horizontal, six meters long, and her buildings are always very, very high.

Cynthia Sah:I cannot reach that kind of height. In that way, human, it’s short, people can go around it, and it’s not aggressive. It’s two wings. People can go underneath, sit on it. For me, that represented the ideal of what sculpture should be for people to touch and even sit on it, not aggressive, but it’s fluid, it’s friendly.

Cynthia Sah:Our philosophy is that public art has to be friendly, not dangerous, but inviting people to touch and become a symbol. When they come to the area, they remember that sculpture because it’s friendly to people.

Sarah Monk:Gosh, it’s gorgeous. Long arched hall. Beautiful.

Cynthia Sah:Every year, usually we have an exhibition.

Cynthia Sah:Mhmm. This year, we won’t because we’re working on presentation on our foundation. We need more support. We’re working on the future of the foundation. This is maybe 80% of last year’s exhibition.

Cynthia Sah:There’s a lot of different opinions. Some of it is like we are destroying nature. Some people hate to look at marble quarry. We’re trying to say that, yes, sometimes it seems like we are destroying nature, and yet there’s the other side. With marble, we have created beautiful artworks in ancient times, buildings and churches.

Cynthia Sah:Of course, we have to be conscientious what we do, try to appreciate and make use of the marble as well as we can without destroying it. But with the new technology, like I said, you can cut out the outline of a sculpture and you can use the other for something else.

Sarah Monk:So all the offcuts are being used. Nothing’s wasted.

Cynthia Sah:You can do a lot more with a machine now than when you didn’t have it before. You can save a lot more marble.

Cynthia Sah:I usually make a model. From the model, sometimes make into three d. Three d is good to have for longer process. Mhmm. Because you can make it bigger, you could adjust it.

Cynthia Sah:When you do it in clay, plasticine or whatever, you cannot really move it. In three d you can change. From the model it’s an initial idea. Our technician makes it into three d. Then there I can make it rounder or thicker.

Cynthia Sah:It’s easier to do. With the clay, it’s more difficult to control. In any case, once we have three d and when it’s ready, we send it to the factory that has computerized machine or robot that rough out for us.

Cynthia Sah:Sometimes we ask a system to rough out for us.

Sarah Monk:Yes. Depends on the job.

Cynthia Sah:If technology taking over, there are no more craftsmen, it’s true anyway. I don’t know if it’s because there’s more technology. If we want to find a good carver, a craftsman, it’s very, very hard. Very hard to find.

Sarah Monk:So the young people aren’t training as such or too much demand for them or they’re

Cynthia Sah:just not getting enough? No young people learning the craft. It’s been like that over twenty years. Very soon there won’t be none. And there are just a few, maybe Studio Sam, they try to train the young ones.

Cynthia Sah:Some studios have remained, but who wants to take time to be good after 10:20 years? Whereas young people are not that patient. And there’s not a lot of future either. It used to be a lot of craftsmen were making church figures, and there’s not a lot of work from church. In general, even in contemporary art, marble is not being used.

Cynthia Sah:Abstract or figurative, there aren’t that many artists make sculpture in marble. It’s conceptual. Everything is conceptual. Concept is more important than actually making it. And so we don’t mind not being considered contemporary artists, except that we’re still alive.

Cynthia Sah:Very often we’re asked, Are we contemporary artists? Because we’re not making video, our work is not conceptual in a way it will last a long time, hopefully. This material, marble or stone or bronze or metal, you don’t really see represented in, let’s say, international biennial works. When this was built, they were using water to run the machine. They had a canal that made the river run through here in the studio and the water came down, moving the wheels.

Cynthia Sah:There were transmission here. The water made the wheels turn and the wheels made all the other wheels turn and brought the movement upstairs where they were cutting machines.

Sarah Monk:Okay. So it was a mill driven cutting machine? Yes. Gosh, that’s beautiful.

Cynthia Sah:It was the first bubble cutting factory using the machine, maybe the first one in the world. Wow. This year. Yeah. In the 50s, they used electricity to run the factory.

Cynthia Sah:It can go into the river from here.

Sarah Monk:Are there any fish in it?

Cynthia Sah:Yes, plenty. Medici family used to have a trout farm here. Of course, it was not covered. It was just a pond. There’s a sketch from the gallery.

Sarah Monk:Gorgeous and cool. It’s an amazing building, really amazing. So when did you come to it?

Cynthia Sah:We bought it in 1999. Mhmm. And gradually made the restoration. It was run down very precarious, unsafe. But this, we restored right away because we had funds from the EU because this area needs to be supported.

Cynthia Sah:They gave us half what we need to restore this place to make it a showroom. It’s actually for craftsman artisan to make a showroom. And so we used that money to do the restoration here. Even though upstairs was very urgent to do, since we can only do this, we just say, okay, we just take the money and restore the gallery. People start coming and realize what the gorgeous space it is.

Cynthia Sah:It’s not finished. Still a lot to do, but at least we can live safely.

Sarah Monk:It’s an amazing project.

Cynthia Sah:We’re not business minded. We don’t know how to look for the funding. We’re still looking for someone who can do it for us. The dream is that it will continue after we’re gone, continue to be a creative, productive place where artists can experiment, create, work here, and stay here. A dream studio.

Cynthia Sah:We already have the gallery. Whatever is created here can be shown in the gallery. It’s a lively place. We’re older. We’re in our sixties.

Cynthia Sah:60 seven now.

Sarah Monk:Can I speak for yourself?

Cynthia Sah:Yes.

Sarah Monk:I’m only 66 now.

Cynthia Sah:We still want to be creative. We still want to experiment. And that’s the, I think, the spirit of all artists, is that still there’s so many fresh ideas that you haven’t realised. We want to give that opportunity to other artists when we’re gone. Well, still when we’re here.

Sarah Monk:Nicholas talked about being in Hong Kong with your exhibition during the crisis and also that you had a piece going to Wuhan just at the beginning.

Cynthia Sah:Sent off a lot of sculptures in February and another four sculptures in March. This was for an exhibition in Taipei. Of course, before the lockdown, we were planning to go. And I had to explain the work to people, gallery and curators, what they’re about. How you set up the sculpture is very important for an exhibition.

Cynthia Sah:Usually, the artists have a certain direction or vision of how they want the sculpture seen in the exhibition. Exhibition space is usually very impersonal. It’s a room and it’s different from when you’re working on it in your studio. It’s intimate and there’s a process going on, energy going on, but all of a sudden it’s finished and you bring it to another space that’s totally foreign to the creation of the sculpture. We usually like to be there, to cocolare, I don’t know, so see, caress the piece and say, You’re going to be okay.

Cynthia Sah:This is your new home, to make it fit into a foreign space to the sculpture. So the fact that we couldn’t be there, I had to explain to the curator who was going to present the exhibition to the public, the whole story behind almost each piece. And I started to do that. For lockdown, what we miss the most is to be able to hug our friends.

Sarah Monk:Yeah, I think I miss that the most too. There were phases of being productive and being self sufficient and everybody was in the same boat but that human touch and I still find it odd not to be able to greet people with a hug or say goodbye with a hug. It’s very strange.

Cynthia Sah:I realized that since we have the mask, the expression of your eyes are very important. And I look more in the eyes of people, and you try to express more through your eyes because sometimes you just don’t see. But then I see that they’re smirking or it’s very expressive, or smiling, or really greeting you, or saying goodbye. In that way, we’re more careful, more observant. It will change our lives.

Cynthia Sah:Since I’m Chinese, we don’t really hug or kiss, really. When we meet friends, even close friends, we are able to show respect without touching, let’s say. And now I’m used to the Western way of shaking hands and kiss both cheeks. And sometimes you don’t even know the person, you kiss them both cheeks. And that was a little difficult for me in the beginning when I came to Europe.

Cynthia Sah:But now that I’m used to it, I do it. So almost automatic, I want to give somebody a kiss on the cheek or affection or friendliness or openness to shake hands. Art should be part of your life and not only in the museum or anyone who can collect it. I hope that it’s become a friend. This piece is a friend.

Cynthia Sah:I gave something to this artwork, maybe a friendship or maybe affection, and whoever collects it is getting that kind of emotion from me. And I hope that is the connection of the sculpture, of the artwork to the person who’s buying or adopting it.

Sarah Monk:Thanks to Cynthia Sah. You can see her work on her Instagram, @chaneucynthia, or on her website, cynthiasah.it, where you can also find out more about the RCAD Foundation. And thanks to you for listening. As with all episodes, you can find photographs of the work discussed on our website, materiallyspeaking.com, or on Instagram. If you’re enjoying materially speaking, subscribe to our newsletter on our website so we can send you news and let you know when the next episode goes live.

Sarah Monk:And if you feel moved to leave a rating or review on your favorite podcast platform, that would be great, as that will help people find us. In our next episode, I’ll be talking to Neil Ferber, who was born in South Wales and started making models in his parents’ garden shed.

Neil Ferber:Carve as a model is I always thought of myself as a model. It’s like The creative bit is all in clay. Carving into marble and things is just the way of making the work permanent. It seemed crazy to be here in this area. I’m not carved marble so I started to come down to Pietrasanta.

Neil Ferber:I’m really feeling now that I’m just starting to be able to make pieces, know, some of which even work when I turn them upside down. And it’s taken a lifetime to get there.